It was, in hindsight, serendipitous—one might even call it uncanny—that Tim Walz broke through to national attention by calling MAGAsphere “weird” right around the time I was eyeballs-deep in writing a conference paper on weird fiction.

In late July I attended for the first time the biennial conference of the International Gothic Association, held this year at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax. My paper was on H.P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft is an author I’ve come to pay a fair bit of scholarly attention to in recent years; this winter will be the fourth time I’ve taught a course on the American Weird. Suffice to say that part of my paper was preoccupied with interrogating the concept of the weird, which made it, um—strange? odd? peculiar? unusual?—when suddenly my various news feeds were filled with Walz and others hurling weird as an epithet at Donald Trump and J.D. Vance and their lot. Stranger still was the fact that it seemed to have purchase, getting under their skin in a way little else had done.

It was strange, and strangely satisfying, to watch the MAGAsphere melt down over being called weird. Who knew that that simple insult, which in so many other contexts isn’t an insult at all, would find the traction the vast majority of other attacks hadn’t had? On reflection, it perhaps shouldn’t be that odd—we know from history that the one thing authoritarian types can’t deal with is ridicule and laughter. More to the point is that however unusual, peculiar, and downright bizarre Trumpism and its constellation of fellow travellers can be, it’s a point of faith for them that not only are they the normal ones, they’re the yardstick by which normality is measured. They are, variously, the “real” Americans and the default setting for normative identity (racially, geographically, culturally, gender-wise, etc.); “Make America Great Again” is a vague but powerful appeal to an imagined past when that normative identity—venerating whiteness and rigidly defined conceptions of masculinity and femininity—was unquestioned.

Possibly my reader will glean from my preceding paragraphs how difficult it is to avoid using the word “weird” except by way of introducing my topic. I have to reach for workable synonyms. Strange, odd, unusual, peculiar, bizarre … my instinct is to default to “weird” almost every time, and resisting that instinct is an instructive exercise.

But then, “weird” is a catch-all—we use it ubiquitously, and its inflections depend on context. “You are so WEIRD,” spoken in a scathing tone by a mean girl is light years away from saying goodbye with “Stay weird!” The MAGAsphere’s pained response was appropriately juvenile, given that it perceived the former inflection, which tells them they’re uncool1—which is to say, unsuccessful in conforming to the standards of an acceptable normalcy. “Stay weird” by contrast congratulates its subject for being nonconformist and, more likely, being indifferent to people’s judgments of them. This rhetoric of weirdness as directed at Trump et al was, well, weird precisely because the vast majority of those who employed it as a pejorative would likely not themselves be bothered to be called weird—would, more likely, take it as a compliment, or take satisfaction in knowing something about them had irked the self-appointed arbiters of normality.

But what does this have to do with Lovecraft? In one sense, nothing—just a serendipitous convergence.

But then, serendipity is my favourite imaginative catalyst, and it got me thinking. And the more I thought about it, the more I found uncanny resonances between the Lovecraftian Weird and the Trumpian Weird. I noodled about with the idea for the rest of the summer, then backburnered it when classes started in September. As the term went on and the election campaign raged, the Harris camp stopped calling Trump at al weird, which I thought was a tactical error. Still: however much I reminded myself that the election was a toss-up, I now realize I never really let myself believe Trump would win. And so when at various moments I returned to my notes for this essay, my sense was that I had missed its moment and that going forward, were I to write it, it would be a curiosity at best.

Welp. So much for that. Trump’s win and all that it presages for the next four years makes this topic terribly relevant all over again. To be certain, that’s cold comfort at best; better that this would have been a relic of a fleeting moment.

A QUICK READER’S GUIDE: I’ve been working on this for a while now, and it has grown in the telling. So I’ve broken it down into three sections, in which (1) I offer a working definition of the Weird, historically and etymologically, and then how Lovecraft adapts it; (2) I dig into Lovecraft’s more odious qualities—most specifically, his racism—and how that is integral to his particular development of a Weird aesthetic; and (3) I go back to the weirdness of Trump and MAGA.

So if you’re quite well versed in the Weird, you may want to skip section one; if you’re similarly familiar with Lovecraft’s racism, you can also fast forward to section three; and if you don’t care about the Trumpian Weird … well, I’m at a loss as to why you’re still reading this. Peace out and go with the Elder God of your choice.

Otherwise … are you sitting comfortably? Then we’ll begin!

1. The Weird, (sort of) Defined

Weird’s most common colloquial use, “strange or unusual,”2 is relatively recent—it only started being used in that sense in the early 19th century. Prior to that it was associated with the supernatural, specifically in reference to fate and destiny. In fact, the earliest use of “weird” was not as adjective, but noun, literally meaning fate.3 One of the references in the Oxford English Dictionary quotes Beowulf: the titular character says "gaéð á wyrd swá hío scel,” which translates to “Fate shall go as she will.” It becomes adjectival in the early modern period, most famously in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, in which the three witches4 whose prophecies predict (or possibly precipitate) the action are referred to as the “weird sisters.”5

The OED shows us the transformation of the term, from fate and destiny, to “having the … supernatural power of dealing with fate or destiny,” to “Partaking of or suggestive of the supernatural.” This latter definition goes on to add “unaccountably or uncomfortably strange; uncanny,” which perhaps signals how the word migrates to the more quotidian “strange or unusual,” which is where we started.

For our purposes, weird’s oracular origins are significant. For what is weirdness, even in its most banal forms, if not a funhouse mirror reflecting “normality” in skewed but elucidating ways? Arriving at an understanding of what is “weird” is a normative exercise, as it raises the question of why is something weird, and by what metric do we circumscribe the normal? How does designating something weird offer critique on a putative normality?

By this token, the etymology of “weird” is similar to that of “monster,” which, in addition to being associated with horror and the uncanny, also has oracular overtones to its etymology. The Latin monstrum means both “monstrous creature, wicked person,” but also “Portent, prodigy” (OED). It shares a root with monere, which means, variously, to warn, to teach, or to foretell.6 All of which is appropriate when you consider that monsters almost invariably reveal something to us, articulating fears and anxieties that are usually specific to the cultural moment—whether it’s giant irradiated ants manifesting nuclear paranoia in 1950s B-movies, or our ubiquitous zombies expressing ambivalence to mass culture and consumerism.7 Unsurprising, then, that monsters and monstrosity are key elements of weird fiction.

I suppose I should qualify that statement: monsters and monstrosity are often key elements of weird fiction. It’s not a genre with which one can be categorical: as Ann and Jeff Vandermeer wryly note in the introduction to their mammoth collection8 The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories, “an impulse exists among the more rigid taxonomists to find the Weird suspect” (xvi). The Weird, they say, tends to be indeterminate, not least because it “often exists in the interstices” and “can occupy different territories simultaneously.” Indeed, they suggest, “The Weird is as much a sensation as it is a mode of writing”—not so much I know it when I see it as I know it when I feel it. This much Lovecraft himself asserted in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” stipulating that “A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread” (107) is necessary.

The indeterminacy of the Weird as a genre mirrors the way in which indeterminacy is perhaps the one constant in its fictional iterations.9 Lovecraft himself marks out the weird largely by what it is not: “The true weird tale,” he says, “has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains” (107). The “unexplained dread” cited above is the dread of “outer, unknown forces,” which in Lovecraft’s most significant stories10 comprise the unthinkable eldritch11 of such “old gods” as Cthulhu and Nyarlathotep (among others). Lovecraft’s particular territory within the nebulous landscape of the Weird is what has come to be called “cosmic horror,” which operates predominantly by way of profound existential dread rather than acute terror. The particular weirdness at work in cosmic horror—the sensation, as the Vandermeers have it—is one of uncanny dislocation from the known and familiar, but on a titanic scale. Lovecraft’s introductory paragraph in “The Call of Cthulhu” works as a mission statement in this respect:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age. (139)

The problem Lovecraft sets for himself is one of representation: if the horror at the heart of cosmic horror is our own infinitesimal insignificance in the face of an eldritch cosmos too vast and terrible for our puny minds to comprehend, how does one depict that in a language that is necessarily as limited as our stunted intellects? How, in other words, does one speak the unspeakable?

Short answer: by imagining monstrous beings that function as a shorthand for the unspeakable—a sort of monstrous metonymy, if you like.

Lovecraft’s cosmic horror finds its distillation in the “Cthulhu Mythos,” so named for the tentacular old god who has become synonymous with Lovecraft’s fiction and world-building. Cthulhu is in many ways the embodiment of the Lovecraftian Weird: “of a form which only a diseased fancy could conceive,” Cthulhu is chimerical, conflating “an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature … A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings” (141).

Cthulhu as rendered by artist Andrée Wallin.

There are a few details here to bear in mind going forward, not least of which is the straightforward revulsion we’re meant to experience with that description. Of particular note is the tentacle, which, as China Miéville notes in his introduction to the Modern Library edition of At the Mountains of Madness, is “a limb type largely missing from western mythology” whose appearance in Lovecraft and other practitioners of the Weird is “symptomatic of [a] sea change in the conceptualization of monsters” (xiv). More to the point, it exemplifies a sort of aquatic abjection central to Lovecraft’s monstrous figurations, with the adjectives “pulpy” and “scaly” emphasizing the profound Otherness of fishy, watery beings. I have had many occasions to idly speculate on whether Lovecraft was himself hydrophobic, or whether he just had a good instinct for what we landlubbers find repellent. One way or another, seas and oceans never portend anything good in Lovecraft’s fiction, and the waters’ various points of contact with land—especially in such liminal spaces as swamps and reefs and raised seabeds—tend to be where the worst things go down. As I joked in my Gothic Association conference paper, Lovecraft provides an answer to one of the Scarecrow’s musings in The Wizard of Oz. Why, he wonders, is the ocean near the shore? Because, Cthulhu whispers from beneath the surf, it’s where the eldritch brings madness to oblivious landbound mortals.

(I did not get a laugh).

2. Lovecraft’s Racist Metonymies

As I mentioned above, I’ve been preoccupied with Lovecraft and weird fiction for a number of years now;12 it started as a side quest from my other two principal scholarly interests in contemporary American literature and science fiction and fantasy. Given its overlap with both of those fields, it’s become something of a bridge between them, and thus something of a main quest in its own right.13

Lovecraft remains something of a curiosity in the broader context of my interests, insofar as he’s a writer to whom I devote a lot of time and thought, while also profoundly disliking his writing. The fascinating question Lovecraft poses for me is just why he continues to be so influential when he was on one hand an objectively terrible writer,14 and on the other … well …

To repurpose Dickens’ opening of A Christmas Carol: Lovecraft was racist, to begin with. There can be no doubt whatever about that. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate.

It also needs to be understood that Lovecraft’s racism wasn’t merely an expression of systemic social mores. As Miéville observes, one apologia often offered is “that it was ‘the Time’—people were just ‘like that’ back then” (xviii). I have indeed fielded such defences from students when I’ve taught Lovecraft, saying we can’t judge him by contemporary standards. I generally respond much as Miéville does, saying “This is an unacceptable condescension to history: people were emphatically not all like that.” Lovecraft’s racism was not unusual, but it was hardly unthinking—his was the kind of racism one must work at, devoting a lot of thought and energy to creating an intellectual armature for white supremacy. His voluminous correspondence makes clear the mental work he devoted to this effort. To again quote Miéville, who does not mince words:

His idiot and disgraceful pronouncements on racial themes range from pompous pseudoscience—“The Negro is fundamentally the biologically inferior of all White and even Mongolian races”—to monstrous endorsements—“[Hitler’s] vision is . . . romantic and immature . . . yet that cannot blind us to the honest rightness of the man’s basic urge . . . I know he’s a clown, but by God, I like the boy!”15 This was written before the Holocaust, but Hitler’s attitudes were no secret, and the terrible threat he represented was stressed by many. (Lovecraft’s letter was written some months after Hitler had become chancellor.) So while Lovecraft is not here overtly supporting genocide, he is hardly off the hook. (xviii)

Another apologia sometimes offered is that, sure, Lovecraft was hella racist and antisemitic, but his fiction is something else entirely, and we need not obsess over his unfortunate misguided beliefs when considering his art.

As will become clear momentarily, I find this particular notion disingenuous to the point of delusion.

To return to a point I was making in the previous section: Cthulhu and his cohort function as a sort of shorthand or cipher for the unrepresentable. Lovecraft’s monsters thus function metonymically, visible fragments of an eldritch totality that remains unseen, but whose hints are horrifying enough in and of themselves to send those who brush up against them shrieking into madness or death. But Lovecraft was also savvy enough to realize that such horrors are most effective when used sparingly—as anybody who has seen a J.J. Abrams monster movie knows, the fright factor all but dissolves once the monster is revealed in its totality. His stories thus tend to proceed by hints and suggestion; the monstrosity of the hidden eldritch reality is suggested by the monstrosity of the human beings who are either most susceptible to it or who actively submit to its malevolent power.

And just which human beings are most susceptible or eager to so subsume themselves? Those whom for Lovecraft are less than human.

One story that exemplifies what I’m talking about is “The Horror at Red Hook,” generally agreed to be the most racist story in a corpus that is rarely coy in its racial animus. As such, it tends to be ignored, discounted, or dismissed by Lovecraft’s critical apologists—treated much as his racism itself is often treated, as unfortunate but somehow ancillary to his greater vision. I am arguing the opposite: it is in fact integral, and “The Horror at Red Hook” effectively functions as a sort of Lovecraftian decoder ring in this respect.

Lovecraft describes Red Hook as “a maze of hybrid squalor near the ancient waterfront opposite Governor’s Island” (119). It is inhabited by:

a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and negro elements impinging upon one another … It is a babel of sound and filth, and sends out strange cries to answer the lapping of oily waves at its grimy piers and the monstrous organ litanies of the harbour whistles. (119)

From this “tangle of spiritual putrescence the blasphemies of an hundred dialects assail the sky” (120), and out of windows peer “swarthy, sin-pitted faces.” Crime, of course, is rampant, ranging from “diverse styles of lawlessness and obscure vice to murder and mutilation in their most abstract guises.” The police, Lovecraft laments, have long since given up any hope of bringing order and instead “erect barriers protecting the outside world from the contagion.” That Lovecraft employs “contagion” to characterize the nonwhite population of Red Hook is unsurprising—he was, among his other traits, a eugenics enthusiast—but it is particularly germane insofar as the horror of Lovecraft’s Weird is ultimately rooted in the fear of the self as not inviolable, but permeable and liminal.

What makes “Red Hook” particularly useful is that it makes explicit the intrinsic relationship between three elements: the ineffable, existential terror that comprises the “cosmic” aspect of cosmic horror; the figurations of abjection and revulsion in which that terror manifests itself; and the rigidly drawn hierarchies of race that underwrite the structure of the Lovecraftian mythos. “The Horror at Red Hook” makes plain a racial dynamic integral to the mythos, in which nonwhite people exist in the liminal space between rational, virtuous (i.e white) normality, and the howling void of the “black seas of infinity” (to again quote the opening of “Cthulhu”). Lovecraft’s figuration of nonwhite peoples as more susceptible to corruption by the supernatural is predicated on his assertion that they are savage and primal, and indeed not entirely human.

In “The Call of Cthulhu,” the dreams of the titular Old God, slumbering in his drowned city of R’lyeh, infect certain kinds of people and give rise to “Cthulhu cults” and other manifestations of eldritch mania. Those susceptible to these oneiric emanations are themselves liminal: people of artistic temperaments, the mad and insane, and of course the putatively savage. When Cthulhu is disturbed in his sleep, these “sensitives” have episodes in which artistic types find themselves (for example) sculpting tentacular horrors, and insane asylums experience riots by the inmates. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lovecraft is most extensive and detailed in describing the effects on the third category of sensitives:

[I]tems from India speak guardedly of serious native unrest … Voodoo orgies multiply in Haiti, and African outposts report ominous mutterings. American officers in the Philippines find certain tribes bothersome about this time, and New York policemen are mobbed by hysterical Levantines … The west of Ireland, too, is full of wild rumour and legendry. (146)

By contrast, upstanding, rational white people, characterized as “Average people in society and business—New England’s traditional ‘salt of the earth’” (145), are unaffected, except in instances of direct contact with the supernatural—or, more nefariously, when they people actively seek out the dark arts for their own enlargement. The villain of the piece in “The Horror at Red Hook” is Robert Suydam, a venerable scion of Dutch stock. Suydam is not merely corrupted but dangerous, bringing as he does a white man’s intellect and mastery to bear on the otherwise inchoate forces of necromancy and magic. Like Gandalf with the One Ring, his higher place in the Great Chain of Being means he potentially wields far greater power than a lesser mortal could ever hope to—something making plain (or more plain) a racial hierarchy built into the mythos’ foundation.16

3. The Trumpian Weird

Which brings us back to where I started: the weirdness of Trump, and the Trumpian Weird. My epiphany this summer when I first started down this rabbit hole was that it made perfect sense to view the MAGAsphere through a Lovecraftian lens. Lovecraft’s Weird is dystopian—imagining the spectre of humanity’s insignificance, but beyond that existential terror, his fiction unfolds as a series of incursions by the weird into the normal, infecting his characters’ sanity and sometimes (as with “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”) their bodily selves. The principal reason why it’s simply wrong to assert that Lovecraft’s personal racism and his fiction are separate and distinct is because his fictional project was devoted to drawing bright lines around an idealized white subjectivity. The existential horrors of his mythos might proceed from humanity’s insignificance in the face of the infinite, but it was practically effected in his stories by the fear that that white subjectivity might be violated.

Trumpism and MAGA and all the variations on their themes function by way of nostalgic appeals to just such a white subjectivity, tacitly framed as the elemental and authentic reality of America. In their speeches at the Republican National Convention this summer, both J.D. Vance and Tucker Carlson explicitly rejected the understanding of America as an “idea,” in favour of something far less contingent. Vance allows that “a lot of brilliant ideas” went into the creation of the U.S., but in the end it’s a nation, which means it’s a “people with a shared history and a common future”—which doesn’t seem too far beyond the pale, but is at odds with the famous stipulation by John Adams saying precisely the opposite, that the U.S. was “a government of laws, not men.” Carlson goes a step further in his valorisation of Donald Trump, identifying something elemental that goes beyond, or beneath, the constitutional armature granting presidential power. For Carlson,

I can call my dog the CEO of Hewlett-Packard, it doesn’t mean she is. It’s true. And you hate to say it, but it is also true, is a fact, that you could take, I don’t know, a mannequin, a dead person, and make him president … But being a leader is very different. It’s not a title, it’s organic. You can’t name someone a leader. A leader is the bravest man. That’s who the leader is. That is true in all human organizations. This is a law of nature.

In hindsight, it should have been no surprise that Tim Walz’s charge that the Trumpian cohort was just weird would bother them so much. When the innate leadership of Trump is a “law of nature,” that makes it the antithesis of the weird (no matter how weird the RNC’s spectacle was). Weirdness, after all, is what the MAGAsphere sees itself arrayed against: the existential threat they see as embodied by immigrants “polluting” the body politic, by queer and trans folk, by women seeking to upend patriarchal authority, by the “woke” and their temerity in pointing out America’s systemic racism and fraught history … the list could go on, ad nauseum.

I mentioned earlier that one of the questions I find most fascinating about Lovecraft is why such a terrible, racist writer still has such purchase on the contemporary imagination? But if you’ve read this far, it should be hopefully obvious why this question is more than a little disingenuous. In a world beset by enormities, the existential dread of Cthulhu is perfectly comprehensible to us.

These “enormities” of the present day are akin what philosopher Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects,” namely “things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans” (1). For my purposes here (for reasons that will be clear momentarily), I modify this slightly to mean massive entities that are at once omnipresent and inescapable, and yet intangible and invisible.17 Two examples appropriate to my broader theme here are petrocultures and social media. In the first, fossil fuels are the very basis for present day civilization, at once making possible the material existence of almost everything we do, while also shaping culture and society to its needs. Everything we do all day every day, from our ubiquitous plastics, to transportation, to heat and electricity, is inflected by oil and its cousin carbons. And yet it is easy to ignore it unless you are motivated not to.

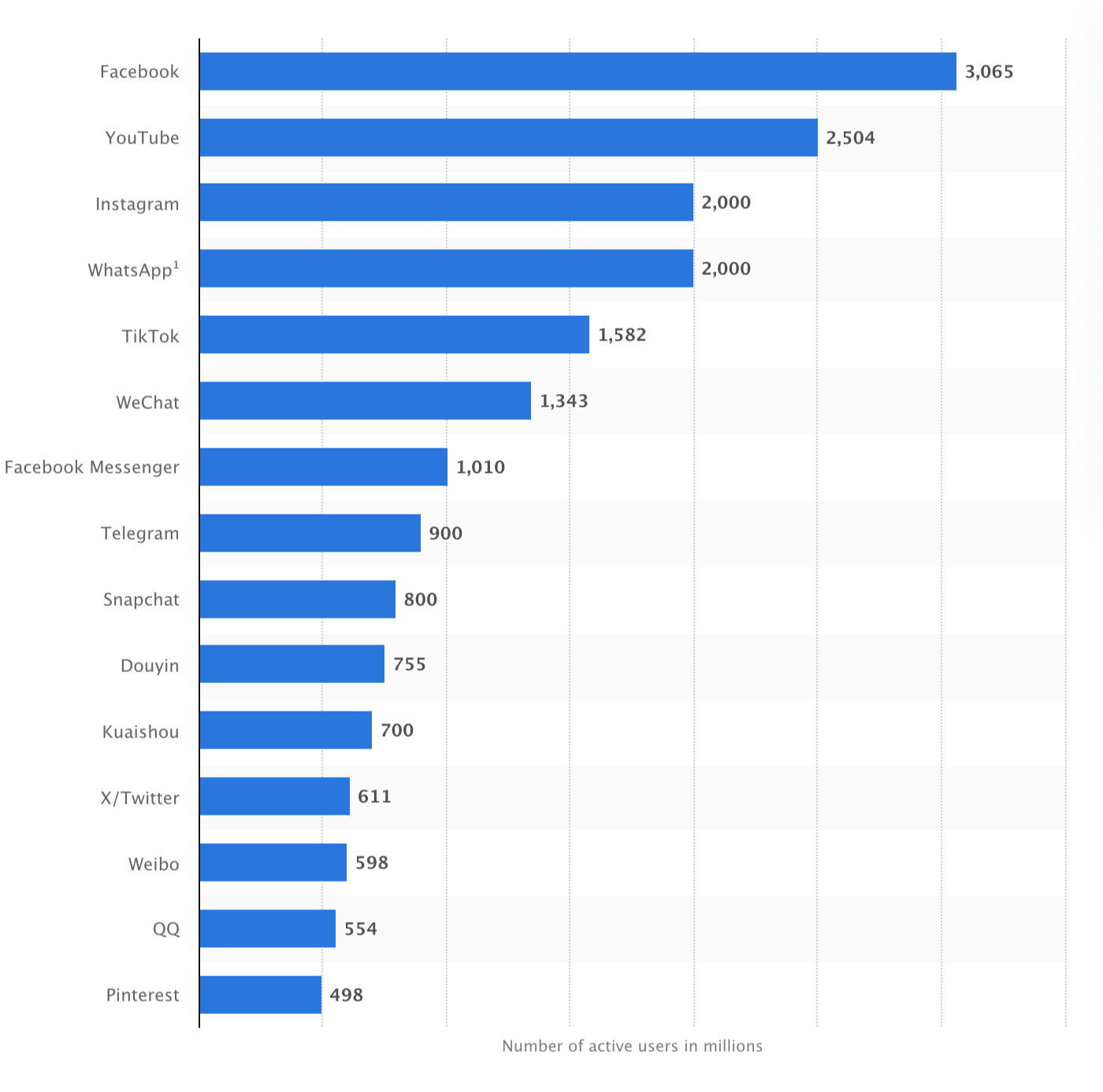

In the second example, social media is a similar omnipresence, operating on an unthinkably vast scale, with over three billion people using Facebook alone.18 The deleterious effects of algorithmic social media have been chronicled now in numerous books and studies (some by the platforms themselves); the presence of a critical mass of social media and tech CEOs on the dais at Trump’s inauguration is as profound a symbol as any for the power and influence wielded by digital platforms. And yet social media is a non-entity, existing in the nonspace of virtuality.

So: it makes a certain sense that Lovecraft’s mythos and its paranoid preoccupation with a malevolent infinitude that remains invisible to most and can be perceived only in hints and fragments by an unfortunate few would resonate with our present moment. And indeed, as I mention above, there’s a conspiratorial element to the mythos, which also resonates: when we think about the Trumpian Weird, we have to address the fever dreams of QAnon, or the figuration of a Leviathan-like Deep State, or the broader way in which conspiratorial thinking has just become an inescapable Masonic grammar.

I had intended to conclude this essay on a hopeful note, discussing a variety of texts that repurpose Lovecraft’s mythos toward productive, progressive, and even at times utopian ends. The Trumpian Weird is at odds with these perspectives, what we might call the adaptive, or perhaps inclusive, Weird. Given how long this essay has gone on, however, I will save that for a future post.

***

I’m posting this on the day of the inauguration, and I personally feel at a very low ebb. I hope my words find everybody taking comfort in those parts of your life that give you hope.

REFERENCES

Houellebecq, Michel. H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. Trans. Dorna Khazeni. Cernunnos, 2019.

Lovecraft, H.P. At The Mountains of Madness. Modern Library, 2005.

---. “Supernatural Horror in Literature.” At the Mountains of Madness. 105-173.

---. “The Call of Cthulhu.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S.T. Joshi. Penguin, 1999. 139-169

---. “The Horror at Red Hook.” The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S.T. Joshi. Penguin, 2004.

Miéville, China. “Introduction.” At The Mountains of Madness. xi-xxv.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

Vandermeer, Ann and Jeff (eds). The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. Tor, 2012.

NOTES

“Cool,” like “weird,” being a designation dependent on context.

“Of strange or unusual appearance, odd-looking” (OED).

“The principle, power, or agency by which events are predetermined; fate, destiny” (OED).

Interesting fact: though the paratext of the play refers to them as “First Witch,” “Second Witch,” and “Third Witch,” the actual word witch is only used twice—both times by the witches themselves. Macbeth refers at one point to “witchcraft,” but otherwise the three prophetic women are always called the “weird sisters” or “weird women.”

Technically, they are called “weyward” or “weyard.” That at least is how the word is variously spelled in the First Folio. The OED tells us “The evolution of the forms found in Shakespeare's Macbeth was apparently from weyrd to weyard (retained in Acts iii and iv in the First Folio) and weyward (used in Acts i and ii); the latter was no doubt due to association with wayward, a word used many times by Shakespeare. (The later folios retain the weyward spelling, and alter the other to this or to wizard.) In several passages the prosody clearly requires the word to be pronounced as two syllables.”

We helpfully find the intersection of the monstrous and the weird in Macbeth, and also in Julius Caesar. Both plays feature soothsayers of a sort, and in both plays the “death princes” is prophesied in massive storms, within which emerge “prodigies” whose monstrous appearances foretell monstrous actions.

To be clear, zombies are about a lot of things. My own reading is that they’re the revolt both by and against mass culture, but that’s not an interpretation I offer to the exclusion of others.

Seriously: it’s a massive book. I ordered it and when it arrived I was momentarily baffled by the size and weight of the box, trying to remember what I’d recently ordered online and what could be this heavy. Suffice to say, it’s not a book you can read in bed or drop in your bag to read on the bus. On the other hand, it can certainly double as a weapon for hand-to-hand combat.

There’s probably a whole ‘nother essay here ruminating on this vaguely paradoxical proposition, as well as the theoretical question of the innately subjective nature of weirdness—if it becomes de rigeur, expected, familiar, is it still weird? Can we still call it weird when it satisfies the taxonomists?

Always a point of debate, but a critical mass of Lovecraft scholars cite the period between 1926 (when his marriage effective ends and he returns to Providence from his miserable sojourn in New York City) and 1934. In H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life, Michel Houellbecq offers a representative list of Lovecraft’s “great texts,” which uncoincidentally comprise what August Derleth would later designate the “Cthulhu Mythos”:

“The Call of Cthulhu” (1926)

“The Colour Out of Space” (1927)

“The Dunwich Horror” (1928)

“The Whisperer in Darkness” (1930)

At the Mountains of Madness (1931)

“The Dreams in the Witch House” (1932)

“The Shadow Over Innsmouth” (1932)

“The Shadow Out of Time” (1934)

Houellebecq identifies these stories as “the absolute heart of HPL’s myth” (51).

“Eldritch” is a favourite word of Lovecraft’s, and it has become more or less synonymous with his particular strain of the Weird. The OED defines it as “Weird, ghostly, unnatural, frightful, hideous,” and observes that its origins are obscure, but probably deriving from Scottish. It is possibly a derivative of “elf” in the sense of “Senses relating to otherworldly or magical beings,” deriving from the form elphrish.

The origin story of this interest was writing a conference paper on the film The Cabin in the Woods, which ended up being a Lovecraftian reading. I ended up developing the argument into an article, which was published in Horror Studies 6.1 (2015) as “‘We are not who we are’: Lovecraftian Conspiracy and Magical Humanism in The Cabin in the Woods.” As the title indicates, it was also an early essay in a line of thinking that has brought me to this Substack page.

Really tried to make a joke on the old mystery genre cliché of “the two cases were connected the whole time!” but unfortunately couldn’t stick the landing.

This is a hill I’m perfectly willing to die on. I have read a significant number of apologias for Lovecraft’s prose and for his (to be charitable) unconventional storytelling. I’m willing to grant that “the weird style” is a thing and that Lovecraft’s lugubrious and ornate writing does occasionally work to interesting effect, but taken overall … bad prose is bad prose. He might have had a style, but he was no stylist.

Miéville here quotes from S. T. Joshi’s book, A Dreamer and a Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time (2001).

This racial hierarchy is broadly consonant with the so-called “race science” prevalent in the early years of the twentieth century, most notably in such bestselling books as Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916) and Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color (1920)—books whose huge popularity was largely unaffected by the fact that their pseudoscientific premises were debunked in short order. Madison Grant was actually cited by Nazi defendants at the Nuremberg trials; Hitler himself had said of The Passing of the Great Race that “This book is my Bible” (Spiro xi). And again, whether or not Lovecraft had read these works of “scientific racism,” stories like “The Horror at Red Hook” exhibit the kind of granular gradations of racial superiority that form the basis of Grant’s system—in which white Europeans themselves fall into a biologically determined hierarchy, with “Nordics” at the apex, followed by “Alpines” and “Mediterraneans.”

Which isn’t much of a modification; hyperobjects as described by Morton tend to be at once massive and diffuse. However, the representative list he offers at the start of his book Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World includes so examples that are definitely not invisible or intangible, and I want to fudge his meaning:

A hyperobject could be a black hole. A hyperobject could be the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, or the Florida Everglades. A hyperobject could be the biosphere, or the Solar System. A hyperobject could be the sum total of all the nuclear materials on Earth; or just the plutonium, or the uranium. A hyperobject could be the very long-lasting product of direct human manufacture, such as Styrofoam or plastic bags, or the sum of all the whirring machinery of capitalism. Hyperobjects, then, are “hyper” in relation to some other entity, whether they are directly manufactured by humans or not. (1)