I’m ashamed to admit that today, a day of significance in my calendar, almost passed without me noticing. It’s March, and March is one of the busiest months in academia as we approach the end of term. Grading, class prep, more grading … as well as trying to keep to a more-or-less weekly schedule for posting here. Stuff gets easy to miss. But then my wife came into my office and started scanning my bookshelves, looking for a Discworld novel to read. When I asked why, she said, “Because everything is terrible in the world right now, and I need a comfort read. Also, we’re coming up on the tenth anniversary of Sir Terry’s death, aren’t we?”

And there it was. I thought, “Well, now I know what my next post is.” Because I doubt I’d ever have developed the concept of magical humanism without Terry Pratchett and Discworld.1

1. Shaking Hands With Death

On this day in 2015, Terry Pratchett died from complications from Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA), the rare form of Alzheimer’s Disease with which he’d been diagnosed eight years earlier. He was sixty-six years old.

By way of making the sad announcement of his death, his Twitter account (managed by his personal assistant Rob Wilkins) posted three tweets.

Ten years on, I still cannot read those tweets without choking up. The death of a favourite author is always uniquely painful: for one thing, longstanding love of someone’s prose invariably establishes a sense of intimacy and closeness; for another, there also comes the grief of knowing you’ll never again read anything new by the deceased.

But these final tweets were, and remain, a particularly poignant stab to the heart for anybody familiar with Sir Terry’s particular relationship with Death, in fiction and in life.

Death is a recurring character in almost all forty-one of the Discworld novels.2 Often, he is incidental to the story, appearing when somebody dies and guiding them to whatever afterlife they imagine awaits them. But he is also frequently a central character, appearing in such novels as Mort (1987), Reaper Man (1991), Soul Music (1994), Hogfather (1996), and Thief of Time (2001). He appears as a forbidding cliché: tall, skeletal, cowled in night with cold blue light burning in empty eye sockets, armed with the requisite scythe. Appropriately, he rides a pale horse. But beyond these cosmetic elements, Sir Terry’s Death is complex, empathetic, and wryly sardonic. And if not human per se, he is decidedly humane—endlessly fascinated by the feckless mortals from whose coil it is his job to shuffle them.

Death also has a deep love for cats. And his pale horse? He’s named Binky.

Death with a kitten. Art by Paul Kidby.

From the time of his diagnosis in 2008, Sir Terry became an outspoken advocate for right-to-die legislation in the U.K. Though Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) is nominally a universal caregiver, Sir Terry quickly divined that degenerative illnesses comprised a large gap in coverage: the wealthy could pay for expensive treatments at home or avail themselves of such services abroad in order to slow their disease’s progression, but sufferers without means could only look forward to accelerated decline. Though Sir Terry could himself afford the drugs and treatment, he was enraged at the inequity, and with the fact that, whatever his wealth, he was denied the option of ending his life at a time of his choosing, when he was still in enough command of his faculties to bid the world goodbye on his own terms.

His advocacy was boosted by his fame as a writer (he was the best-selling author in the U.K. before Harry Potter received his summons to Hogwarts), but it also borrowed some moral force from his familiarity with Death as imagined in Discworld. In 2010 he delivered the Richard Dimbleby lecture,3 which he titled “Shaking Hands With Death.” In it, he remarked on how Death had evolved to become one of people’s favourite characters in his fiction. This much is appropriate, as it is not Death people fear so much, “they fear the things—the knife, the shipwreck, the illness, the bomb—which precede, by milliseconds if you’re lucky, and many years if you’re not, the moment of death” (“Shaking Hands with Death” 287). Death himself is a simple fact, the terminus that defines our mortality, which in turn defines our humanity. As Sir Terry himself observes, Death “appears to have some sneaking regard and compassion for a race of creatures which to him are as ephemeral as mayflies, but which nevertheless spend their brief lives making rules for the universe and counting the stars” (275).

Sir Terry’s Death is thus something close to a benevolent figure: a guide into whatever afterlife the deceased’s beliefs and conscience create for them. And his pervasive presence throughout the Discworld series produces a thematic iteration on humanity as defined by mortality—which itself produces a thematic iteration on how this relationship defines a moral and ethical humanism. For one of the great allegorical gestures of the Discworld novels is an expansive humanism that extends to cover all sentient beings.

2. The Iterative Discworld

Discworld began as something of a larf, a straight-up parody of “high” fantasy. The first two novels, The Colour of Magic (1983) and The Light Fantastic (1986), are riotously funny, but in truth not very substantive: they essentially take the piss of post-Tolkien fantasy, which by the 1980s was generally derivative of Tolkien’s verbiage and high seriousness, but without the intellectual depth and complexity of The Lord of the Rings. The genre had largely calcified, and Sir Terry, a passionate lover of fantasy and science fiction, showed his love by poking it with a sharp stick. The Discworld was created to be overstated and absurd:

Through the fathomless depths of space swims the star turtle Great A’Tuin, bearing on its back the four giant elephants who carry on their shoulders the mass of the Discworld. A tiny sun and moon spin around them, on a complicated orbit to induce seasons, so probably nowhere else in the multiverse is it sometimes necessary for an elephant to cock a leg to allow the sun to go past … Exactly why this should be may never be known. Possibly the Creator of the universe got bored with all the usual business of axial inclination, albedos and rotational velocities, and decided to have a little fun for once. (Wyrd Sisters 5-6)

The Great A’Tuin bearing the Discworld. Art by Paul Kidby.

The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic are highly entertaining and laugh-out-loud funny, but most devoted Discworld fans will tell newcomers not to start the series with them. Had Sir Terry abandoned Discworld after these early forays, they would be curiosities but not much more. But he came back, again and again, forty-one times—averaging two novels a year from The Light Fantastic until his death. Each novel is a standalone; each gives new detail and substance to the Discworld, and with each iteration the novels develop a moral and political philosophy that I have come to call magical humanism.

But more on that in a moment.

Most Discworld fans tend to recommend that newbies start somewhere in the middle4 when the world-building has become more confident and the Discworld itself has developed a more definite shape and heft. As the series makes its iterative way along, Sir Terry’s storytelling similarly becomes more confident and substantive, not least because he has a more substantive world in which his stories can unfold. The early novels are still working things through: when you read them after familiarizing yourself with the more established Discworld, they appear as early, partly-formed clay sculptures, whose shape is identifiable but lack the nuance and complexity of the later iterations.

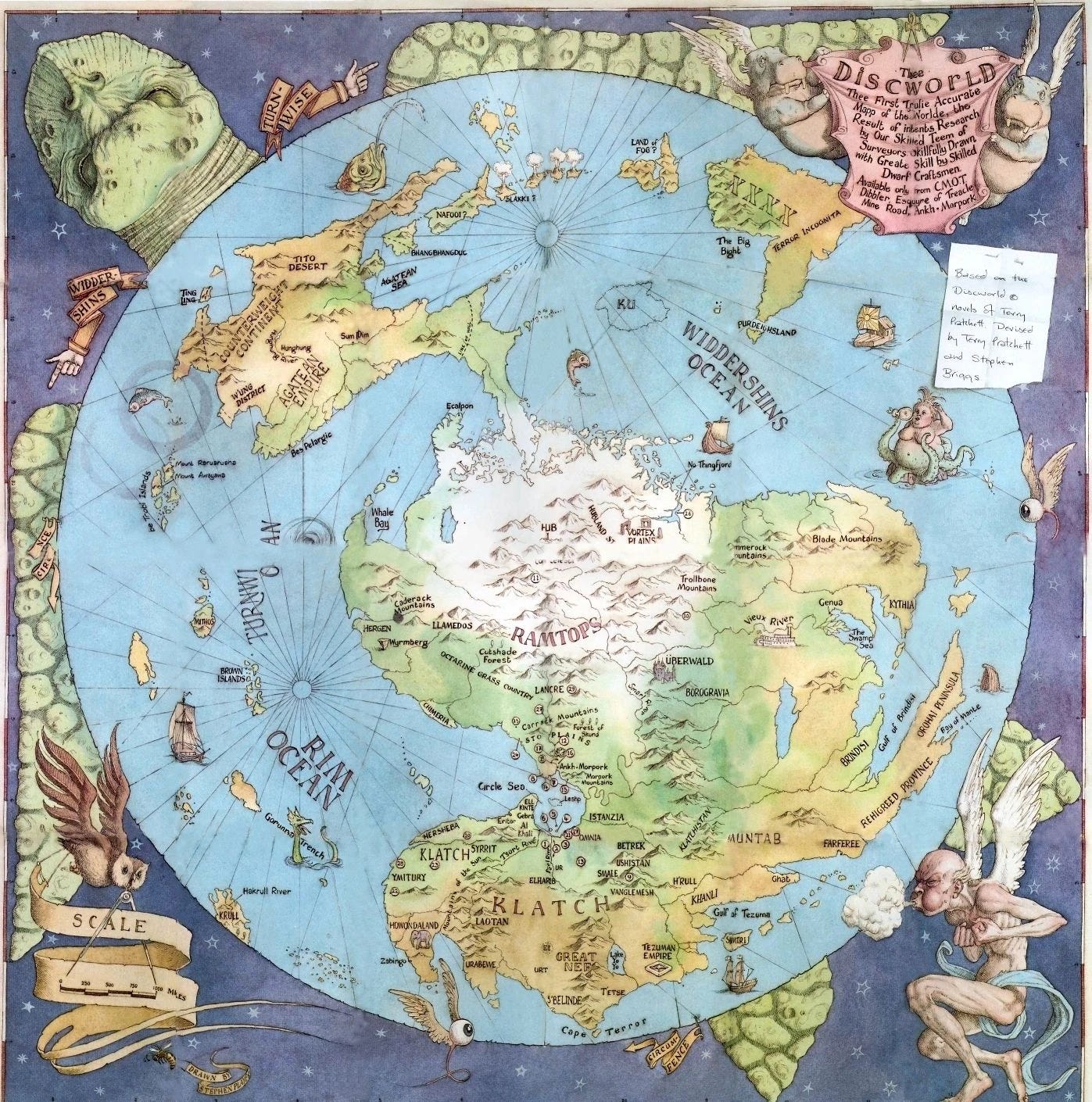

On the other hand, if you start with The Colour of Magic and read the books in the order of their publication, you will have the experience of watching the Discworld take shape, story by story. One thing seasoned fantasy readers will notice is that the Discworld novels do not come with maps, something unusual for the genre.5 Sir Terry resisted this convention for a long time, disliking what he saw as a sort of godlike cheat that shaped territory to be more convenient to the narrative: “I did worry about the ‘map first, then chronicle the saga,’” he writes. “A map should be of something that is, in some material way, already there” (The Discworld Mapp). Drawing the territory “before you actually build the world” he continues, “is the prerogative only of gods.” But when Stephen Briggs approached him in the mid-1990s with the idea of creating an official Discworld map, he presented Sir Terry with his own logic as just articulated—observing that there were, at that point, twenty-odd Discworld novels. With that much material to work with, it would be less a matter of godlike creation than a surveying expedition. “As the novels of the series were produced,” Sir Terry allowed, “it became obvious that the Discworld is now already there.”

This iterative quality of Discworld is, perhaps serendipitously, reflective of the broader sensibility of Sir Terry’s writing and the philosophy that emerges from his novels. There is little that is programmatic about the world-building we see: it comprises its own sort of evolutionary process, which is eminently appropriate to an author whose understanding of humanity celebrated our evolutionary origins. Speaking of his experience reading the Bible and the idea that humans are divinely created, he said,

I find it more interesting—in a sense, more religiously interesting—that a bunch of monkeys got down off trees and stopped arguing long enough to build this, to build that, to build everything. And we’re monkeys! Our heritage is, in times of trouble, to climb trees and throw shit at other trees. And actually, that’s so much more interesting than being fallen angels.6

He went on to offer a sentiment he often repeated, and which appears in his fiction:7 “I’d rather be a rising ape than a falling angel.”

3. Magical Humanism

Fantasy as a genre, as I suggest in our first video, effectively begins with Tolkien.8 “Classic” fantasy—which is to say, Tolkien-inflected fantasy, the kind Sir Terry was poking with a stick—is generally organized along extrinsic principles: prophecy, fate, destiny, and (usually) a Manichaean order of good vs. evil, light vs. dark. The extrinsic in this respect entails a transcendent ordering principle akin to divinity—what Tolkien identifies in “On Fairy-Stories” as an inherently religious sensibility, something we find in mythology. “Something really ‘higher,’” he writes, “is occasionally glimpsed in mythology: Divinity, the right to power (as distinct from its possession), the due of worship; in fact ‘religion’” (76).

Tolkien’s distinction here between the “right to power” versus its mere “possession” is a crucial one, as it figures one conception of power as innate, opposed to lesser manifestations of power that can be grasped, traded, possessed, or lost. We see this dynamic not merely represented in Tolkien’s legendarium, but integral to it: magical power is not something to be developed or learned, but is inherent to a given being’s commensurate place in the racial hierarchies of Arda—From Eru Ilúvatar down through the Valar, Maiar, Eldar, Silvan Elves, though the hierarchy of Men (with the Númenóreans at the top), and the various species of orc comprising the lowest rungs.9 As Tolkien scholar Dimitra Fimi notes, Tolkien’s hierarchy is “an allusion to the medieval ‘Great Chain of Being,’ a powerful visual metaphor that represented a divinely planned hierarchical order, ranking all forms of life according to their proportion of ‘spirit’ and ‘matter’” (141). Even the possession of a magical talisman like the Ring itself cannot shift one from this essentially feudal model: for all Boromir’s might, the best he could have managed was to become a much greater warrior than he already was, more powerful in degree but not in kind, whereas if Gandalf took up the Ring he would supplant Sauron as a new Dark Lord—as befitting his stature as a Maiar.

The most elemental difference between Tolkienesque fantasy and Discworld (and, indeed, a critical mass of contemporary fantasy10) is essentially structural—a basic inversion of this extrinsic ordering logic. The most significant example of what I mean by this is Sir Terry’s reversal of the relationship between the divine and the temporal: gods are not transcendent and eternal, nor do they create the mortals who worship them. Instead, the gods’ existence is predicated on human belief. Which is to say, gods come into existence by way of people’s imaginative leaps of faith, and they gain strength, power, and status in direct proportion to the strength and fervour of people’s belief. By the same token, gods can wither and fade when that belief ebbs, or, in the case of Small Gods (1992), becomes corrupted into unthinking instrumentalist doctrine (the formerly Great God Om starts the novel so diminished that he is trapped in the body of a lowly tortoise).

This contingent nature of the Discworld gods exemplifies how Sir Terry allegorizes the mechanisms of reality-building. Gods existing as a function of people’s beliefs rather than as an eternal, transcendent Real stands in for the innumerable little concrete realities governing our lives that are, in fact, collective consensual hallucinations: currency, national borders, place names, jurisprudence, constitutional democracy, and so on.

Similarly, the contingent nature of the Discworld gods applies also to the peoples of the Discworld. The hierarchies that proceed from the Great Chain of Being are shattered by the displacement of the divine: if gods are dependent on mortals for their power, status, and very existence, how then does one fashion hierarchies of being whose logic is predicated on proximity to godliness? Which isn’t to say there aren’t many instances of prejudice and the ideation of racial/species supremacism—the eternal argument between dwarfs and trolls is alive and well in Discworld—but rather that such bigotries and biases comprise the substance of conflicts that drive many of the Discworld narratives. Other races and species in Sir Terry’s legendarium aren’t Other but instead facets of a capacious understanding of the human.

When speaking or writing about Sir Terry, I will usually say that his work is “profoundly humanist.” I am however always compelled to follow that assertion with a laundry-list of caveats about what that doesn’t mean. I consider myself a humanist—I am, after all, a humanities professor—but given humanism’s fraught history as a concept and a practice, this necessitates a certain amount of qualification. Without rehearsing a history of the term, suffice to say its fraughtness (fraughticity?) historically proceeds from delineating the Human as a rigid category—which has inevitably tended to draw a bright exclusionary line around who qualifies.11

Sir Terry’s humanism (and mine) is the small-h variety, which also, ideally, stands for humility. Which is to say: a humanism that is not categorical or exclusionary. In Discworld, though humans are just one species among the many that comprise fantasy’s legendarium—dwarfs, trolls, pixies, golems, goblins, orcs, vampires, werewolves, gnomes, and elves, among others—the word “human” functions as a catchall, synonymous with “mortal” or, more plainly, people, among whom there is none inherently good or inherently evil. As John Seavey observes, as the Discworld novels progressed they became increasingly preoccupied with “redressing issues long swept under the rug by a parade of Tolkien successors,” not least of which is the way in which much of the genre created enemies in the mold of Tolkien’s orcs, unequivocally evil beings whose purpose is little more than to be an expendable “notch on the protagonist’s sword.” Pratchett engages with the discomforting question of such species’ humanity, who otherwise tend to be useful undifferentiated cannon fodder in the armies of the genre’s ubiquitous Dark Lords. Seavey frames the question: “If goblins and orcs and trolls could think, then why were they always just there to be slaughtered by the heroes? And if the heroes slaughtered sentient beings en masse, how heroic exactly were they?”12 Seavey’s question resonates with the simple but profound wisdom of Sir Terry’s great witch Granny Weatherwax, who asserts that the root of evil is when we start to see people as things.13

Magical humanism in this respect, then, is to humanism what magical realism is to realism. The “magic” in both instances isn’t necessarily anything supernatural, but the recognition that huge swathes of “reality” are in fact imaginary. Sir Terry opined on more than a few occasions that “Imagination, not intelligence, made us human.” Though one could reasonably argue that this is a distinction without a difference—that you can’t have the former without the latter—it is the imagination that is more consonant with our emotional being, and thus what makes us irreducibly messy and innately absurd and silly creatures.

Human, in other words.

4. What We’ve Lost

It’s difficult to believe it’s been ten years. The death of Sir Terry is grievous to me not just because I’ll never again read a new Discworld novel. It’s grievous because I feel keenly the absence of his mind—his mischievous, hilarious, blisteringly intelligent, empathetic, and profoundly human mind. We are all the poorer for his absence, for we lack the comfort of knowing there’s a bulwark against the stupidity and cruelty of the world.14

Sir Terry died before Brexit; he died before the election of Trump; he died before a flawed world tipped over into the absurdity of whatever we want to call our current odious stew. One can only imagine what he would have thought of the antics of Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, of the ascendancy of tech billionaires and their pretensions to world domination, of America’s doubling-down on Trump 2.0. That we lack his humour and rage and his capacity to imagine for us an alternative world is a profound loss. I don’t begrudge him his rest, but I weep for a world without his wisdom.

My wife’s impulse to reach for a Discworld novel in the present moment is, to my mind, an act of the most utter sanity.

REFERENCES

Fimi, Dimitra. Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits. Palgrave, 2010.

Pratchett, Terry and Stephen Briggs. The Discworld Mapp: Being the Onlie True and Mostlie Accurate Mappe of the Fantastyk & Magical Dyscworlde. Corgi, 1995.

Pratchett, Terry. “Shaking Hands With Death.” A Slip of the Keyboard.

---. Hogfather. Corgi, 1996.

---. Small Gods. Corgi, 1992.

---. Wyrd Sisters. Corgi, 1988.

Seavey, John. “The Evolution of the Disc.” MightyGodKing Dot Com, 10 January 2010, https://mightygodking.com/2016/01/10/the-evolution-of-the-disc/.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-Stories.” Tree and Leaf. Harper Collins, 2001. 1-82.

NOTES

A few paragraphs of this essay have been adapted from sections of an essay I posted to Medium July 1, 2023, “Sir Terry vs. the Gender Auditors.” I will at some point in the future be rewriting and revising that essay and posting it to The Magical Humanist.

All but two: The Wee Free Men (2003), and Snuff (2011).

Actually, he didn’t deliver it. He wrote it, but by then his “embuggerance” had progressed to the point where public speaking was not possible. So he sat and watched as his lecture was delivered by his “stunt Terry”—his friend, actor Tony Robinson, who is perhaps best known for playing Baldrick in Blackadder.

Everybody has their favourite points of entry. It helps to know that, while the novels are all standalone narratives, they tend to fall into clusters with their own arcs. There are the Rincewind novels, featuring a hapless wizard who in spite of his cowardice and antipathy to adventure ends up traipsing all over the Discworld, usually running away from things (he is the protagonist, loosely speaking, of The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic). There are also the City Watch novels, set in the city of Ankh-Morpork, featuring the hard-bitten Watch Commander Samuel Vimes and his collection of misfit watchmen (and -women, and -dwarfs, and -trolls, and so on); these tend to be, generically speaking, mystery narratives. We also have the witches novels, featuring the trio of Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, and Magrit Garlick; as mentioned above, Death also features as the main character in a cluster of novels; Sir Terry also wrote a handful of young adult Discworld novels, centered on the character of Tiffany Aching, a fledgeling witch; and in the later novels he explored the development of new technologies in his fantasy setting, alternately called the Industrial Revolution or Moist von Lipwig novels. There are a handful of fan-created schemas mapping out the thematic clusters, such as this one.

For what it’s worth, my usual suggestions for starting Discworld are Men At Arms (1993), the second City Watch novel; Small Gods (1992), a standalone not belonging to any particular cluster, but which is an excellent introduction to Sir Terry’s cosmology; Wyrd Sisters (1988) is about the earliest novel I’d recommend, and is a great introduction to the witches (though my personal favourite witches novel is Witches Abroad [1991]). Soul Music (1994) is a good Death novel and has the added bonus of being an exemplar of Sir Terry’s sense of humour.

Indeed, one of the reasons I came to Discworld fairly late in the game—I read my first (Small Gods) in 2008—was because their lack of a map was a non-starter for me for a long time. I’m the reader who obsessively flips to the map to get a sense of where the action is happening; when I first read The Lord of the Rings, I was making my own fantasy maps before I wrote my own terrible, terribly derivative, imitations of Tolkien.

Spoken at an interview in front of a live audience hosted by The Guardian.

Specifically, a version of it appears toward the end of Hogfather. Death identifies the human condition as being in “THE PLACE WHERE THE FALLING ANGEL MEETS THE RISING APE” (433).

By “genre” I don’t mean literary genres so much as genre as understood by booksellers, publishers, and authors.

This is a simplified list which does not account for dwarves, hobbits, and Ents. For a more thorough consideration of the hierarchical elements of Tolkien’s legendarium, see Dimitra Fimi’s excellent book Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History.

I find myself building out the Magical Humanist project in the present moment because of an idle though I had many years that became something of an obsession: how did a genre that has its roots in what is an elementally Christian cosmology—Tolkien’s medieval Catholicism, C.S. Lewis’ Christian allegory, and the myth and medieval romance that comprised the basis of their source material—come around to expressing predominantly secular worldviews? Not every fantasy writer of the past two or three decades exemplifies this shift, of course, but we have arrived at a critical mass that does. George R.R. Martin, R.F. Kuang, Lev Grossman, N.K. Jemisin, Philip Pullman, Marlon James, and many others in various ways embody this paradigm shift. (Until recently I would have placed Neil Gaiman quite centrally on this list, and possibly will again in the future, but for the present moment I tactfully elide him—as difficult as that is given his friendship and collaboration with Sir Terry.)

There are too numerous examples to list, but the most obvious is the rise of pseudo-scientific “race theory” in the 19th century and the putatively rational arguments justifying chattel slavery. Especially in the U.S., the legacy of humanism becomes almost paradoxical, both providing the language of inalienable human rights and the rhetorical mechanisms by which to exclude enslaved Africans, i.e. by drawing that bright line around a constructed concept of whiteness.

It is worth noting that one of the great glaring absences from the Discworld novels, in terms of the usual staples of the fantasy genre, is spectacular, large-scale battles. Not only are such military actions absent, but a few of the novels—Jingo (1997) and Monstrous Regiment (2003) most notably—pivot around avoiding armed clashes.

This is neither here nor there, but of the various bits of fantasy casting I’ve imagined for the principal Discworld characters, my one bedrock, unalterable stipulation is that Maggie Smith must play Granny Weatherwax, Miriam Margolyes is Nanny Ogg, and Phoebe Waller-Bridge is Magrit Garlick. Fight me. This is the hill I die on.

Others in this category include Ursula K. Le Guin, Anthony Bourdain, Toni Morrison, and David Bowie. May their memories be a blessing.

Lovely to see my book cited here!

Sadly I came to series too late, but I’m glad I came to it.