Went to see 28 Years Later, and I have some thoughts! Early thoughts, unformed and embryonic thoughts, but thoughts nonetheless. Among my various teaching and research enthusiasms, I do a lot with post-apocalyptic narrative and its most ubiquitous subgenre, zombie apocalypse1—for which 28 Days Later (2002) was almost as much of a game-changer as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). So, a third 28 Days film, coming eighteen years after the second, is pretty much catnip to me.

And I’ll say up front: I loved it, in spite of the fact that it was utterly unlike what I expected. Although I shouldn’t say “in spite of”—it’s a rare experience to see a movie, especially these days, that surprises you. I honestly had no idea what was going to happen next, and that in itself was worth the price of admission.

Once again, my thoughts have proven too expansive for a single post, so I’ll be publishing a follow-up in a day or three. Here I’ll delve into the movie proper; in the follow-up I’ll really nerd out over how 28 Years Later starts to develop common themes with the New Weird. Given my teaching this past term, that makes it a “Curriculars” post (putting aside the fact that classes ended two and a half months ago).

But first, a warning.

All good? Then let’s dig in.

1. The Jimmy of it All

I suppose I’ll start with the one big problem at the heart of the film: it isn’t scary. Like, at all. I mean, there are some tense moments and one or two jump scares and there’s definitely a lot of creepiness, but it has nothing like the abject terror I experienced watching 28 Days Later. Nor 28 Weeks Later, which while being an inferior film contained two of the scariest sequences I’ve ever seen—the opening scene when infected overwhelm a house of survivors, and then the scene in the London Underground, much of which we experience through a night-vision rifle scope, when an infected Robert Carlyle stalks his children.

All of which makes the lack of scares in 28 Years Later perplexing. It’s not as if the director and writer don’t have game; Danny Boyle and Alex Garland, who collaborated on 28 Days Later, both have more cinematic talent in their little fingers than legions of Hollywood hacks have collectively in their entire bodies. If they had put their heads together with the intention of scaring the shit out of audiences, I’d be shopping for new jeans today.

Which suggests … not bringing the scary was a deliberate choice? Which if true is an odd choice, and daring in its own way, as it risks annoying people whose entire reason for watching the movie is to be as scared as they were by the first two.2 Though she generally liked the film, my wife was one of those annoyed people—she genuinely loves being terrified by movies, and so her instinctive response on leaving the theatre was negative. I, by contrast, am not so fond of being scared, and not being constantly on edge or watching much of the movie through slitted eyes meant I was able to appreciate the story and its complexities much better on first viewing than is standard for me with horror films.3

One thing that’s important to note is that this is the first film of a planned trilogy, The second, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, written by Alex Garland and directed by Nia DaCosta, is already done and in post-production, and set to be released in January 2026. The third instalment, for which Danny Boyle plans to return, will be waiting on how the first two do. This is information I kind of wish I’d had going into the movie—as much as I enjoyed it, there are elements that feel underdeveloped, and in hindsight you can see how much table-setting is being done. The ending is especially jarring, and not only because it feels like a cliffhanger or the first few sentences of a next chapter; it is also one of the most bizarre tonal shifts I’ve ever experienced in an otherwise aesthetically and thematically seamless film. It makes the prologue comprehensible: at the film’s start we flash back to the initial outbreak twenty-eight years ago. Young Jimmy sits with other scared children watching Teletubbies while something bad is going down outside. We of course know what the something bad is, and soon enough infected adults break into the room and attack the children. Jimmy manages to escape and runs to the church where his father, the pastor, kneels before the altar in something like religious ecstasy. Judgment Day is at hand, he excitedly informs his son but retains enough paternal instinct to hand him his gold crucifix and tell him to run. Jimmy hides in a confessional just as hordes of infected smash through the stained-glass windows and swarm over Jimmy’s father.4

The story of the film’s present day seems mostly unconnected to the prologue. Spike (Alfie Williams) is twelve years old; his father Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) thinks that makes him old enough to go to the mainland for the first time and kill his first infected. Others—most notably Spike’s ailing mother Isla (Jodie Comer)—disagree (Isla quite vehemently), but Jamie is adamant, and so off they go. My first thought was that Jamie was Jimmy, just having changed up which “James” variant he goes by,5 but once on the mainland we see “Jimmy” written in manners and places that suggest a more ominous meaning for the name. Most notably, Spike and Jamie come across an infected hung by his ankles with a bag over his head and JIMMY carved in his skin down his spine. The suggestion is that the unfortunate man was uninfected when hung like that and probably tortured and left for the infected to find.

We finally meet Jimmy in the film’s final moments,6 identifiable from the gold crucifix his father had given him, which now hangs upside-down around his neck. He appears to save Spike from an onrushing horde of infected with his team of tracksuit-wearing parkour enthusiasts.

Yes, you read that correctly. Brightly coloured tracksuits that evoke the Teletubbies on the TV in the prologue, as well as the standard gear of the late unlamented Jimmy Savile.7 And a gleeful, acrobatic method of dispensing with the infected that is in shocking contrast to the sombre and grave tone of the rest of the film.

I have to assume this final scene sets the tone for what’s to come in the second film. Honestly not sure what I think about that. I guess check back here in January …

But to return to the matter at hand: 28 Years Later, for all intents and purposes, is two films, as the first half and the second half tell stories that are thematically different (though obviously related). The first sets up the world and in its depiction of pastoral island life places 28 Years Later at least partly in the realm of folk horror—the vibe is far more Wicker Man than Dawn of the Dead. The main action revolves around Spike’s fraught relationship with his father Jamie, and his first foray onto the mainland to kill an infected—a rite of passage, it would appear, for everyone on Holy Island.8 The second half is a mother/son drama: disillusioned with his father’s lies and infidelity, Spike sneaks off the island with his mother to seek out a doctor he’s heard about, whom he hopes will be able to cure Isla.

As I said: two stories, both alike in dignity, but which are quite distinct from each other. So, to address them in order …

2. Little Britain

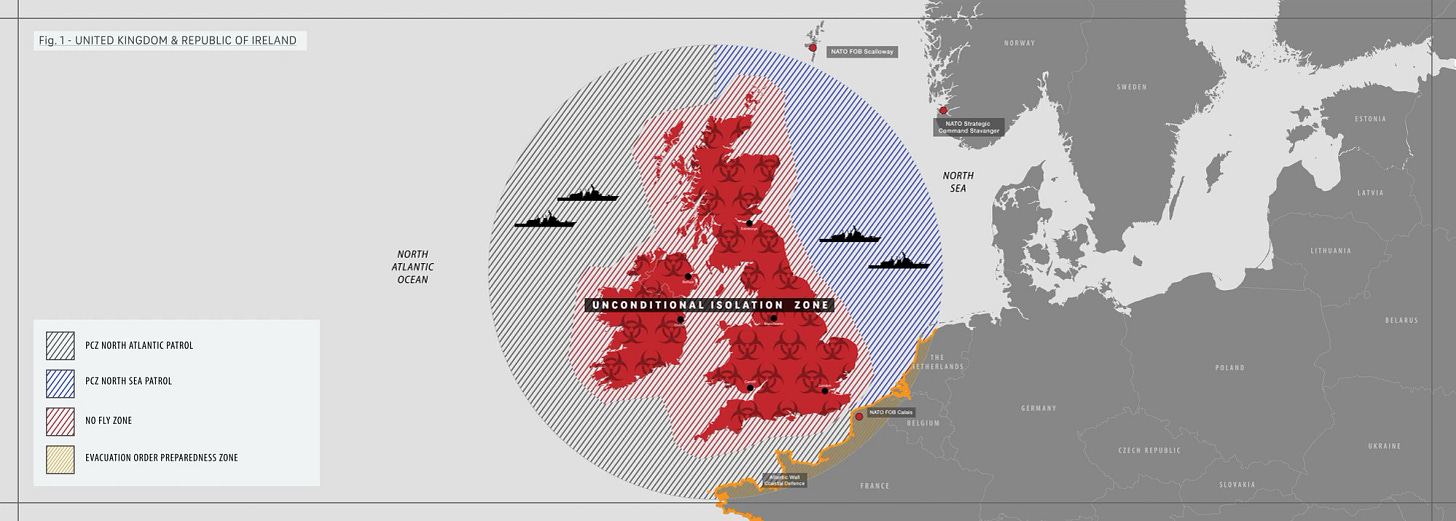

After the opening flashback to the start of the outbreak and little Jimmy’s escape, we are informed by text on the screen that the Rage Virus had been “pushed back” from Continental Europe9 and contained in the British Isles, which are now under absolute quarantine enforced by NATO naval blockade.

Even if that’s all you know about the film, you know enough to grasp that there’s a post-Brexit allegory here—Britain isolated and alone and, cut off from the world, descending either into barbarism or vaguely medieval village life.10 This particular theme becomes inescapable right out of the gate, as the first image we see as we shift from the screen text exposition to the film’s present day is a worn St. George’s Cross flag flapping in the wind. Holy Island11 is home to a small population of survivors who have built a society in the safety of a place whose only connection to the mainland is a narrow causeway that disappears at high tide. Here life has reverted to premodern, pastoral basics: farming, foraging, sheepherding, all of which takes place in a bucolic landscape reconquered by nature in which the vestiges of civilization appear as crumbling relics. As the English flag indicates, life on Holy Island is resolutely British to the point of fetishism. Though the clothing and various objects littering the background (such as Spike’s Power Ranger action figure) reflect a world clock that stopped in 2002, the décor in public spaces is more evocative of the early years of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign. Thy are decorated with wall hangings of the “keep calm and carry on” variety, all of which look handmade and display pithy expressions of fortitude and duty. Frequently seen as well is a portrait of a young Elizabeth wearing her crown.

It's here in the establishing sequences on Holy Island that the Brexit vibe is strongest: an isolated and self-sufficient island hewing to a traditional way of life is very nearly an outright satire on the sentiments expressed by the most ardent Brexiteers.12

Holy Island’s return to a premodern existence within the crumbling homes and artifacts of the late twentieth century, along with the aforementioned signifiers of mid-century Britain, comprise a striking palimpsest layering 2002, the 1950s, and the Middle Ages. The island is essentially a fortified medieval town: an old, ruined castle13 lowers over the village, and the one point of contact with the mainland—the causeway—is guarded by a wooden palisade armed with ballista. The principal weapon is the longbow, which we see the island’s children training with.

The film’s first half features extradiegetic clips from a variety of other films and newsreels, edited in at key moments. There are, for example, brief flashes from 28 Weeks Later: the moment of crisis when the Rage Virus has erupted within the protected compound, and a horde of people run in a panic, which we see through a sniper’s scope. But there are also old black and white scenes of both British soldiers and uniformed schoolboys marching. If you’ve seen any of the trailers for 28 Years Later, you’ll recall the oddly unnerving recitation of Rudyard Kiplings’s poem “Boots.”14 A sample:

Seven—six—eleven—five—nine-an'-twenty mile to-day —

Four—eleven—seventeen—thirty-two the day before —

(Boots—boots—boots—boots—movin' up an' down again!)

There's no discharge in the war!

Don't—don't—don't—don't—look at what's in front of you.

(Boots—boots—boots—boots—movin' up an' down again);

Men—men—men—men—men go mad with watchin' em,

An' there's no discharge in the war!

The recitation recurs in the film and is used to similar effect, paired with images of soldiers and warships. The poem itself was first published by Kipling in 1903, written about the Boer War. More specifically, it’s about the experience of infantrymen endlessly marching with mindless purpose.

The balance of extradiegetic clips, however, are from films set in the Middle Ages featuring mailed and helmeted bowmen loosing arrows. The film most prominently featured is Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1944), which was released during the Second World War and was partly funded by the British government—Winston Churchill told Olivier to do the film as a morale booster for his war-weary countrymen.

All of which goes a long way to emphasizing the film’s thematic preoccupation with England and certain ideas of Englishness. One might go so far as to call it heavy-handed, but it leaves enough ambiguity to pose the question: is this fetishization of Englishness nostalgic or critical? In other words, does this Brexit fable endorse or reject the premises informing Brexit? My own sense is that the ambiguity is deliberate, and while one can certainly read the film as a trenchant critique or even satire of the cultural chauvinism that empowered Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson in the run up to the vote, it’s a rare zombie apocalypse that isn’t embedded in a matrix of nostalgia. However terrible the future depicted, it’s also an expression of wish fulfilment.15 I don’t think I’ve ever seen this fact of the genre better expressed than by comedian John Hodgman:

The zombie epidemic story … is consistently popular for a simple reason: when chaos consumes civilization, you can start over. You get to be young again. All your debts, real and emotional, are canceled. Whatever your dumb job used to be, it has now been replaced with the sole, exciting occupation of survival via crossbow or samurai sword. You get to dress up and wear armor or an eyepatch. And since your neighbours have now been transformed into the idiot monsters you always believed them to be, the zombie epidemic offers you moral permission to shoot them in the head, finally. (5)

This last element is one of the more troubling aspects of the zombie genre, but also, of course, a large part of the basis for the genre’s appeal. This indeed is the point of 28 Years Later’s first act: in his father’s opinion, Spike is old enough to become a man, which in this world entails killing an infected. Spike is, to put it mildly, ambivalent about this prospect and exhibits moral qualms. Jamie assures him that the infected are no longer human, and so he shouldn’t think twice about killing them. But he also follows that up by encouraging him to kill more, as the more you kill, the easier it gets.

Jamie’s blithe unconcern with killing and his casual relationship to the truth—among other things, he greatly embellishes Spike’s achievements when they’re safely back on Holy Island—troubles Spike even as he obviously craves his father’s approval. The rite of passage he endures, though technically a success, sits poorly with Spike and his need for paternal approval is shortly outweighed with his disgust over Jamie’s mendacity and infidelity, as well as concern for his ill mother. Having gleaned that one of his father’s lies regarded the strange hermit Kelson—whose fire they see in the distance—whom Jamie neglects to mention is a doctor, Spike decides to take his mother onto the mainland in search of this doctor and a cure.

3. Memento mori

If the film’s first part is all about a traditionalist father/son dynamic about the son living up to paternal expectations by “toughening up” and proving himself worthy through the exercise of violence, all embedded within a framework of premodern Englishness, the second part is more contemplative, as much a meditation on death and memory as quest story. And where Jamie is ultimately shown to be feckless and childlike, Isla—despite her grave illness and episodes of dementia-like confusion—exudes a gravitas redraws the family dynamic of the first part. Her very name literally means “island,” which symbolically associates her with the safety and comfort of home.

But of course she is not at home, not in her own mind nor on the protective island as Spike takes her across the causeway. In her confusion, she doesn’t know where she is going; in spite of a moment of panic when she comes back to herself, she allows Spike to convince her to find the doctor. As they cross beautiful, flower-smitten fields, her mind wanders, remembering her pre-apocalypse childhood when her father took her on trips through the countryside. She confuses Spike with her father but is in her right mind when she ruthlessly kills an infected to protect her sleeping child.

As they make their way to Kelson, the come across a Swedish soldier, the sole survivor of a squad whose boat foundered. Erik (Edvin Ryding) offers a bit of comic relief as he contemplates his new life—once ashore, he tells them, he can never go back—and provides a contrast between the premodern life of British survivors and the high-tech world that has left them behind. The three of them encounter a pregnant infected woman in the midst of labour. Isla helps her through the process as she births an infant girl, miraculously uninfected. When she reverts to her homicidal default, Erik kills her. He is about to kill the infant too, when an Alpha (presumably the father) literally rips his head off. Fleeing the enraged giant (who chases them with poor Erik’s head in his hand), they are saved by Dr. Kelson (Ralph Fiennes) who knocks him out with a morphine-laced blowdart.

OK: so there’s a bunch of stuff I’ve just described that represents this film’s evolution and development of the 28 Days lore. Most notably: infected can get pregnant? Their children are uninfected? Also: there are new varietals of infected. In the first part we meet the slow-lows, a corpulent strain of infected who crawl along the ground eating worms and grubs. And there are now “Alphas,” huge, tall males with what appears to be somewhat greater intelligence than others. The Alphas ride herd over groups of normal infected, who under the Alpha’s dominance seem to form vaguely primate societies like those of chimpanzees.

That’s all new and interesting, but I’m not going to talk about it here. I’ll instead dig deep into the implications of these developments in my follow-up post.

I’m basically happy to watch Ralph Fiennes in anything, and he does not disappoint here. His Dr. Kelson is eccentric, but gentle and thoughtful. He has spent all these years gathering the dead and turning their bones into a giant open-air temple: tall towers of bones in concentric circles surrounding a central shrine built of the skulls of the dead. He has devoted himself to this project, he tells Spike and Isla, as a memento mori, a reminder of our mortality. It becomes clear that he has killed none of the dead comprising his structures, merely gathered their corpses and rendered the flesh from the bones. He does not even kill the Alpha (whom he has named Sampson).

It is thus sadly appropriate that he should tell Spike and Isla that she has very advanced cancer that has either migrated from her body to her brain or vice versa. There is, he says gently, no cure. At first Spike is incredulous; Isla however receives the news with the quiet acceptance of having knowledge confirmed.

The second part of 28 Years Later departs rather significantly from the conventions of the first two films, and nowhere more significantly than in the bone temple scenes. I was not particularly scared at any point during the movie, but this part was heartbreaking—I was tearing up during Kelson’s diagnosis and his speech about “There are many kinds of death,” and then Spike’s slow acceptance of his mother’s fate. He does not object when Kelson offers Isla a peaceful death, nor does he rage at the doctor when he hands Spike his mother’s skull to place atop the central shrine.

Through all of this, the noninfected infant is a weighty presence. Her significance hangs over the action as an unanswered question (which I’ll address in my follow-up), but also as a symbolic counterpoint to Kelson’s memento mori and Isla’s death. That Spike names her after his mother and returns her to Holy Island emphasizes what, for lack of a better expression, we might call the circle of life (cue Elton John).

Notably, Spike himself does not return, but travels inland, ultimately running into Jimmy and his tracksuited cultists. It is perhaps ironic that Spike comes of age not after learning to kill with his father but learning to accept death with his mother. At the end of the movie, he has become his own man, by way of love and learning to say goodbye.

Which is, I think it’s safe to say, a far more hopeful way to end than we had in the preceding films.

REFERENCES

Hodgman, John. Vacationland: True Stories from Painful Beaches. Diversified, 2017.

NOTES

And here I offer the mandatory disclaimer: yes, the “infected” of the 28 [measure of time] films are not, strictly speaking, zombies. That is to say, they are not reanimated dead, but live people whose minds have been obliterated by the Rage Virus. So I cede that point. But structurally, these are totally zombie films.

The argument over fast vs. slow zombies is one I’m not about to litigate here.

There was indeed a small exodus of about a dozen people from our theatre at the halfway point. They were all young, and they filed out quietly, so I can’t say for certain why they bailed on the movie. But if I had to guess …

It’s a bit of a contradiction, but I love good horror films while also not dealing well with being scared in the moment, especially when the movie is extremely tense and full of jump scares. My preferred method of watching genuinely terrifying films is on my iPad while I play a turn-based computer game like Civilization. Once I’ve inured myself to the scary bits I can rewatch the film with greater scrutiny. My wife, conversely, was allowed to watch Alien when she was ten and has never looked back. Now one dialect of our love language is when I agree to go see a scary movie with her in the theatre.

This scene as featured in at least one of the trailers had me convinced that the church would prove to be the same downtown London church in which Jim (Cillian Murphy) first encounters an infected.

There are a number of Jameses at work here: Jimmy and Jamie, and Cillian Murphy’s Jim in the first film. I actually went to the 28 Weeks Later iMDb page to check and see if there were any there, but there are no Jameses in the second film. But then, that wasn’t an Alex Garland joint. One wonders if there’s a greated symbolic significance to the name, or whether it’s just one of Garland’s go-tos.

Played by Jack O’Connell, most recently seen as the Irish vampire Remmick in Sinners. I was familiar with him previously from his portrayal of the mercurial—or possibly simply insane—Irish commando Paddy Mayne in the series SAS: Rogue Heroes. Anybody who likes WWII drama based in actual history should check it out; it’s based on Ben McIntyre’s excellent book of the same name, and hews pretty closely to the actual historical figures and events (with some fun anachronistic flourishes, like an AC/DC-heavy soundtrack). And if you haven’t yet seen Sinners … well, what are you doing? You need to watch that film, not least so you can read my review of it without concern for spoilers.

As someone born and raised in Canada, I’d had no idea of who Jimmy Savile was. His death in 2011 and the subsequent horrific revelations about his lifelong sexual predation made only a small impression at the time; since starting to write this essay, I’ve gone down an appalling rabbit hole in which I’ve learned way more about him than I ever wanted to know. Suffice to say, there has been a lot of commentary and speculation about the very obvious allusion to Savile in the appearance of Jimmy and his cultists—one point often made is that in 2002, when the Rage outbreak first occurred, allegations of Savile’s crimes hadn’t yet significantly broken. Young Jimmy would have been familiar with him, but ignorant of his true nature. Given that in the film’s present day he is obviously suffering from a sort of arrested development from his childhood trauma, it makes a certain amount of sense that he might emulate a popular celebrity who made a career of appealing to children.

Or possibly just for boys? This much is not, to the best of my recollection, made clear; it’s possible that twenty-eight years into a return to neo-medieval life, the survivors retain a vestige of gender equality, but it would be more in keeping with the film’s Brexit vibe that there’s been a traditionalist retrenchment. I’m only speculating, of course—perhaps we’ll get a more fleshed-out understanding in the upcoming films, but it’s left unclear for the moment.

I will admit: given that the final shot of 28 Weeks Later was infected charging out of the Paris Metro, I found this single line somewhat unconvincing. Part of the point of the first two films is the effective impossibility of containing the virus—hence the quarantine of the British Isles. I’d come into this film assuming that the Rage was now a world-wide catastrophe; I get that the Brexit fable only really works if Britain is isolated from a world that has progressed without it, but it stretches credulity to imagine that the infection could be so easily “pushed back.” Presumably this is what the lamentably unproduced 28 Months Later would have chronicled. Alas for that.

The fact that Ireland is included in this quarantine seems vaguely unfair.

An actual island off Northumbria, where much of the movie was filmed. Also called Lindisfarne.

Add to this the fact that the population of Holy Island is entirely White and one begins to sense an undercurrent of Danny Boyle and Alex Garland taking the piss.

The recitation is a 1915 recording of American actor Taylor Holmes.

This is an observation that goes for post-apocalyptic narratives more broadly. One of the few exceptions is Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2007), which is so unremittingly bleak that the first time I taught it, my class’s reaction was to say “Why don’t they just kill themselves?” That pretty much made eliciting class discussion rather difficult. But The Road is unusual insofar as the scenario McCarthy depicts lacks all the comforts and pleasures of a post-catastrophe world usually present in such stories—not least of which is the excess of stuff to which one can help oneself in the absence of other people.

Not for nothing, but I would argue that The Road is structurally a zombie narrative, if not one in detail—the Man and his son wander a radically depopulated landscape, constantly on alert for and in fear of gangs of survivors who want to eat them.

I am sorely tempted to see the film even though the horror genre is not for me - at the time of "28 Days Later" I wrote for a film journal and participated in a press junket in London, meeting the likes of Cilian Murphy and Danny Boyle. Honestly, I am a chicken so seeing these films was tough but given your introduction I might give it a try - thank you!