A quick prefatory note: I’ll be posting a supplemental Sourcery essay shortly. Believe it or not, but these six thousand words weren’t quite enough to say everything I wanted to say. Basically, on rereading this novel I found myself startled at just how elements of it resonate uncannily with the general political shitshow currently playing out in the U.S. (and elsewhere, but mostly the U.S.) I started sketching out the supplemental, but then it started overlapping significantly with something else I’m working on. So I decided against it; then this post started getting really long, and I though “Eh, I can stand to hive off a couple thousand words.” So that’s where we’re at.

In Equal Rites, we learned that the eighth son of an eighth son is destined to be a wizard. But what happens if a wizard abjures his vow of celibacy and proceeds to have eight sons? Nothing good! The eighth son of a wizard is a wizard squared—a source of magic. A sourcerer.1

The renegade wizard Ipslore the Red long ago quit Unseen University, infuriated with its complacency, infighting, and hidebound traditions. Having rejected the university’s staid conventions, he married, having eight sons. At the moment of his death, he cheats the Grim Reaper by transferring his consciousness into his wizard’s staff, which he gives to his infant son Coin. The sourcerer.

Several years later, Coin arrives at Unseen University and, well, proceeds to shake things up. He vaporizes the new Archchancellor, but before he can step into the role, the Archchancellor’s hat—the badge of office and, as it turns out, a sentient magical object—is stolen by a mysterious thief. The thief, we soon discover, is Conina the Barbarian: daughter of Cohen the Barbarian, preternaturally beautiful and even more preternaturally deadly, having inherited all of her father’s warrior talents. Really, though, her true desire is to become a hair stylist. But for the moment, following a compulsion she doesn’t quite understand, she steals into the Archchancellor’s chambers and takes the hat. The hat tells her she needs to take it far away from Ankh-Morpork and the shit that’s about to hit the fan with the sourcerer’s arrival. It tells her to find a wizard to help.

Unfortunately, the wizard Conina finds is Rincewind. Against all his better judgment, he and Conina flee with the hat across the Circle Sea to the nation of Klatch. And that’s when their troubles truly begin.

1. Less-Unformed Clay, or, The Discworld Takes Shape

Rereading Sourcery has been an interesting experience, because I’ve had the vague recollection since first reading it (conservatively, about fifteen years ago) of not liking it overmuch. If you asked me what my least favourite Discworld novels were, I’d probably have mentioned it prominently—though almost certainly without significant detail, just a general sense of “Oh, it’s one of the early Discworld novels before Sir Terry’s getting his feet.” On returning to it now, however, what strikes me is that it’s an early novel in which Sir Terry is very definitively finding his feet.

A host of factors contribute to this: Rincewind sort of develops a spine (which, to the best of my recollection, he never finds again); we spend serious time in a part of the Discworld that’s not identifiably neo-European; the nature of magic and magical power is explored in much greater depth; and, as I get into somewhat below, the central conflict resonates powerfully both in the immediate context of when it was published (1988) and in the present moment. Beyond these factors, however, there is also just the sense, much harder to quantify, of the prose and narrative being more assured, more confident. The jokes land harder as well, not in spite of the story’s greater gravitas, but because of it—I spent a great deal of time laughing out loud as I read, even as I made furious notes about how relevant the key themes are right now.

2. A Few Things, Itemized

As noted above, there’s a lot going on in Sourcery. When I started doing this series I’d had the idea that each entry would contain a list or three: new elements and characters introduced for the first time, where the novel ranks in my personal preferences, the number of times I’d read the novel before coming to it here, and other such things.

Well, it hasn’t really worked out that way. That’s largely due to my temperament, which is more inclined to go down interesting and/or serendipitous thematic rabbit holes than offer recaps.2 But now and then we’ll be doing a novel like Sourcery, which has so many moving parts that it’s probably useful to break things down more systematically.

Rincewind. Again! He’s now featured in four of the five Discworld novels (though his appearance in Mort was little more than a cameo). Sir Terry takes a bit of a break from him for three novels before he returns in Faust Eric (#9), and after that he’s absent until Interesting Times (#17).

Sourcery represents the high-water mark of Rincewind’s character. Or so I seem to think—on rereading this novel I was struck by his thoughtfulness, unusual in his overall corpus. I might well be misremembering, but my sense is that he settles back into the character he had in The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, in which he’s basically an inadvertent chaos agent who can’t get out of his own way as he’s dropped against his will into madcap adventures.

But here in Sourcery he’s obliged to face some weighty questions: about who he is, who he wants to be, and what his place as a wizard (however incompetent) is in the world. At one point when he is concerned about being identified by hostiles as a wizard, Conina points out he can just pretend not to be one—to lose his wizard’s garb and, especially, his hat. To which Rincewind responds with a blank expression, uncomprehending. He is a wizard! “Twenty years behind the staff, and proud of it!” he cries, to which Conina responds, “You’re not actually good at [it], are you?”

Rincewind glared at her. He tried to think of what to say next, and a small receptor area opened in his mind at the same time as an inspiration particle, its path bent and skewed by a trillion random events, screamed down through the atmosphere and burst silently just at the right spot.3

“Talent just defines what you do,” he said. “It doesn’t define what you are. Deep down, I mean. When you know what you are, you can do anything.”

He thought a bit more and added, “That’s what makes sourcerers so powerful. The important thing is to know what you really are.”

There was a pause full of philosophy. (165)

I was struck by this passage for a number of reasons, not least of which is that it doesn’t entirely square with much of what one otherwise encounters, philosophically speaking, in the Discworld novels. Indeed, Conina then says to Rincewind “You really are an idiot. Do you know that?” (166)—so perhaps we shouldn’t put too much stock in his moment of inspiration. On the other hand, perhaps it offers an insight into what the French call déformation professionnelle—even though he has failed at being a wizard in every way that matters, twenty years of immersing himself at Unseen University have left a mark. What Rincewind sees as an innate quality might in fact be his own dogged determination.

In the end, he saves the day—going to the University, determined to face Coin, reigned to the probable futility and fatality of the gesture.

The Luggage. All I have to say about the Luggage is that it is, quite possibly, one of the greatest comic inventions of anything ever written. The sequence running through the middle of the novel in which it ploughs single-mindedly through the desert to return to Rincewind, terrorizing a host of predators and monsters en route is brilliant.

Klatch. We’ve had passing references to Klatch in previous novels, which appears as something of a conflation of Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures, which introduces curry to the denizens of Ankh-Morpork (and which, as we saw in Mort, is Death’s favourite food).

Sir Terry tends to walk a fine line when depicting “foreign” places in Discworld, by which I mean locales that correspond to what parochial British people on Roundworld would classify as foreign. That is to say: hot and populated by nonwhite people speaking strange languages, where the food is suspiciously spicy. Though these depictions tend to satirize the parochialism of the such default-British settings as Ankh-Morpork and environs, or the Ramtops mountains region, they can—especially in the early novels—devolve at times into simplistic stereotypes. To Sir Terry’s credit, these moments are always imbued with gentle humour, but some of his set-pieces haven’t aged well.

Like his principal characters and the Discworld more broadly, however, the less-formed clay of the early novels becomes more complex and thoughtful with each iteration. We revisit Klatch on a number of occasions, most notably in Jingo (#21), which was published in the years following the first Gulf War and takes more specific aim at Western chauvinism and ignorance. Otherwise, we experience Klatch and Klatchian culture mostly through the large Klatchian presence in Ankh-Morpork—especially in terms of the eateries around the city specializing in curry. One of the running jokes is the various ways in which native Klatchian dishes adapt to the more pedestrian culinary tastes of the Morporkians, such as the ubiquitous addition of turnip.

Havelock Vetinari. The Patrician of Ankh-Morpork—whose swank party in honour of his ascension to the role was the one at which Death joined a conga line in Mort—will become one of the most substantive and thematically crucial characters as Discworld evolves. This is the Patrician who’ll be with us for the duration; when we encountered the Patrician of The Colour of Magic, who in his corpulence and ostentatious jewellery is manifestly not the austere Vetinari, I wondered if this were merely an early draft of who Vetinari would become or we’d have a clearer succession.

It turns out to be the latter, and while the riotous party celebrating Vetinari’s ascension in Mort also very out of character, I suppose we can speculate that he felt compelled to hew to convention before establishing his particular style of rule.

Vetinari’s particular style of rule is something I’ll have many occasions to talk about here. Indeed, in truth I’m a bit impatient4 to get to when he’s more fleshed out, as his evolution from a caricature of a Machiavellian leader to a far more nuanced and complex leader who more accurately reflects Machiavelli’s philosophies of governance is one of the major tentpoles of how I understand the political philosophy articulated by Sir Terry.

(Patience, Chris, patience.)

Our initial introduction to Vetinari, however, is ignominious and brief. He is magically summoned by Coin, and without ceremony transformed into a small yellow lizard. He spends the better part of Sourcery in a glass jar in the care of the Librarian.

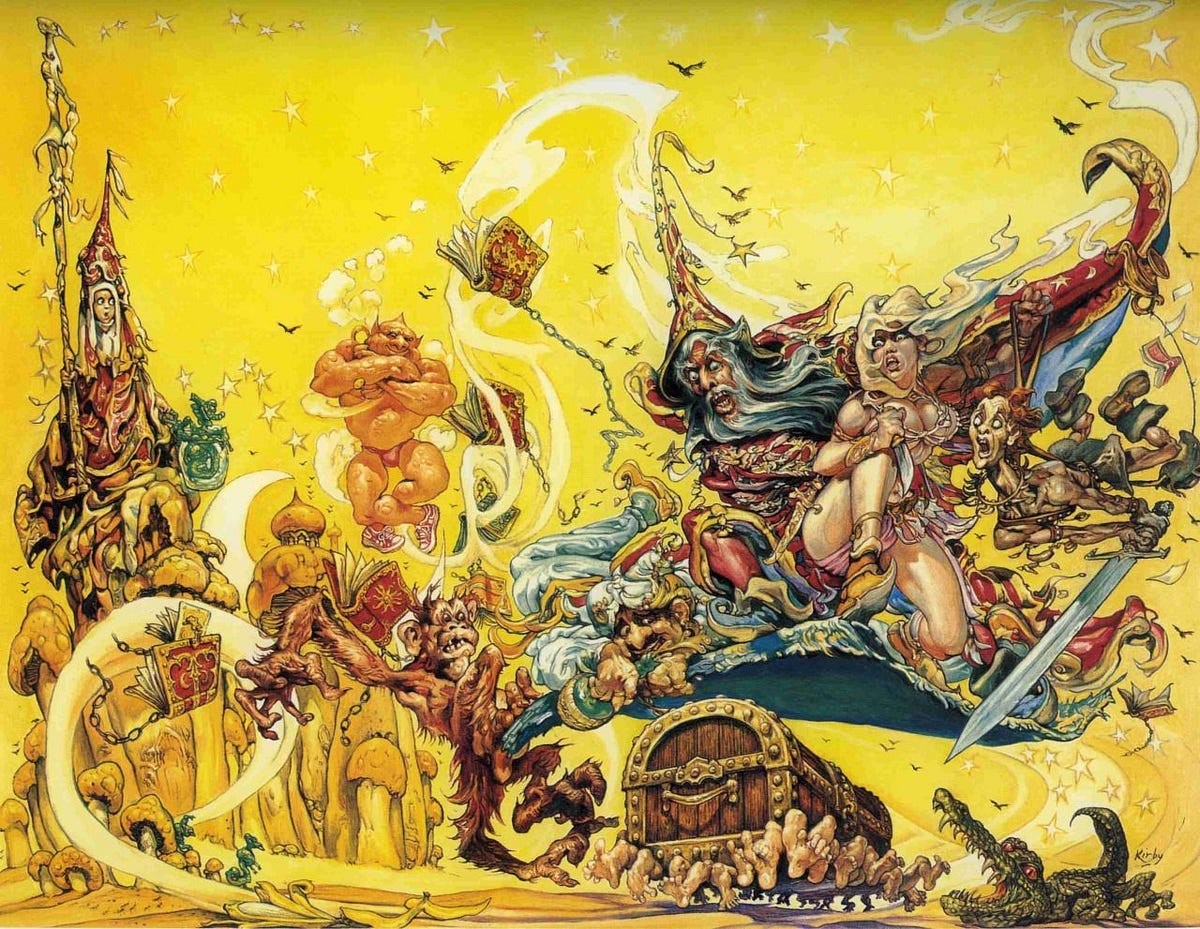

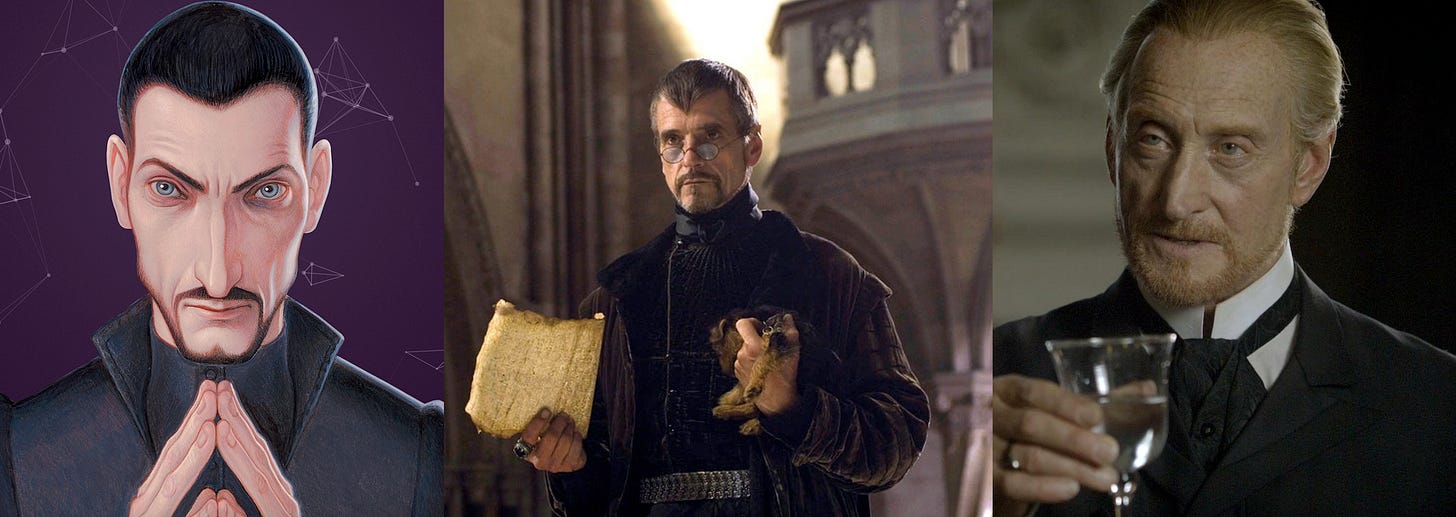

His general aesthetic will endure: he is described as “thin, tall, and apparently as cold-blooded as a dead penguin … He looked the kind of person who, when they blink, you mark it on the calendar” (76). There have been, to the best of my knowledge, two filmic depictions of Vetinari: the first by Jeremy Irons in The Color of Magic (2008), and the second by Charles Dance in Going Postal (2010). Irons is pretty much a bit of dream casting, given that it would be difficult to conjure an actor who better captures the look of Vetinari, especially as rendered by Paul Kidby. Dance, however, captures the Ventinari sensibility in his performance, as this brief clip demonstrates.

The Librarian. Of all the dozens of vivid, weird, hilarious, and poignant recurring characters who come to populate Discworld, the Librarian is one of my favourites. In this I am not alone.5 Transformed from a man into an orangutan by a magical accident, he resists the efforts of some of his fellow wizards to turn him back, finding contentment in his new form, in part because he can now climb through the labyrinthine stacks in the University Library with ease. So long as he has his books and a healthy supply of bananas, he’s happy.

The Librarian, the Library he occupies, and the books crowding the shelves—all of which, being magical books, have lives of their own—are very obviously the creation of an author whose own spiritual and emotional connection to libraries is profound. One of the most affecting parts of Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes, Rob Wilkins’s biography, describes Sir Terry’s first forays into the Beaconsfield Branch Library at the age of eleven. At an earlier age, Wilkins speculates, young Terry would have been indifferent to a big building full of books, but he “was now woken by the power of The Wind in the Willows and actually thirsty for books” (44-45). The Beaconsfield Branch Library was modest but more than satisfactory for young Terry’s newfound need to read: “There was so much to read, and so much to be discovered about how reading worked, and here was a room, smelling of paper and glue and vacuumed carpet, where that discovering could be done” (45). Before long, young Terry wasn’t just visiting the library to drop off books and check out new ones, but just hanging out: “Terry seems to have hung around Beaconsfield Library at the weekends in the same way other people might stand in a guitar shop on a Saturday afternoon—just to be there, in the vicinity of the thing you were passionate about, among your tribe” (46).6

That bone-deep love of the library as a space translates into the arcane Library of Unseen University, with its vaguely sentient books and their reality-warping tendencies.7 Anyone who has known librarians well will immediately recognize Sir Terry’s Librarian: a gentle soul with an encyclopaedic knowledge of his collection who will go absolutely ham8 on anybody harming or disrespecting the books.9

As I’ll get into below, one of the principal ways the novel signals the enormity of the threat posed by the return of sourcery is when Coin determines that the Library is no longer necessary. “[W]ho among you has been into you dark library these past few days?” Coin demands of the wizards. Books are irrelevant in the new magical reality, he asserts: “The magic is inside you now, not imprisoned between covers” (101). Burn it down, he decrees. But when a contingent of wizards led by true believer Benado Sconner take kindling and matches10 to the Library, the otherwise typically gentle Librarian becomes “a screaming nightmare with lips curled back to reveal long yellow fangs” as he attempts “with considerable effort to unscrew Sconner’s head by the ears” (154).

Suffice to say, the Library lives to fight another day. When Rincewind returns to the University late in the novel, however, he finds the Library a burned-out husk. Sitting disconsolately in the ruins, he notes that, for all the charred destruction, there’s not nearly enough ash to account for a library’s-worth of burned books. Investigating a nearby tower, he discovers where they have gone:

The whole tower was lined with books. They were squeezed on every step of the rotting spiral staircase that wound up inside. They were piled up on the floor, although something about the way they were piled suggested the word “huddled” would be more appropriate. They had lodged—all right, they had perched—on every crumbling ledge.

They were observing him, in some covert way that had nothing to do with the normal six senses. Books are pretty good at conveying meaning, not necessarily their own personal meanings of course, and Rincewind grasped the fact that they were trying to tell him something. (216-217)

The Librarian, of course, has rescued the books (though, being magical, many of them managed to flee under their own locomotion), but not without casualties. “Not every book had made it,” we learn. One series “had lost its index to the flames and many a trilogy was mourning for its lost volume.” Many of the books bear “scorch marks on their bindings and some had lost their covers, and trailed their stitching unpleasantly on the floor” (217-218). The Librarian himself is in the midst of performing surgery:11

The ape pushed the candlestick into Rincewind’s hand, picked up a scalpel and a pair of tweezers, and bent low over the trembling book. Rincewind went pale … The ape jerked his thumb again, without looking up. Rincewind fished a needle and thread out of the ranks on the tray and handed them over. There was silence broken only by the scratching sound of thread being pulled through paper until the Librarian straightened up and said:

“Oook.” (218)

I mentioned in my post on Mort that peppered throughout the Discworld series are these surprisingly poignant and emotional moments that take you by surprise—Death freeing the souls of the drowned kittens in Mort, and here the Librarian recapitulating a tense scene from every medical drama ever … with a book.12 I could go on at length about the way Sir Terry literalizes the love of books and the sense of books as living things, but (1) I’ll have plenty of opportunities to go down that rabbit hole in future instalments, and (2) if you get it, you get it.

Humour. One thing I haven’t mentioned much in these posts is just how bloody funny the Discworld novels are. Which, admittedly, is a rather massive omission considering that being riotously funny is the primary feature for which Sir Terry was known.

But here’s the problem with writing about humour: there’s nothing like a quasi-academic, self-serious discussion dissecting why something is funny to ruin a good joke. The point of good comedy is it always already gets there ahead of you. It is the critique, and the way you know it’s effective is because you laugh. Freud was onto something when he suggested that laughter is like dreaming, in that it provides a release for the unconscious: as Shakespeare’s various fools show, jokes can be licensed transgression, either saying the otherwise unsayable or providing contrasts that bring hypocrisies and absurdities into starkly funny relief.13

And there, right there in what I just wrote, exemplifies the problem with intellectualizing comedy, when good comedy is its own form of intellectual discourse.14 Call it composition as explanation, if you like.15 But that, I hope, will suffice to demonstrate why I don’t go on at length about the nature, context, structure, etc. of Sir Terry’s jokes.

That being said, I do want to acknowledge how funny these novels are. The best way is probably to let the humour speak for itself, so let me share one of the sections that made me laugh out loud.

The imminent arrival of a sourcerer and all that portends causes an exodus of the University’s various varieties of vermin. Sensing approaching disaster as the wizards themselves apparently do not, the rats, bedbugs, ants and roaches are all getting the hell out of Dodge. These fugitives aren’t your ordinary creepy-crawlies, however, as “Centuries of magical leakage into the walls of the University had done strange things to them” (20). Alongside the rush of rats and mice are hordes of ants: “Some of them were pulling very small carts, some of them were riding beetles, but all of them were leaving the University as quickly as possible.” Looking up, Rincewind notices “an elderly striped mattress extruded from an upper window,” which then “flopped down into the flagstones below.” The mattress then rises fractionally from the ground and “started to float purposely across the lawn.” Rincewind “heard a high-pitched chittering and caught a glimpse of thousands of determined little legs under the bulging fabric before it hurtled onward. Even the bedbugs were on the move.” It is however the cockroaches who most startle Rincewind, “a shiny black tide flowing out of a grating near the kitchens.”

But it wasn’t the sight of the cockroaches that was so upsetting. It was the fact that they were marching in step, a hundred abreast. Of course, like all the informal inhabitants of the University the roaches were a little unusual, but there was something particularly unpleasant about the sound of billions of very small feet hitting the stones in perfect time.

Rincewind stepped gingerly over the marching column. The Librarian jumped it.

The Luggage, of course, followed them with a noise like someone tapdancing over a bag of crisps. (24)

The fact that all the University’s rodents and bugs are smart enough to GTFO while the wizards are oblivious of the imminent danger until it is too late is an unspoken joke all the funnier for being unspoken.16

Sir Terry often got stroppy when lazy critics assumed his fiction was unserious because it was funny. He was given to quoting a line he attributed to G.K. Chesterton: “The opposite of funny is not serious. The opposite of funny is not funny.” Or as a certain anthropomorphic personification might put it: dying is easy. Comedy is hard.

CATS. I would be remiss if I didn’t also note that Sourcery contains the Discworld lines I possibly quote more than any others. At the beginning when Death comes for Ipslore the Red, he finds the rogue wizard raging against fate. Death is singularly unhelpful, as he is the embodiment of where all roads ultimately lead. When Ipslore says of his infant son Coin, “Children are our hope for the future,” Death replies implacably,

THERE IS NO HOPE FOR THE FUTURE …

“What does it contain, then?”

ME.

“Besides you I mean!”

Death gave him a puzzled look. I’M SORRY?

The storm reached its howling peak overhead. A seagull went past backwards.

“I meant,” said Ipslore, bitterly, “what is there in this world that make living worth while?”

Death thought about it.

CATS, he said eventually. CATS ARE NICE. (11)

3. The Imagination of Apocralypse

Sourcery is the fifth Discworld novel. As I hinted above, it is also arguably the first where it really feels like shit’s getting real. Or perhaps that’s just a side effect of the fact that the world almost comes to an end—Sourcery is certainly the most cataclysmic Discworld novel, even though at least two others also feature a near-Apocralypse.17 Yes, Apocralypse, to be distinguished from your more pedestrian apocalypse: whereas the latter is the subject of specific (if elliptical) prophecies, nobody is certain when, how, or even if the Aprocralypse will happen. As the perspicacious Librarian realizes early on, however, it is often associated with the appearance of a sourcerer. Pulling Casplock’s Compleet Lexicon of Majik with Precepts for the Wise down from the shelf and opening it to “S,” he reads:

Sourcerer, n. (mythical). A proto-wizard, a doorway through which new majik may enterr the world, a wizard not limited by the physical capabilities of hys own bodie, not by Destinie, nor by Deathe. It is written that there once werre sourcerers in the youth of the world but not may there by nowe and blessed be, for sourcery is not for menne and the return of sourcery would mean the Ende of the Worlde … If the Creator hadd meant menne to bee as goddes, he ould have given them wings. SEE ALSO: thee Apocralypse, the legend of thee Ice Giants, and thee Teatime of the Goddes. (68)

The ”Aprocralypse,” one gleans, is an apocryphal apocalypse, a typical bit of Pratchettian worldplay that I don’t have time to unpack.18 The framework given here is a sort of Ragnarök, given the reference to Ice Giants, as well as the “Teatime of the Gods” (slightly earlier in the day than the Twilight of the Gods).19 What is significant about Ragnarök is that, as mythic apocalypses go, its ending is quite dire. No living on in paradise for the virtuous after the final battle: the Norse vision of the End Times has everyone and everything meeting their definitive demise.

It's worth noting that “apocalypse” in the colloquial sense is quite different from the literal sense. We use it to mean the end of the world; what the word actually means is “revelation,” though to be fair, the revelation with which it is most associated is the end of the world as revealed to St. John the Divine of Patmos. But even here we should distinguish between the religious and mythic understanding of the End Times and the secular apocalypse. The former usually entails not just end times but the end of time, the destruction of the temporal universe. Secular apocalypse generally means the end of humanity or possibly all life on Earth—with, presumably, our planet continuing to spin on through the void.

Sourcery offers a conflation of both understandings, insofar as the Apocralypse echoes the Biblical Armageddon—with the Four Horsemen riding even as the Ice Giants ride their glaciers across the Disc—while the precipitating action resembles the kind of cataclysmic nuclear conflagration that haunted the imagination of the Cold War. Sourcery, as distinct from wizardy, is framed as elemental magic, which has almost infinite capabilities. Two millennia earlier there had been sourcerers, but the wielding of that power by mere men proved so catastrophic that its memory long proved a guard against people seeking it out again. “The world had sourcery once,” the wizard Spelter reflects, “and gave it up for wizardry. Wizardry is magic for men, not gods” (118). Sourcery, he thinks, is “not for us. There was something wrong with it, and we have forgotten what it was.”

Wizards are, as a group, also ill-suited to wield power for the purposes of governance as Coin wishes them to do: “Hand any two wizards a rope and they would instinctively pull in opposite directions. Something about their genetics or their training left them with an attitude towards mutual co-operation that made an old bull elephant with a terminal toothache look like a worker ant” (37-38).20 Though not an explicit suggestion, magic itself might be a factor in this natural obstreperousness: “Magic uses people,” Rincewind later tries to explain to his companions. “It affects you as much as you affect it … You can’t mess around with magical things without it affecting you” (186).

Hence, the return of sourcery to the Disc is a profound threat because such power was never meant to be wielded by mortals with a tendency toward pettiness and ego. Before long, the wizards of the University have fallen into factions, each building their own wizard tower and attacking each other over great distances with magical bombardments whose description evokes the sort of nuclear blasts that plagued the Cold War cultural imagination (albeit less firestormy and with comic elements):

He'd almost reached the fire when the blast from the last spell reached them. It had been aimed at the tower in Al Khali, which was twenty miles away, and by now the wavefront was extremely diffuse. It was hardly affecting the nature of things as it surged over the dunes with a faint sucking noise; the fire burned red and green for a second, one of Nijel’s sandals turned into a small and irritated badger, and a pigeon flew out of the Seriph’s turban.

Then it was past and boiling out over the sea. (198)

Sourcery has a lot of the madcap adventuring we saw in The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic—and indeed, as we see in any story centred on Rincewind, as his tendency is, to paraphrase Tolkien, to flee from peril into abject and mind-numbing terror. But Sourcery exhibits the quality of many Discworld novels, in which the kinetic hilarity of its comedy serves to distract from the fact that the substance of the story is serious as a heart attack.

But more on that in my supplemental post, coming soon.

REFERENCES

Pratchett, Terry. Sourcery. Corgi, 1988.

Wilkins, Rob. Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes. Doubleday, 2022.

NOTES

At some point I’m going to have to write an extra post on Sir Terry’s use of puns. There’s a wealth of them just in his novels’ titles alone. My favourite might actually be in Sourcery, when the term used to describe a state of being under magical rule is … “martial lore” (164).

<chef’s kiss>

I think even my father rolled his eyes at that one.

I’m very aware that I could probably build a larger readership if I wrote shorter, recap- and list-based posts that had staple components like “funniest line” and “best footnote,” but that wouldn’t be me. That’s not to throw shade at recaps and listicles, which are two of my favourite internet genres; I’m just a nerd and a humanities professor (the Venn diagram of those two categories would show the latter circle entirely contained by the former), which lends itself to digressive circumlocution and the kind of verbosity that employs terms like “digressive circumlocution.” All of which is to say: if you read these posts in their entirety and, indeed, are reading this footnote? You’re my people.

The phenomenon of inspiration was explicated some thirty pages earlier:

It is a well-known and established fact throughout the many-dimensional worlds of the multiverse that most really great discoveries are owed to one brief moment of inspiration. There’s a lot of spadework first, of course, but what clinches the whole thing is the sight of, say, a falling apple or a boiling kettle or the water slopping over the edge of a bath. Something goes click inside the observer’s head and then everything falls into place. The shape of DNA, it is popularly said, owes its discovery to the chance sight of a spiral staircase when the scientist’s mind was just at the right receptive temperature. Had he used the lift, the whole science of genetics might have been a good deal different.

This is thought of as something wonderful. It isn’t. It is tragic. Little particles of inspiration sleet through the universe all the time travelling through the densest matter in the same way that a neutrino passes through a candyfloss haystack, and most of them miss. (130)

I’m impatient to get to a LOT of things—the Watch, the translation of Roundworld technology through Discworld magic, the Death of Rats, the existence and life of gods. Thank Offler Wyrd Sisters is next up.

Book people get this. There’s a therapeutic quality to just being around books, whether in a library’s stacks or a bookstore. When I go out to “run errands,” my wife knows that one stop will inevitably be the bookstore—sometimes to buy, but often just to wander among the shelves. “Say hi to the books for me,” she aways says as a go out the door.

We don’t get any discussions of L-Space in Sourcery, but we see hints. L-Space, as we’ll learn in future novels, is the principle that a critical mass of books warps space and time around them, opening up portals to past and future, but most often to other libraries. All libraries, L-Space dictates, are thus connected.

Please be warned: when we finally get to discussing L-Space in greater depth, I will be going off on a massive digression about Jorge Luis Borges and “The Library of Babel,” as well as various other fantasy and fantasy-adjacent library depictions. I would not be at all surprised if it requires its own post. (Oh, and those of you reading this footnote who are now impatient for that future post? You’re my people.)

Perhaps my favourite Discworld expressions that becomes commonplace in the later novels is a euphemized version of “apeshit.” As in: “When Commander Vimes finds out what Nobby’s done, he’s going to go absolutely Librarian-poo!”

Anyone who has actually gotten to know librarians as a group can attest to three basic facts: (1) they are profoundly intelligent and passionate people who will reliably nerd out if you bring them a challenging research question; (2) they can and will drink you under the table—don’t even try to match them drink for drink; (3) if you do anything to harm their books, THEY WILL CUT YOU. You have been warned.

They have to do it the old-fashioned way rather than employing their newfound magical powers because magic cannot be deployed against magical books. A neat little bit of jiu-jitsu on Sir Terry’s part, though it does have a bit of the flavour of the old Doctor Who cheat, “fixed point in time and space, nothing I can do.”

Runner-up for best pun: the surgery being performed on the book? An appendectomy.

Not to get ahead of myself, but there’s a scene in Witches Abroad (#12) featuring a wolf in grandma’s clothing and a woodsman that reliably makes me cry.

All of which is why so much of the argument and discourse around comedy these days obsesses over “edgy” humour and various people’s complaints about getting “cancelled” over telling offensive jokes. “I’m a comedian, it’s my job to be offensive,” is a not-uncommon line. Which strikes me as wrong-headed? If you’re a comedian, your job is to make people laugh. If that laughter is uncomfortable, well done—you’ve threaded a needle. But so much of what gets classified as “edgy” these days (along with the related bastardization “edgelord”) isn’t so much about balancing on the edge of something as pole-vaulting over it.

Some of it is, anyway. The best comedy has a profoundly intelligent basis, even if it’s silly. See above footnotes regarding Sir Terry’s puns.

With apologies to Gertrude Stein.

Unsurprisingly, seeing the exodus of vermin, Rincewind—not infrequently described in rodent-like terms—also chooses that moment to scarper.

Thief of Time (#26), as well as The Light Fantastic, which features a scene of Death sitting with the other Four Horsemen as they wait and see whether their services will be needed.

But in the immortal words of Ben Wyatt, it’s going to bug me if I don’t. Apocryphal is the adjectival version of apocrypha, which refers to texts of doubtful authority or authenticity. When capitalized, “Apocrypha” refers to non-canonical books of Scripture, that is, books and chapters excluded from the Bible by a series of papal decrees in the early centuries of the Church. More colloquially, we use it to mean something false or untrue that has nevertheless gained a certain traction, like the tale of George Washington chopping down a cherry tree or the lady who attempted to dry her dog in the microwave. More interestingly, according to the OED, one now-obsolete usage has it meaning “Things which are hidden or obscure; secrets, mysteries.” Apocalypse, by contrast, means revelation or unveiling: in the final book of the bible, apocalypse refers not to the end of the world per se, but the end of the world as revealed to St. John the Divine (hence, “The Revelation of St. John,” or simply, “Revelations”).

In a fun little bit of serendipity, the Biblical Apocrypha contains a bunch of depictions/predictions of the apocalypse, attributed to such apostolic luminaries as Paul, Peter, Stephen, James, as well as a second, apparently supplemental apocalypse from St. John (though this is considered a false attribution). So, if you like, there’s a veritable library of apocryphal apocalypses, though none though to combine the words into Apocralypse. A failing on the part of Biblical scholars, in my view.

Also reminiscent of Douglas Adams’ second Dirk Gently novel, The Long Dark Teatime of the Soul. Which, as it happens, was also released in 1988.

Wizards are, in this respect, very much like the academics of whom they are an obvious parody. Reading descriptions like the one just quoted triggers memories of every contentious department meeting I’ve ever sat though.

Thank you for this. I had given up some of my love for TP’s work, though not for him; his last books were… not him, and his daughter’s efforts to finish them were misguided. You’ve made me remember a better time. I’ve always liked reading, but Pratchett made me fall in love with it. Back to the beginning I go! Keep on with these if you can, really enjoying your thoughts.

“YOU'RE ONLY PUTTING OFF THE INEVITABLE, he said.

That's what being alive is all about.”

One of the best quotes from Pratchett, to my mind.