We’re back with a video, at long last! Hopefully we won’t go that long again. This will be the last Tolkien-themed video for a spell. We’ll circle back around to the The Professor sometime later, but what’s in the hopper right now is a video pondering the question of just why we’ve had so many multiverse-themed movies in the past several years. After that, I have a few ideas simmering—most likely will be one on Game of Thrones and the way it deals with the theme of fate and destiny.

But for now, here’s our video on Tolkien and the uncanny, and what the uncanny has to do with magic in Middle-earth. You can also find our YouTube page here to see all the videos we’ve done so far.

This one gets a bit academic, but I quite like it—it’s a distilled version of a lecture I give in my class on The Lord of the Rings. Stephanie (my beautiful and talented wife who edits and produces these videos)1 had a hell of a time figuring out how to find and create images for some of the more abstract bits, but because she’s brilliant it worked out beautifully.

As always, I provide here the unedited script. There’s about eight hundred words here that I cut for the video.

In our previous video, which looked at the way Tolkien’s magic often coalesces around different conceptions of “home,” I said that I wasn’t then going to do a deep dive into the nature of magic in Tolkien’s legendarium. That deep dive, I said, would wait for a future video. I amend that now to future videos, plural. Tolkien’s magic is at once inescapable but nebulous: it permeates his fictional world, but unlike the histories and languages of Middle-earth, it is never explicated in any specific detail. Hence, any consideration of Tolkien’s work necessarily considers its various magical elements, without necessarily talking about it as such.

Well … we’ve looked at his magic of home; and now let’s consider a related aspect, Tolkien’s uncanny.

When I say “Tolkien’s uncanny,” probably what leaps to mind are all the scary moments in LotR: the first encounters with the Black Riders, the attack on Weathertop, the darkness of Moria and the appearance of the Balrog, and of course Sam and Frodo’s encounter with Shelob (to name just a few). But “scary” and “uncanny,” while having some overlap, don’t mean the same thing. The uncanny is more eerie than terrifying, more unsettling than frightening.

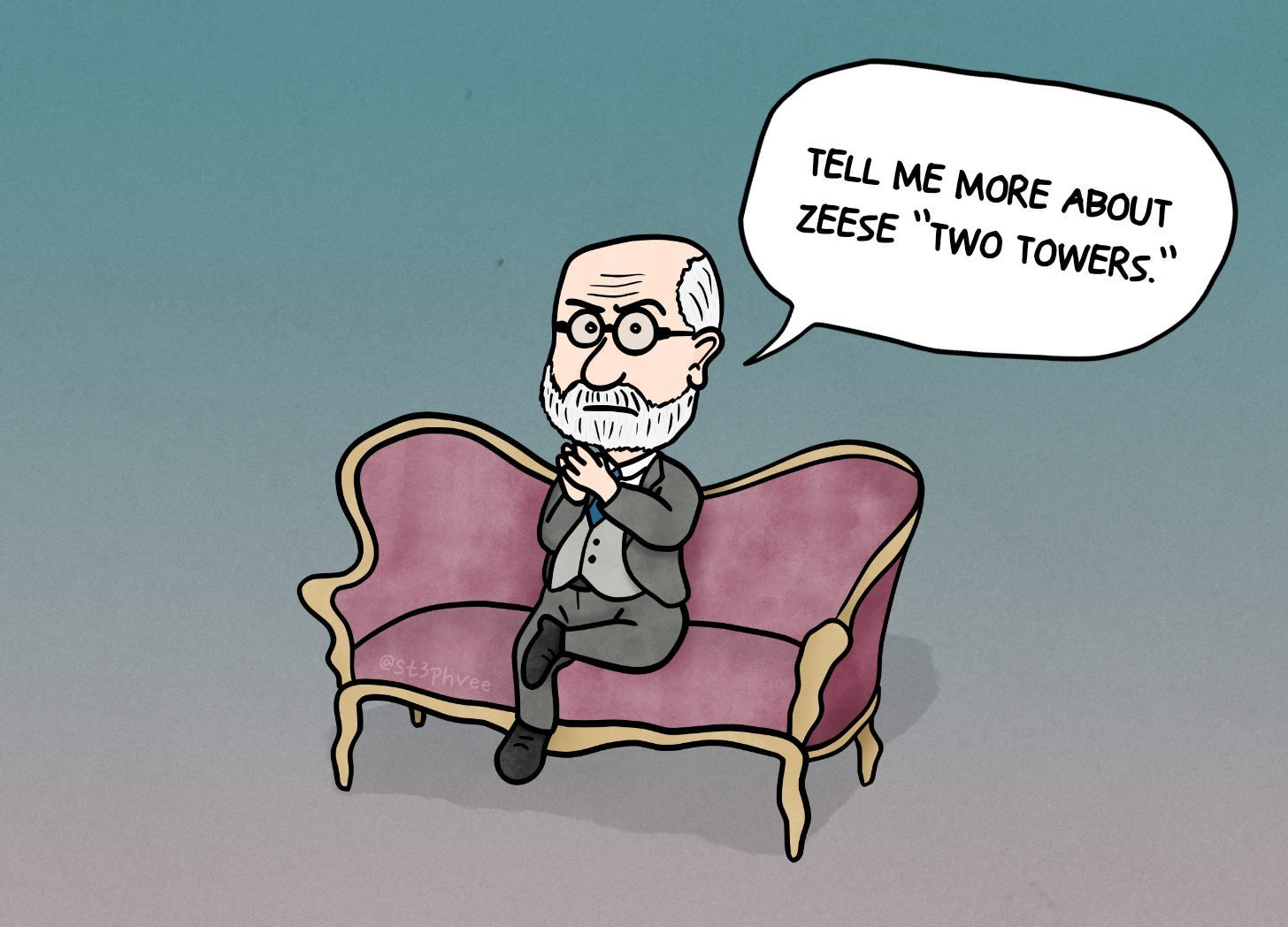

In this respect, the English word “uncanny” is actually less useful than the German. Unheimlich literally translates as “unhomely,” the opposite of heimlich—homely—which means “intimate, friendly, comfortable; the enjoyment of quiet content” and “arousing a sense of agreeable restfulness and security” (Freud 342). To experience the unheimlich, then, is to be not at home, to be possibly exposed, and unsettled.

The uncanny as “unhomely” is an understanding derived from Sigmund Freud. When I first read his essay “The Uncanny” in the course of my undergrad years, Freud’s explication of the term made something I’d never quite understood in Tolkien make sense.

During my first readings of LotR, I remember thinking it odd that Rivendell was known as “the Last Homely House.” “Homely” did not seem an appropriate word to me, as I understood it in today’s more common usage, namely plain, and unattractive … neither of which are descriptors that apply to the House of Elrond. Rivendell, indeed, is the antithesis of plain and unattractive. So, in my mind I tended to delete the L, but even “the Last Homey House” still didn’t quite cut it. Rivendell is more than merely homey. It was an odd little detail my mind bumped against, but not so much I dwelt on it overmuch. It was only many years later, when I read Freud’s essay, that Tolkien’s use of the word “homely” started to make perfect sense.

In our previous video, I suggested that magic in Middle-earth often manifests in place, with different locations assuming the relative power and nature of their inhabitants: malevolence and malignity blight the land (as with Mordor and Mirkwood), but benevolence and love imbue the land with its own magical protections—Rivendell, Lothlorien, the last lingering influence of the Elves in Hollin, and of course the Shire.

I want to expand on that discussion here, but with a focus on Tolkien’s uses of the uncanny. At first glance, that might seem an odd choice. Didn’t I just get done explaining how the uncanny is precisely the opposite of the comfort and security—and magic—of home? Well yes. And no. And that’s where it gets interesting.

Freud’s essay is useful to us in part because he argues that when we define “uncanny” as merely “eerie,” we’re missing half the meaning. Prior considerations of the term, he suggests, “[do] not get beyond this relation of the uncanny to the novel and unfamiliar,” but that “It is not difficult to see that this definition is incomplete” (341). At issue, Freud argues, is that there are two primary definitions of Heimlich, and therefore, because unheimlich is its negation, two equal and opposite meanings.

Heimlich is “of the house” or home, friendly, familiar, intimate, comfortable. Also: secure, domestic (and domesticated), and hospitable. But the second related meaning connotes secrecy: Heimlich means concealed, hidden, or private. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that “In several cognate Germanic languages, the parallel adjective shows a semantic development from ‘private’ to ‘secret, clandestine’ or ‘mysterious.’”

Thus unheimlich, as the negation, entails being “not of the house,” unfriendly, unfamiliar, discomforting, unsecure, inhospitable. But by the same token, it is also unconcealed, unsecret; that which is made known; that which is supposed to be kept secret but is revealed—perhaps inadvertently.

It’s the second half of these definitions that makes the uncanny a particularly fascinating—and particularly useful—term. We see in the simultaneous meanings of intimate and comfortable on one hand and concealed and secret on the other an obvious continuity—secrecy is consonant with privacy, and privacy is one of the qualities we associate with the home. But at the same time there potentially lurks sinister subtext, as the secrecy of the home can also conceal a host of abuses, of violent acts, of indiscretions and transgressions past and present. In gothic horror, after all, it is most often houses that are haunted—haunted by revenants of pain and trauma, and such stories usually entail the revelation of those old secrets.

But you might be asking: what does this have to do with Tolkien? Well, quite a lot, I want to suggest. We should note first that, though Tolkien on one hand had no particular use for Freud and his psychoanalytic theories, he would have been intimately familiar with the nuances of Heimlich and unheimlich—his first scholarly job was as an editor on the Oxford English Dictionary, and his area of expertise was with Nordic and Germanic languages. So calling Rivendell the Last Homely House wasn’t accidental—something we can further discern from the fact that in the first draft of The Hobbit, he has Gandalf call it the Last Decent House … which after a few pages he changes to Homely, making a marginal note to go back and change all the prior “Decents.”

We first encounter Rivendell in The Hobbit,2 and it is quite clear that it is a place of magic and enchantment. “Evil things did not come into that valley” (61), Tolkien tells us; in FotR we get a deeper understanding of Rivendell’s magic, when Gandalf makes clear to Frodo that it is one of the few places in Middle-earth with the power to resist the might of Mordor (albeit just “for a while” [290]). But where in FotR Frodo wakes up in Rivendell, Bilbo and the dwarves have a decidedly difficult time finding the place—even with Gandalf acting as their guide: “it was not so easy as it sounds to find the Last Homely House west of the Mountains” (55). The only path “was marked with white stones, some of which were small, and others were covered with moss or heather” (56). Though Gandalf ostensibly knows the way, it’s very slow going: “His head and beard wagged this way and that as he looked for the stones, and they followed his lead, but they seemed no nearer to the end of the search when the day began to fail.”

We might be inclined to shrug at this small discrepancy between The Hobbit and LotR—perhaps Rivendell is as difficult to find in the latter, but there’s no real indication of that. There are no complaints, for example, from Boromir about repeatedly getting lost on his way from Gondor to the Council of Elrond. But while the way to Rivendell isn’t hidden per se in LotR, there is nevertheless a powerful sense of the place’s secrecy. It is hidden, not from our heroes, but from the Eye of Sauron. The most significant exemplar of the hidden and secret in Rivendell is only revealed in the final pages of RotK, when we see Elrond openly wearing one of the three Elven-rings: “Elrond wore a mantle of grey and had a star upon his forehead, and a silver harp was in his hand, and upon his finger was a ring of gold with a great blue stone, Vilya, mightiest of the Three” (1344-45). In this moment we also see that Galadriel wears Nenya, the ring of mithril … which Frodo (and by extension us the readers) already know (more on this in a moment), and then we learn Gandalf wears the third, Narya.

Without getting too much into the history of the Rings of Power, it’s worth noting how much of it is about secrecy, hiding, and revelation. The precipitating action of LotR is Gandalf’s suspicion, and then realization that this little magic ring Bilbo accidentally stole from Gollum is actually the One Ring to Rule Them All. Even before he confirms this fact, he enjoins Frodo to “Keep it safe, and keep it secret!” (53). In The Hobbit, the Ring itself functions as a means of hiding oneself: Bilbo, brought on to the dwarves’ Quest in the unlikely capacity of burglar, proves surprisingly adept in that role, not least because he can make himself invisible with the Ring.

Like much in The Hobbit that carries over into LotR, the Ring’s power of invisibility becomes somewhat more … complicated. Bilbo’s use of the Ring is quite simple and straightforward, and indeed during the dwarves’ captivity in the halls of the Elven-king Bilbo remains invisible for days at a time with no ill effects. But the wearing of the Ring in LotR is rather more problematic: though the wearer becomes invisible to other corporeal mortals, they become visible to the spirit-realm. In the fateful moment on Weathertop when Frodo puts on the ring, the advancing Nazgûl become suddenly, startlingly clear:

Immediately, though everything else remained as before, dim and dark, the shapes became terribly clear. He was able to see beneath their black wrappings. There were five tall figures … In their white faces burned keen and merciless eyes; under their mantles were long grey robes; upon their grey hairs were helms of silver; in their haggard hands were swords of steel. (255)

What was visible (Frodo) becomes invisible; what was invisible (Ringwraiths) becomes visible. What’s more, Frodo becomes visible to them; as Gandalf gravely notes when Frodo wakes up in Rivendell, “You were at your gravest peril when you wore the Ring, for you were halfway in the wraith-world yourself, and they might have seized you. You could see them, and they could see you” (289).

The Nazgûl stab Frodo with a knife whose tip breaks off and burrows deeper; if the shard reaches his heart he will himself become a wraith. As they approach Rivendell, the corporeal world fades around him while other things become visible. When he crosses the river and looks back, he can now see the Nazgûl as he did when he wore the Ring: “they appeared to have cast aside their hoods and black cloaks, and they were robed in white and grey. Swords were naked in their pale hands; helms were on their heads” (279).

With his last failing senses Frodo heard cries, and it seemed to him that he saw, beyond the Riders that hesitated on the shore, a shining figure of white light; and behind it ran small shadowy forms waving flames, that flared red in the grey mist that was falling over the world. (280)

Later, when he asks Gandalf if the shining figure was the Elf Glorfindel, Gandalf replies, “Yes, you saw him as he is upon the other side: one of the mighty of the Firstborn” (290).

This invisible/visible, hidden/revealed opposition pervades LotR: what we come to understand is that magic in Tolkien exists as a function of this uncanny dialectic. Tolkien’s elves, especially those “High Elves” more closely related to the godlike Valar, are themselves uncanny … both in the magical sense and the ways they excite both wonder and suspicion among mortals in equal measure. An early encounter in FotR establishes this dynamic. We already know that Sam is fascinated with elves and wants nothing more than to meet them. He has his wish granted even before the hobbits leave the Shire. The have a close call with one of the Nazgûl, which almost finds them hiding when it is scared off by a band of elves traveling through the Shire. This moment of deus ex machina3 saves the hobbits and gives us our first glance of the Fair Folk in LotR. They bring the hobbits along with them and share their music and feast when they pause for the night. The hobbits wake the next morning much as many mortals do in the aftermath of a Faerie encounter, except that their memories are clear.

Frodo asks Sam what he thought of his first meeting with elves. “They seem a bit above my likes and dislikes, so to speak,” Sam replies. “It don’t seem to matter what I think about them. They are quite different from what I expected—so old and young, so gay and sad” (113-114). As usual, Samwise Gamgee is at once our proxy as readers in experiencing the magic of Middle-earth, and the voice of wisdom, cloaking key truths of the story in his roughspun language. But he gets at a key dimension of elves, who are simultaneously old and young, joyful and mournful, and profoundly other than mortals. That their arrival is in contrast with the dread of the Nazgûl is significant, dramatizing two extremes of the uncanny … and though Sam is the open-minded type who sees the beauty and wonder of elves, there are more than a few times when mortals exhibit the fear and distrust that are the flip side of Sam’s delight.

We encounter this dislocation most strikingly in Lothlorien. Though Elrond opens The Last Homely House to Free Folk of good hearts, the elves of Lothlorien have long been more insular and guarded, which has in turn made the neighbouring mortals in Rohan and Gondor fearful. As the Fellowship approaches Lothlorien, Boromir expresses reluctance. “Is there no other way?” he demands. To which Aragorn responds, “What other fairer way would you desire?”

“A plain road, though it led through a hedge of swords,” said Boromir. “By strange paths has this company been led, and so far to evil fortune. Against my will we passed under the shades of Moria, to our loss. And now we must enter the Golden Wood, you say. But of that perilous land we have heard in Gondor, and it is said that few come out who once go in; and of that few none have escaped unscathed.” (440)

Aragorn corrects Boromir on the details but not the spirit of his concern, saying unscathed is the wrong word to use: “but if you say unchanged, then maybe you will speak the truth.” And when Boromir reluctantly agrees to proceed but warns that Lothlorien is “perilous,” Aragorn agrees with another modification: “fair and perilous,” he amends, which is a reasonable approximation of the meaning of sublime—not merely beautiful but awe-inspiring to the point of fear. Transfiguring in its spiritual aspect.

The Fellowship’s respite in Lothlorien, while recuperative, is also uncanny and transformative. None depart unchanged, both positively and negatively: at one end, Gimli and Legolas forge a bromance for the ages; at the other, Boromir’s nascent desire for the Ring burrows deeper in his heart. And Frodo and Sam have an encounter with elf-magic, which itself proves to be about revelation and making the invisible visible.

Their glimpse into the Mirror of Galadriel is anticipated by Galadriel’s test of the Fellowship: “[S]he held them with her eyes and in silence looked searchingly at each of them in turn. None save Legolas and Aragorn could long endure her glance. Sam quickly blushed and hung his head” (464). Later, they all share that “each had felt that he was offered a choice between a shadow full of fear that lay ahead, and something that he greatly desired” (465), if just they would abandon the Quest.

We find in Galadriel’s test the epitome of the uncanny in the fraught tension between secrecy and revelation. Never mind the deeply disconcerting experience of having a beautiful and terrifying elven queen read your thoughts; Galadriel’s test is about revealing your own secrets to yourself, making your own mind unhomely. She later offers Frodo and Sam more possible revelations when she invites them to look into her mirror, a shallow basin of water.4 “What shall we see?” Frodo asks.

“Many things I can command the Mirror to reveal,” she answered, “and so some I can show what they desire to see. But the Mirror will also show things unbidden, and those are often stranger and more profitable than things which we wish to behold. What you will see, if you leave the Mirror free to work, I cannot tell. For it shows things that were, and things that are, and things that yet may be.” (470-471)

Turning to Sam, she notes that “this is what your folk would call magic … Did you not say that you wished to see Elf-magic?”

Looking in the mirror, Sam and Frodo see a jumble of bewildering scenes, many of which only become comprehensible in hindsight. And then Frodo sees the Eye of Sauron, “searching this way and that, and Frodo knew with certainty and horror that among the many things that it sought he himself was one. But he also knew that it could not see him—not yet, no unless he willed it” (474). When, “shaking all over,” Frodo steps away from the Mirror, he sees on Galadriel “a ring about her finger,” which “glittered like polished gold overlaid with a silver light, and a white stone in it twinkled as if the Evenstar had come down to rest upon her hand” (475).

In this moment, Frodo sees that Galadriel wears one of the three Elven-rings. “[It] is not permitted to speak of it,” she tells Frodo, “But it cannot be hidden from the Ring-bearer, and one who has seen the Eye.”

The Eye of Sauron is uncanny in the most basic sense of the word—“rimmed with fire … glazed, yellow as a cat’s,” with the “black slit of its pupil open[ing] on a pit, a window into nothing (274)—but is itself, quite obviously, a metaphor for the seen and unseen. The entire Quest indeed hinges on Frodo and the Fellowship hewing to Gandalf’s directive to “Keep it safe, and keep it secret!” (53) … to keep it, in other words, heimlich, homely. There is something of an irony that the moment of revelation at the end, when Frodo puts on the Ring while in Mount Doom, is a profoundly unheimlich moment for the Dark Lord: it is both the disconcerting unveiling of a secret, and it prefaces Sauron’s imminent unhousing.

REFERENCES

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny.” The Penguin Freud Library. Ed. James Strachey. Vol. 14. Penguin, 1985. 335-76.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Book of Lost Tales Part One. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, 2002.

----. The Hobbit. Harpercollins, 2007.

----. The Fellowship of the Ring. HarperCollins, 2007.

----. The Two Towers. HarperCollins, 2007.

----. The Return of the King. HarperCollins, 2007.

NOTES

Steph recently started her own Substack called Discon/Net, which is all about the sorry state of current internet culture and her various attempts and strategies to wean herself off her screens. It’s quite awesome, you should check it out.

One of the earliest versions of Rivendell in Tolkien’s legendarium is “The Cottage of Lost Play,” which appears in The Book of Lost Tales Part One. It describes a house in which travellers may pause in their journey and rest and refresh themselves with story and song: “Eriol stepped in, and behold, it seemed a house of great spaciousness and very great delight, and the lord of it, Lindo, and his wife, Vairë, came forth to greet him; and his heart was more glad within him than it had yet been in all his wanderings” (14-15). The cottage is called Mar Vanwa Tyaliéva, the "House of Past Mirth" in Quenya, which Tolkien retains as one of the names of Rivendell.

Hearing their song, Frodo exclaims in astonishment, “These are High Elves! They spoke the name of Elbereth!” (104). Given these elves’ closeness to the Valar, their machina is more literally deus than one normally encounters with that expression.

Always this makes me think of the opening lines of George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859): “With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader.”