Mortimer is a bright but somewhat gormless young man who is all elbows and knees. His father is desperate to find him a situation and thus send him on his way into the world. So, on Hogswatch Eve they go into the village of Sheepridge, along with all the other fathers and their likely young men, to get set up with an apprenticeship. As the day goes on, the crowd of young men thins, but Mort remains un-apprenticed. As midnight looms and Mort remains the only young man standing in the village common, and his father says disappointed but encouraging things, a tall skeletal stranger approaches. There is something odd about him, not least that he’s literally skeletal: Mort “found himself grabbing hold of a hand that was nothing more than polished bone, smooth and rather yellowed like an old billiard ball” (21). The stranger’s hood falls back, “and a naked skull turned its empty eyesockets toward him.” Mort is oddly unfazed. “Excuse me, sir,” he says, “but are you Death?” (22).

Indeed, it is in fact Death himself, the Grim Reaper, the Stealer of Souls, Defeater of Empires, Swallower of Oceans, Thief of Years, The Ultimate Reality, Harvester of Mankind1 …

You get the idea. Anyway, Death is in the market for an apprentice. Why Death wants an apprentice is unclear at first, but it turns out Mort isn’t the first mortal he’s taken on. Mort soon meets Albert, a former wizard of some note who now acts as Death’s manservant, and Death’s adopted daughter Ysabell—with whom Mort forms a prickly and combative relationship of the entirely predictable variety.

Why does Death, who self-identifies as an anthropomorphic personification, want or need an apprentice? As it turns out, he wants to take some personal time; he wants to satisfy his curiosity about these weird and feckless mortals for whom he acts as psychopomp2 by spending time among them. This motivation only becomes apparent as the novel progresses, however, so as Mort awkwardly takes on his new employer’s robe and scythes and rides his pale horse (Binky) around the Disc giving people their quietus, we’re treated to scenes of Death trying out fly-fishing, crashing a swanky party for the new Patrician of Ankh-Morpork (and joining a conga line), gambling with a handful of Ankh-Morpork’s “legitimate businessmen,” sampling every possible drink at a dive bar, and ultimately working as a short-order cook. Meanwhile, Mort’s turn standing in for Death goes catastrophically badly when he prevents the assassination of a princess with whom he’s smitten and inadvertently warps the fabric of reality by interfering in destiny.

So it goes.

1. Unformed Clay

Mort (1987) is the fourth Discworld novel. It is the first novel to feature Death as a central character. It was also the first instance in which Sir Terry published two Discworld novels in one year. The Colour of Magic was released in 1983, and there was a three year wait for The Light Fantastic. That would be the last time for twenty years that Discworld fans had to wait more than a year for a new novel: from 1986 to the release of Making Money (#36) in 2007, there was at least one new Discworld novel every year. In ten of those years, two new titles were released, and in 2001 there were three.3

Sir Terry said that Mort was the first Discworld novel with which he was “pleased,” (BBC, Bookclub), that it was the first for which the plot was more than scaffolding for jokes. I think this sells Equal Rites a bit short, but I would agree with that characterization of The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic. Perhaps more charitably, one might say that the series of adventures in the first two novels are there to support the jokes in the same way that the questing hero’s adventures in the fantasy they parody are there to give the hero challenges against which to prove himself.4 Still, the point is well taken: Mort has an organizing premise in a way that The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic do not. If, as I suggested in my last post, Equal Rites was the first instance of Sir Terry introducing social and political issues into a Discworld narrative, Mort is where he starts to build out his world. The organizing premise is Death himself; in centring the narrative on him, the novel is obliged to provide a deeper understanding of the role he plays in the world more generally. Though, as I say below, much of Mort is about exploring Death’s humanity, we’re also treated to a more expansive treatment of the laws that govern the Discworld, as well as a better sense of the Discworld’s geography.

To be clear, we’re still a ways off from actually mapping Discworld. The Discworld Mapp, a collaboration between Sir Terry and Stephen Briggs, came out in 1995, the same year as Maskerade (#18).5 As he explains in the introduction to the Mapp, Sir Terry never intended to create one—but by that point, eighteen novels set in the Discworld had effectively created a geography that could be surveyed.

And while we’re far from any sort of definitive sense of geography in Mort, there is a definite sense of the world’s shape—and more importantly, a sense of inhabited places, cities, countries, kingdoms, and so forth, that exist in spatial and political relation to one another. This sensibility is a departure from The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, which—as is appropriate to the kind of fantasy they parody—have a far more nebulous understanding of space and place that corresponds to the conventions of romance. Medieval romance, like many fairy tales, tends to operate on a hic sunt dracones (Here Be Dragons) logic, in which the spaces outside enclaves of safety is unmapped and lawless, spaces in which anything is possible and doesn’t operate according to the rules or laws of reality. So, should you venture out of your village or beyond the castle walls, all bets are off: monsters, gingerbread cottages, wandering enchanters, magical temples, mysterious knights guarding river crossings, homicidal bunnies … all are possible and indeed likely encounters, whether you’re a questing hero or cowardly failed wizard.6

Equal Rites departed from the romance model, providing a more coherent geography, albeit a narrow one that described the journey from the small hamlet of Bad Ass in the Ramtop Mountains down to the city of Ankh-Morpork. Mort is more capacious, as the titular character spends much of the novel flying from place to place on Binky, providing us (almost literally7) with a god’s-eye view of the Disc and its environs. And while distances and proximities are only gestured at, we nevertheless begin to have a grasp of the totality of the Discworld, not merely as a planet-like cosmic thing, but a place of different peoples, societies, kingdoms, nations, and so forth.

2. Murdering a Curry with Death

As I’ve noted before (and will almost certainly note again) Death appears in every Discworld novel but two.8 In The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic he’s a bit of a running gag, showing up whenever Rincewind is in danger (which is frequently), irked by how the hapless failed wizard has consistently managed to evade his end. In The Light Fantastic, Rincewind actually visits Death’s home while having something like an astral vision, and there are some details from that scene that Sir Terry replicates for Mort. In Equal Rites, Death appears in the first pages when the wizard Drum Billet dies. That scene is notable to us because it establishes one of Death’s personality quirks that will persist through the rest of the novels. Just before we see Death conversing with the spirit of Drum Billet, he’s noticed by someone else in the forge: “The white cat purred and arched its back as if it was rubbing up against the legs of an old friend. Which was odd, because there was no one there” (18).

Mort is indeed all about Death’s quirks and about fleshing out Death’s character.9 One of the novel’s central questions considers what it might look like if an immortal and immutable “anthropomorphic personification,” to whom mortal lives are mere blips in oblivion, got curious about those mortals. Sir Terry sums it up nicely in his lecture “Shaking Hands with Death” when he observes that Death “appears to have some sneaking regard and compassion for a race of creatures which to him are as ephemeral as mayflies, but which nevertheless spend their brief lives making rules for the universe and counting the stars” (275).

Death’s attempts to understand and imitate human behaviour is not at all dissimilar to the common SF trope of an alien trying to pass for human or a robot attempting to understand emotions (“What is this thing you call … love?”). This comic fish-out-of-water scenario is most obvious at the Patrician’s party, as Death interrogates the man in front of him in the conga line as to precisely why people engage in such patently absurd behaviour:

“You do it for fun.”

FUN.

“That’s right. Dada, dada, da—kick!” There was an audible pause.

WHO IS THIS FUN?

“No, fun isn’t anybody, fun is what you have.”

WE ARE HAVING FUN?

“I thought I was,” said his lordship uncertainly. The voice by his ear was vaguely worrying him; it appeared to be arriving directly in his brain.

WHAT IS THIS FUN?

“This is!”

TO KICK VIGOROUSLY IS FUN?

“Well, part of the fun. Kick!”

TO HEAR LOUD MUSIC IN HOT ROOMS IS FUN?

“Possibly.”

HOW IS THIS FUN MANIFEST?

“Well, it—look, either you’re having fun or you’re not.” (184-185)

What becomes apparent without ever being explicitly stated is that, though he exists as an immutable principle of existence, Death’s necessary interactions with the mortals whose ends he facilitates affect him in odd and insidious ways. He is not one of them, nor is he of them, but by the time we encounter him he has developed a certain curiosity about them and adopted certain affections and affectations. For one thing, he loves curry, which he describes to Mort—who is unfamiliar with the cuisine—as like biting into A RED-HOT ICE CUBE (31). He takes Mort to Ankh-Morpork for curry and asks his new apprentice what he thinks of the city. While Mort is noncommittal, Death is not. I LIKE IT, he said. IT’S FULL OF LIFE. Before getting to the restaurant, we see again one of Death’s signature traits—his love of cats. Turning down an alley, a suddenly angry Death fishes a sack out of a water butt, in which somebody has drowned a litter of kittens.

THERE ARE TIMES, YOU KNOW, he said, half to himself, WHEN I GET REALLY UPSET … He upended the sack and Mort watched the pathetic scraps of sodden fur slide out, to lie in their spreading puddle on the cobbles. Death reached out with his white fingers and stroked them gently.

After a while something like grey smoke curled up from the kittens and formed three small cat-shaped clouds in the air. They billowed occasionally, unsure of their shape, and blinked at Mort with puzzled grey eyes. When he tried to touch one his hand went through it, and tingled. (32)

It's worth noting here the poignancy of this brief scene. It’s the sort of thing Sir Terry peppers throughout the Discworld novels; for all that they’re reliably hilarious, they don’t lack for such quiet emotional moments. Death’s love of cats10—which is substantive enough that, though his entire existence is predicated precisely on the death of mortal creatures, it still angers him to see kittens callously drowned—is a quality that, for lack of a better word, humanizes Death.

Indeed, the novel is largely an exercise in humanizing Death. It’s right there in the title: when Mort tells Death his name, Death acknowledges the serendipity. WHAT A COINCIDENCE, he says (21), a coincidence not just that Mort has a job-appropriate name but that he also shares his name with his new master, given that mort means “death” in French.

To be clear, any time you anthropomorphize anything you humanize it (it’s right there in the word!). But it’s worth reflecting on this particular humanization of Death, which sets the stage not just for future explorations of the character but for one of Discworld’s pervasive themes.

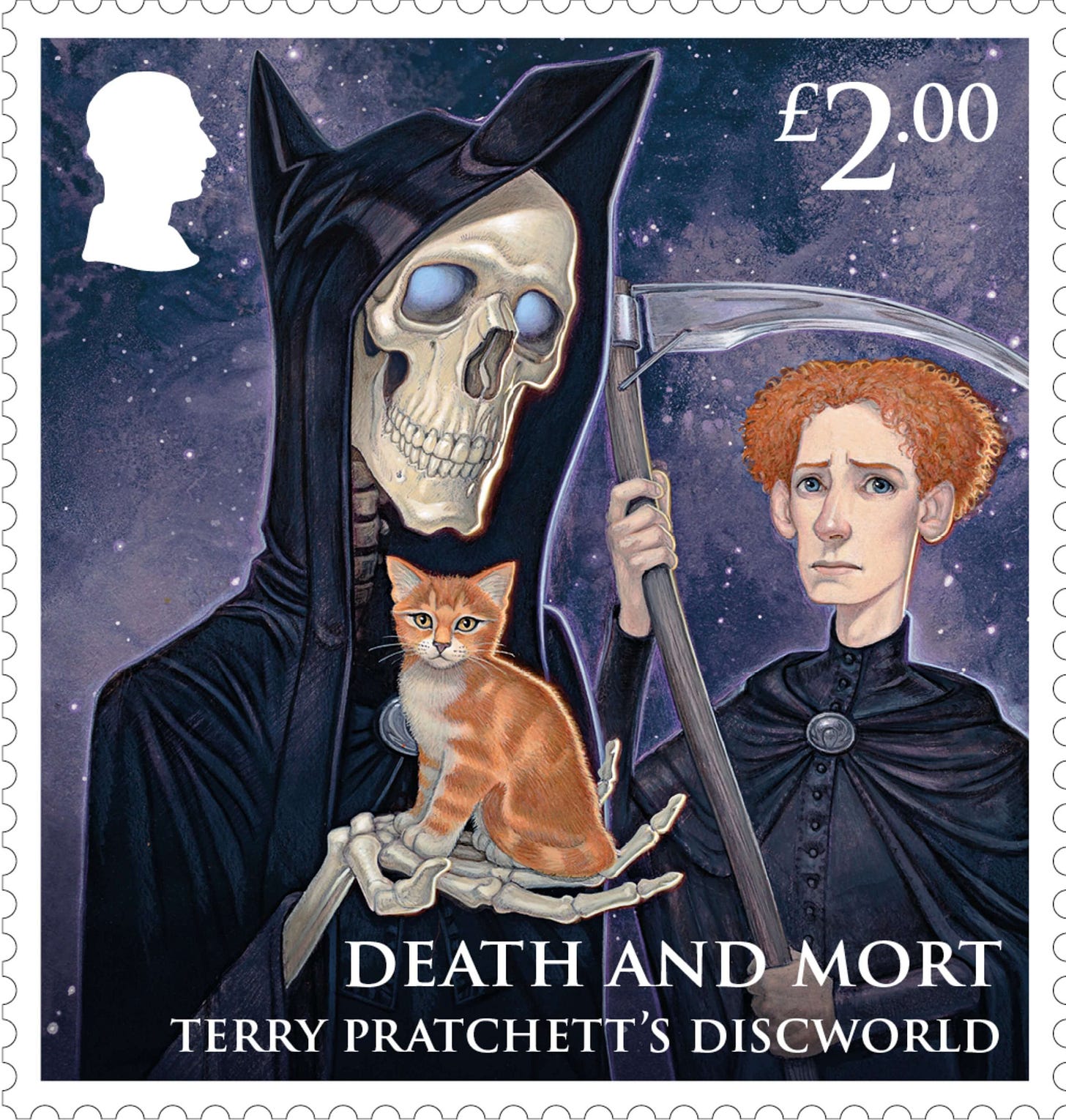

It is notable that Sir Terry’s Death is superficially undifferentiated from the classic figuration of the Grim Reaper. The image of the black-robed skeleton bearing a scythe (or, variously, a sword or sickle) is principally a medieval European creation that emerged in the late thirteenth century but became pervasive in the mid-fourteenth when the Black Plague swept the continent. The figure has persisted, effectively becoming the default depiction to the point where anything different appears a novelty.11 Death himself nods at this fact at times, as in Sourcery (#5—next up!) when Death reflects on the how he’s frequently challenged to “the usual symbolic chess game, which Death always dreaded because he could never remember how the knight was supposed to move” (12). This is an allusion to the infamous chess game between the knight and Death in Ingmar Bergman’ film The Seventh Seal (1957),12 a scene artist Paul Kidby recreated featuring Sir Terry himself.

The fact that Sir Terry opts for the Grim Reaper cliché becomes significant for several reasons. The big one is the basic fearsomeness of the figure: though various understandings of the personification of death emphasize his role as psychopomp,13 that is, as a mere guide for the deceased, his scary aspect and the scythe in his hands often suggests otherwise.14 Much of what Sir Terry engages in is grounded in defamiliarization; what better way to do so than starting with the terrifyingly familiar?

The transformation of death from implacable law of nature to a curious, quirky, and occasionally lonely immortal entity is reflective of Sir Terry’s evolving humanist philosophy more broadly. As these rereadings proceed, I’ll do deeper dives into what I will argue are the consonances and concurrences Discworld has with different strands of liberalism and, especially, pragmatism—and even a smattering of postmodernism—but what’s most important to note here is a point I made above. Namely: Death is what defines mortality and mortal lives, but by the same token Death is himself defined by the mortals for whom he exists. The question is not raised in Mort, but I seem to think it comes up in later novels: what becomes of Death when everything in the universe dies? Does he persist, or does he too come to an end?15 The strong (or possibly explicit, we’ll have to wait and see) suggestion is the latter.

Thus the curiosity and desire to better understand the “ephemeral mayflies” over whose passings he presides suggests that those mayflies aren’t entirely separate and other from Death; rather, they exist in a sort of symbiosis. Sir Terry’s comment, as I quoted above, that we spend our “brief lives making rules for the universe and counting the stars” can also function as something of a meta-comment on the dynamic in Mort, as we also spend our brief lives obsessed with death—going to far as to personify it and give it such human-adjacent personifications as the Grim Reaper.

Mortality is a shared trait, but then so is the kind of mythopoeic impulse that gives us figures like the Grim Reaper. A recurring theme in the Discworld novels is the power of story, both as a means of creating and shaping reality and our most powerful means of understanding reality. Death attempting to understand and experience humanity necessarily humanizes him and sets the stage for the many ways in which Sir Terry’s fiction expands the definition of “human” to be more capacious and inclusive and permeable—less a taxonomic category than a function of the imagination.

3. Sticking a Pin in Destiny

There’s a big part of Mort I’ll now gloss over, in part because I’m already pushing four thousand words for this post, but also because I need to think about it more carefully. Fortunately, it’s a topic to which I’ll have many opportunities to return, and not just with the Death novels.

I’m referring here to destiny and fate. One of the world-building components introduced in Mort is Death’s library of lives and storehouse of hourglasses. The former are the books that tell the stories of everyone who has lived or is still living (the words appear on the page, writing the individuals’ lives before Mort’s eyes); the latter are the hourglasses showing how much time is left in a given person’s life. Both are evocative of traditional figurations of fate: each individual is allotted a certain lifespan, and when Mort impetuously spares Princess Keli of Sto Helit from assassination, he disrupts the flow of destiny.

Fate and destiny, and their close cousin prophecy, are staple tropes of fantasy. One of the significant changes in the genre has been the upending of destiny and other such extrinsically deterministic conventions. Mort starts to play with this in Discworld—I’ll return to this theme in future posts.

But for now, I’ll close things out and return to making notes on Sourcery.

REFERENCES

Pratchett, Terry. “Shaking Hands With Death.” A Slip of the Keyboard.

---. Equal Rites. Corgi, 1987.

---. Mort. Corgi, 1987.

---. Sourcery. Corgi, 1988.

---. Bookclub. BBC Radio Four. James Naughtie, host. 4 July 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00fc3w5.

NOTES

This list is enumerated at the very end of Mort by the Master of Ceremonies at a wedding Death ends up attending. One senses that the list of titles would have gone on interminably had Death not testily interrupted, ALL RIGHT, ALL RIGHT. I CAN SEE MYSELF IN. (311)

Honestly, one of my favourite words because of how silly it sounds in contrast to what it means (an entity that guides people’s souls to the afterlife). It always sounds to me like how you’d describe a particularly insufferable lunatic.

YOU HEAR THAT, GEORGE R.R. MARTIN?

Or herself. But really, in the novels Sir Terry satirizes, mostly himself.

Will I be doing a special extra post on The Discworld Mapp, and the question of fantasy cartography more generally? You bet your arse.

I’ll have more to say in this vein in future posts, both with my Discworld reread and regarding fantasy and cartography as a broader topic. At some point not too far (I hope) in the future, we’ll be doing a video on maps in fantasy; I’m also just generally interested in cartography, both as practice and as literary convention, something I’ve only addressed once so far on The Magical Humanist (“Gulfs of (in) Meaning,” 27 February 2025).

My basic point above, which I won’t belabour in the main text but torture here in a footnote, proceeds from the transformations in fantasy as it at once apes the conventions of medieval romance but also adopts elements of realism in its narrative and world-building logic. Indeed, the very concept of world-building is inflected (infected?) by a realist impulse that desires to grasp and outline the rules and logic of a given world or alternate reality. Part of the point of romance is there’s no necessary rhyme or reason for the weirdness one encounters in the wild. Though there is obviously much in The Lord of the Rings that evokes medieval quest romances, Tolkien established the enduring fantasy convention of establishing not just rhyme and reason for everything in his world, but embedded everything within a granular history, languages with coherent vocabularies and grammars, and of course detailed maps.

But not actually literally, because one of the other elements Mort establishes is that Death is not a god. Death, indeed, ultimately comes for the gods, as they are not eternal. Though the principle of the gods’ existence as predicated on human belief is not yet clearly articulated, it is hinted at.

He is absent from The Wee Free Men (#30) and Snuff (#39). Why? Good question! I shall have to think about it when I get there, I suppose.

Putting some flesh on the bone as it were, amirite? Anyone?

… I’ll see myself out.

Cats play a significant thematic role in Discworld where Death is concerned, as they comprise a link between the supernatural and the mortal world. Cats have always been ascribed quasi-mystical or magical qualities, both revered and vilified for it. As Sir Terry himself said in one of his most oft-quoted lines, “In ancient times cats were worshiped as gods; they have not forgotten this.” Those of us who host cats in our homes (one does not own cats) can attest to the fact that they are uncanny little sociopathic freaks who also managed to evoke the same kind of gibbering mindless affection in humans that we otherwise tend to reserve for infants. Or dogs—but unlike dogs, cats retain their vaguely extraterrestrial qualities, making them at once aloof and imperious and adorable little toebean cuddlebums.

(Never fear, dog lovers: in six more books—Moving Pictures, #10—we’ll meet Gaspode, a dog whose brush with magic gave him intelligence and the ability to speak.)

Sir Terry was a lifelong cat lover and was always alive to this fundamental contradiction in their character. In Lords and Ladies (#14), he memorably notes, “If cats looked like frogs we'd realize what nasty, cruel little bastards they are. Style. That's what people remember.” Reading the final chapter of Rob Wilkins’s biography Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes, one of the details that caught at my heart was that, in Sir Terry’s final days, his cat Pongo (the most recent in a long line) was a constant companion, curled up at his feet.

Even just a year ago, this would have been the point at which I cited the figure of Death in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics (depicted there as a bubbly goth girl) and noted the various ways in which their respective Deaths were consonant.

I’ll not be talking about Gaiman except for asides such as this one, for what I hope are obvious reasons (if the reasons aren’t obvious, you probably need to read a certain New York Magazine article). Given his friendship with Sir Terry and their collaboration on Good Omens, as well as the many points of thematic intersection between Discworld and American Gods, or Sandman, or many of Gaiman’s other writings, not talking substantively about his work will comprise a gap. But I’ll not otherwise be mentioning him for two reasons: (1) I don’t want to give his voice oxygen, and (2) the monstrosity of the credible allegations against him would be a massive distraction from what I’m otherwise trying to do here. So he gets relegated to the occasional footnote at best going forward.

Though knowing Sir Terry’s affection for the characters Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), it’s a reasonable assumption that he was also thinking of Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey, in which Death (William Sadler) makes the mistake of letting Bill and Ted choose the game … and find himself losing when they play Battleship, Clue, and Twister.

Yup, never not funny.

And indeed, the scythe suggested the active harvesting of souls, reaping (one assumes grimly) the living as opposed to merely being present at the moment of death. Given the ubiquity of the Death-as-reaper trope during the Black Plague, the suggestion of motivated malevolence gets baked into that particular cake.

One lovely meditation on this question is in N.K. Jemisin’s short story “On the Banks of the River Lex,” which exhibits an extremely Pratchettian sensibility. In it, Death wanders around a post-apocalyptic New York City following some sort of catastrophe that has wiped out all of humanity. Left populating the city are various deities and entities at loose ends, weakened by the absence of humans to believe in them, so they take turns believing in each other. Death is in so such danger, as he exists for all mortal beings. But, as he reflects, it isn’t the same with unintelligent species—there’s none of the verve and vim of the job that there was with people.

But then Death has an encounter with what might be the next evolutionary leap forward. I won’t spoil what it is.

The story is collected in Jemisin’s book How Long ‘til Black Future Month (2018). “River Lex” can be read in Clarkesworld Magazine.