I often think about things in terms of Venn diagrams. The more I think about 28 Years Later, the more I see in my mind’s eye a bunch of overlapping circles labelled “zombie apocalypse,” “eco-horror,” and “the New Weird.” (There’s probably a few others I’m not thinking of yet, but we’ll start with these three.) This film has excited my thinking in part because that overlap is a sweet spot where a bunch of my thinking and teaching from the past several years intersects.

A significant number of the classes I’ve recently taught at the fourth-year and graduate level have pinballed back and forth between Weird fiction (as I have discussed over a series of posts here) and post-apocalyptic narratives.1 There have always been a few points of contact between those subjects, mostly in terms of apocalyptic visions that engage with environmental fables: not so much overt visions of climate change-induced catastrophe as stories that feature a sort of ecological revenge.2

This is an important distinction that will become relevant to my deeper dive into 28 Years Later—the difference between the conventional secular apocalypse, and one that occurs through the natural emergence of something that either eliminates humanity or transforms us. In the first version, the end comes by way of our own actions or those of an outside force—nuclear war, climate catastrophe, contagion, alien invasion, asteroid, etc. In the second, something within our own environment revolts, and either supplants humanity or changes it beyond recognition. There is, to again think like a Venn diagram, a lot of potential overlap there; ecological revolt can be spurred or otherwise inadvertently engineered by technological misadventure. Viral contagion falls into this overlap, or any Cold War era nightmare about radiation-mutated flora or fauna.

A subgenre within the subgenre of climate catastrophe fiction (cli-fi) imagines such scenarios. Per one example, M.R. Carey’s Ramparts trilogy—The Book of Koli (2020), The Trials of Koli (2020), and The Fall of Koli (2021)—depicts a future Britain in which humanity has been reduced to neo-medieval precarity within a handful of walled enclaves because, some indeterminate number of centuries earlier, humans’ various attempts to manipulate nature resulted in an unremittingly hostile natural world. Every plant and animal, it seems, has evolved to kill humans, who now live behind palisades and defend themselves (ironically) with a small few pieces of advanced weaponry left over from pre-apocalyptic times.

(I cite the example of M.R. Carey’s trilogy both because it exemplifies this one sub-sub-genre, but also because I’ll be coming back around to discuss his Hungry Plague zombie duology, The Girl With All the Gifts (2014) and The Boy on the Bridge (2017) in this final part of this essay.3)

I’ve written this in three parts: a discussion of your bog-standard zombie apocalypse of the post-George A. Romero variety; diving into 28 Years Later and its preceding films; and finally teasing out some of the potential implications of the changes in Years by way of comparison to other “evolved” zombie properties and a judicious measure of rank speculation.

1. Zombies, Stasis, and Mass Culture

Zombies have developed their cultural cachet to a large degree because they are allegorically malleable. That is to say, it’s easy to project onto them whatever fears and anxieties are culturally front of mind at any given time.

This observation has been made so frequently that it has the quality now of boilerplate. Like the caveat that, yes, the infected of the 28 Days films aren’t technically zombies, it’s the sort of acknowledgment one feels obliged to make when dipping into this long-running discussion. And it’s true enough, for what it’s worth: it’s no strenuous task to argue that the walking dead have variously represented enslavement, communism, fascism, conformism, groupthink, consumerism, mobs and mob violence, mass culture, infection and disease, or even terrorism.4

At the same time, it’s not true that zombies can represent anything. They have a very broad but not infinite metaphorical remit. For the larger swath of zombie properties across media, one of their key features is stasis—which is to say, they are unchanging except for the tendency to rot away (so, stasis with a side helping of entropy).5 Depending on a given story’s zombie mythology, the undead may wander indefinitely if not put down, or become increasingly dessicated until falling apart. 28 Days Later and then 28 Weeks Later take as a central premise—though I suppose in hindsight assumption would be the more appropriate word—that the infected will eventually die off from starvation.6

This stasis is thematically significant, indeed crucial, as it stands in contrast to the small bands of survivors around whom these stories revolve, who have to adapt and develop in response to the challenges of their new reality. Zombies’ stasis also functions as a counterpoint to the more general wish fulfilment underpinning post-apocalyptic narratives, which is about progressing beyond the old world.7 The fantasy of starting over—both as an individual and as a society—is foundational to zombie apocalypse, as it entails the burning down of a sclerotic civilization and emerging in the ruins with renewed purpose and a more authentic existence (however harrowing an traumatizing that existence may be at times). In this respect it is about renewal, whereas the undead hordes comprise the revenant of the pre-apocalyptic world, now helpfully shorn of its bells and whistles and transparently dead-eyed and soulless as it threatens to absorb you back into the vacuity of mindless consumption.

This particular reading gives substance to purists’ insistence that 28 Days Later’s infected are definitionally not zombies—not just because they’d not undead, but because the metaphor of the living dead is thematically crucial to seeing zombies as a cultural revenant of a dead civilization. That being said, the traditional zombie apocalypse mechanics are still very much at work in Days: the infected are undifferentiated and static (albeit bloody fast) and representative of pre-apocalyptic mass culture. For Days, perhaps more than any property that followed in the still-ongoing zombie apocalypse boom, the pre-apocalyptic was the post-9/11.8 The infected embody the rage and fear of the period following the shocking spectacle of the Twin Towers’ destruction. As Nicole Birch-Bayley asserts, the primary anxiety articulated by Days and the glut of similar films following its example deals with:

societies and populations that proved ill equipped to cope with the overwhelming spread of violence and disease; the human crisis became directly linked to authentic global concerns, such as wars on terrorism, political revolutions, inadequate governments, weapons of mass destruction, viral epidemics or even pandemics, which continue to be referenced in the contemporary media. (1138)

At the same time, I don’t want to wave away the distinction between “infected” and “living dead,” as it does signal a paradigm shift that has become more pronounced in the past ten years.

2. The Infected and Their Discontents

So, let’s get into 28 Years Later, starting with a quick recapitulation of a few significant elements of Days and Weeks. As mentioned above, a key assumption advanced in both those films was that the infected would die off from starvation. The Rage Virus, it is implied, destroys all brain functions besides the drive toward violence, obviating even hunger and the need to eat. Hence, twenty-eight weeks (or so) after the events of Days, NATO forces feel confident about beginning to repopulate the U.K. starting with London.9

Spoiler: it goes badly … because though it does seem that the infected have died off, a carrier of the virus remains. In the opening sequence a house sheltering a group of survivors, including Don and Alice Harris (Robert Carlyle and Catherine McCormack), is overrun. Don is separated from Alice; rather than try to go back for her, in an instant of what is both cowardice and a recognition of the futility of trying to save her, he runs. But as it turns out, she is immune. She is found by her children, who have rejoined their father (they were fortuitously away in the U.S. at the time of the outbreak). Determined to retrieve some keepsakes from their old him, they evade security and venture out into London. There at their family house they find Alice: traumatized, malnourished, and practically feral, but not showing viral symptoms.

Wracked with guilt, Don uses his security key to get into her holding room where she’s strapped to a gurney for observation. He kisses her … and that’s all she wrote. He becomes infected and, after beating the helpless Alice to death, runs madly through the enclosed compound and starts a viral cascade.

What’s notable is that Don exhibits slightly different traits from the usual Rage host. For one, he is more focused and his rage more brutally directed at the people he loves. His brutal beating of Alice is the first case in point; then, he doggedly pursues his children, even when they disappear into the London Underground. The fact that he so fixates on his family suggests a vestigial memory at work, the inverse of his love finding expression in violence and rage. What this suggests is that he has a new strain of the virus—one likely mutated by its time spent incubating in his immune wife.

Fast forward three decades, and the infected have changed rather dramatically. For one thing, they have learned to eat: a few intercut clips show a group of them at night, eyes glowing, as they tear apart a deer carcass. They have also developed subspecies, the first of whom we meet are the slow-lows—a mostly harmless but revolting and corpulent strain that has adapted to eating worms and grubs as they crawl along the ground. The other, far more terrifying variant are the Alphas: massively tall and bearded, looking like something between a Viking berserker and WWE heel. Some brief exposition is offered by the Swedish soldier Erik, about how the virus reacts to a certain steroid in some cases, resulting in red-eyed man mountains. They possess a rudimentary intelligence, acting in a sort of leadership role over bands of regular infected. In the Britain of 28 Years Later, the infected would seem—when under the influence of an Alpha—to have formed simplistic primate societies akin to chimpanzees.

And like alpha chimps, the Alphas assume droit de seigneur with their females. The sequence in which Isla comes across a female infected in the midst of childbirth and helps her through the ordeal is profoundly suggestive of changes introduced to the 28 Days lore. For one thing, the infected woman is non-aggressive while in labour; Isla holds her hands as the baby is born. After the child has been birthed and the cord cut, she suddenly reverts to Rage-inflected hostility, leaving us to speculate about the power of birth hormones.

Then there is the fact that the infant is non-infected—or at least appears to show no symptoms. The doctor Kelson marvels about the wonders of the placenta, but even if it’s posited that the Rage Virus cannot penetrate the placental barrier, one would assume the process of childbirth itself would open the infant up to a pathogen that—as has been amply demonstrated—is extremely easily transmitted.

Unless, of course, the infants of infected are born with the same immunity as carried by Alice Harris.10 Which doesn’t explain how a child born to an infected has any chance of survival, but it does raise other questions—not least of which is about the latent humanity of the infected three decades after the events of the first film. If the people of Holy Island and other survivor enclaves around the British Isles have regressed to a neo-medieval existence, the infected would seem to be progressing to something vaguely neolithic. And while primitive, it still represents a fundamental break away from the stasis of the classic zombie apocalypse: hypothetically, left to their own devices for millennia, the infected might recapitulate something like human evolution. Or, more likely, evolve into something entirely different and new …

I’m starting to get into How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth territory—also known as rank speculation—so I’ll try to curtail my descent into unsubstantiated conjecture. It’s entirely possible that the next two planned Years films will answer some of these questions. For the moment, I’ll turn my attention to the ways in which the infecteds’ changes are consonant with other zombie evolutions.

3. Mycelial Zombies and the Utopian Weird

Way back when I was teaching my American Weird course this past winter, I posted a series of essays in which I unpacked my three very rough categories of the Weird—banal, relative, utopian. After doing a very deep dive into the relative Weird (and a much shallower dive into the banal Weird), I’d promised to eventually get to an essay discussing the utopian Weird.

This ain’t it. But it does get into some similar subject matter.

One caveat is that my use of the word “utopian” in this context is perhaps counter-intuitive. What’s being imagined isn’t Utopia per se but rather strains of utopian thought and possibility, in which one predicate is allowing for the possibility that there are futures other than the human, or that the “human” as a category isn’t necessarily impermeable but is open to adaptation, change, and evolution.11 There is also the fact that what I’m discussing here isn’t the utopian Weird, but rather stuff that shares its DNA.12

The introduction of variation into the zombie horde, in which there are different classes or species, is a significant change when you consider the conceit of stasis as I discuss above; alongside stasis is the fact of the horde being undifferentiated, meaning that the classic Romero-style zombie is resolutely non-individuated.13 The critical mass of zombie properties since 28 Days Later hews to this convention.

The major exception to this convention has always been video games, whose zombie apocalypse and zombies-as-enemies properties similarly exploded in the past two decades.14 That video games would want a selection of undead makes a certain amount of sense, as that translates into more interesting and challenging gameplay—a hierarchy of difficulty, with the rarer varietals offering periodic boss battles. Anybody who played Left 4 Dead—a game a friend of mine described as “you’re in 28 Days Later, but with guns!”—will recall with a shudder the Hunter, Smoker, Boomer, and Tank, but also probably still carries residual trauma from the distant wail heralding the arrival of the Witch. Resident Evil and The Last of Us similarly feature zombie classes differing speed, strength, endurance, and intelligence.

And while the most prominent examples of zombie variety in film and television have in fact been adaptations from video games, it has become more commonplace. The Last of Us (2013) is perhaps our best example, in part because the “classes” of zombies reflect different stages of the effects of the infection as it takes over its host, making it stronger and harder to kill as it goes. The Last of Us—both the games and the HBO adaptation—reflect the movement of zombie apocalypse away from viral infection and the adoption of the fungal zombie. The cordyceps fungus—one strain of it, anyway, ophiocordyceps unilateralis—is also called the “zombie-ant fungus” because it infiltrates ants’ bodies and takes over their central nervous system. The nightmare, of course, is in imagining a mutated form that could do that with the human brain. Which is precisely what The Last of Us in fact imagines.

The mycelial zombie is an interesting shift for a variety of reasons, not least of which being the new dimension of connectedness introduced by the shift from virus to fungus. The infected of The Last of Us are potentially connected by underground mycelial networks: in various scenes we see characters stepping on innocuous plant life that alerts a zombie horde possibly miles away to humans’ presence. In the second episode of season two, the idyllic walled community of Jackson comes under overwhelming attack when a clay pipe is cracked open and proves full of fungal threads. The infected themselves when not active settle into a vegetative state; the final stage of infection entails the person being absorbed entirely into the mycelial network.

This shift breaks the traditional zombie stasis—the mycelial zombie isn’t revenant but part of a new ecological order. This is even more pronounced in M.R. Carey’s novel The Girl With All the Gifts and its quite excellent film adaptation (2017). It depicts a post-apocalyptic Britain that has been overrun by a fungal infection of the cordyceps variety what turns all afflicted humans into “hungries” who are driven to consume raw flesh. The wrinkle Carey introduces into his iteration of the genre is that pregnant women infected with the fungus give birth to children who retain their human faculties while still susceptible to the ravenous hunger that drives them into bloodlust.15 Hence, we begin the story in a military base given over to the study of these children. Melanie (Sennia Nanua), the titular girl with all the gifts, and her fellow infected children, spend their days in something like a classroom being educated on the usual range of grade school subjects by their teacher Ms. Justineau (Gemma Arterton). They are all however secured in chairs with clear plastic masks over their mouths, for though they comport themselves like ordinary children, they can turn feral.

They are present in the hopes that studying them might yield a cure or a vaccine to protect against the cordyceps. But as the story proceeds, it is revealed that “study” also means killing and dissecting them; it becomes obvious at a certain point that Melanie possesses far greater humanity that many of the non-infected humans around her, especially the lead researcher Dr. Caldwell (Glenn Close).

I’ll leave a more substantive discussion of The Girl With All the Gifts for a future essay in which I’ll hopefully talk about M.R. Carey’s fiction more broadly. Significant for the moment is the fact that, though in many respects an entirely recognizable and in some ways even typical zombie apocalypse narrative, Gifts and its companion novel The Boy on the Bridge completely change the game. Without spoiling too much, the “zombies” aren’t leftovers of the old world but are—in Melanie’s words—“the next people.” Apocalypse in this instance isn’t the end of things, or the erasure of the old world for the benefit of select survivors, but a new stage of evolution.

Which is why the “uninfected” infant of 28 Years Later—which I put in scare quotes because … well, we’ll see!—really rang my bell when I watched it. It will be interesting to see where the next two 28 Years films go, and how much (if any) consonance Boyle and Garland bring to bear with Carey’s novels.

REFERENCES

Birch-Bayley, Nicole. “Terror in Horror Genres: The Global Media and the Millennial Zombie.” The Journal of Popular Culture 45.6 (2012): 1138-1151.

Kushner, Tony. Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. Playwrights Canada Press, 2011.

NOTES

Also in that mix has been fantasy and postmodernist fiction, but those are less relevant to this discussion. Not not relevant, for a variety of reasons, but I’m working on my brevity. Largely failing, but working on it nonetheless.

Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach series, which begins with Annihilation (2014), is an exemplar. It features a region somewhere in the American southeast—“Area X”—that has been overtaken by some sort of phenomenon that affects and transforms the genetic makeup of plant and animal life. Though it is never clear whether Area X is the result of human activity, alien invasion, or natural irruption, the threat posed to humanity isn’t simple eradication but transformation.

It is probably worth noting that the 2018 film adaptation of Annihilation was written and directed by Alex Garland, who wrote both 28 Days Later and 28 Years Later. While I’ll stop short of speculating on how much that project influenced 28 Years, I will note that the sensibilities of both films aren’t entirely dissimilar.

I am very keen to write something specifically about M.R. Carey’s apocalyptic visions; besides the Ramparts trilogy and the Hungry Plague duology, his most recent novels Infinity Gate (2023) and Echo of Worlds (2024) (together comprising the Pandominion duology) are quite extraordinary. Though in some ways they depart the post-catastrophe substance of the prior works, dealing with the discovery of travel between multiversal realities, they nevertheless reflect back on the very climate allegories animating his earlier works.

I add this last interpretation because a former grad school acquaintance of mine argued vehemently that the “fast” zombies of 28 Days Later and the 2004 Dawn of the Dead were a post-9/11 innovation that an individual, innocuous shambler would see you and BAM. I’m unconvinced by this but include it here because, hey, it was an argument that was made. And as I’ll go on to mention, the massive popularity of zombie properties across media was, at least chronologically, a definitively post-9/11 phenomenon.

To be clear: I’m talking specifically about the post-George Romero zombie, of which the infected of 28 Days Later are a refinement. The “classic” zombie is the product of dark magic, usually voodoo, in which a sorcerer or witch doctor resurrects a dead person to function as their slave. The first zombie film was 1932’s White Zombie; zombies appear periodically in horror films for the next three to four decades, always as the magically-directed automaton. George A. Romero changes the paradigm in 1968 with Night of the Living Dead, in which zombies are walking dead reanimated through some mechanism vaguely gestured at (in NOTLD, it’s hinted at being radiation from a fallen satellite, but that is never confirmed one way or another). The Romero zombie is a mass phenomenon: where the classic zombie is terrifying because it is relentless and single-minded in carrying out its master’s will, the Romero zombie’s threat lies in its numbers.

Such indeed is the hypothesis of Major Henry West (Christopher Eccleston), the psychotic army officer who takes in Jim, Selena, and Hannah; he has chained one of his men who was infected in a courtyard, to see how long it takes him to starve to death. This premise looks as if it is borne out in the final moments of the film, as we see a pair of emaciated infected, weakened to immobility, lying on a road. 28 Weeks Later picks up on this premise, er, assumption, with NATO forces beginning the process of “restarting” Britain with a fortified compound of recolonizers on London’s Isle of Dogs.

On the matter of zombie apocalypse, I refer you back to my main post and my quotation from John Hodgman.

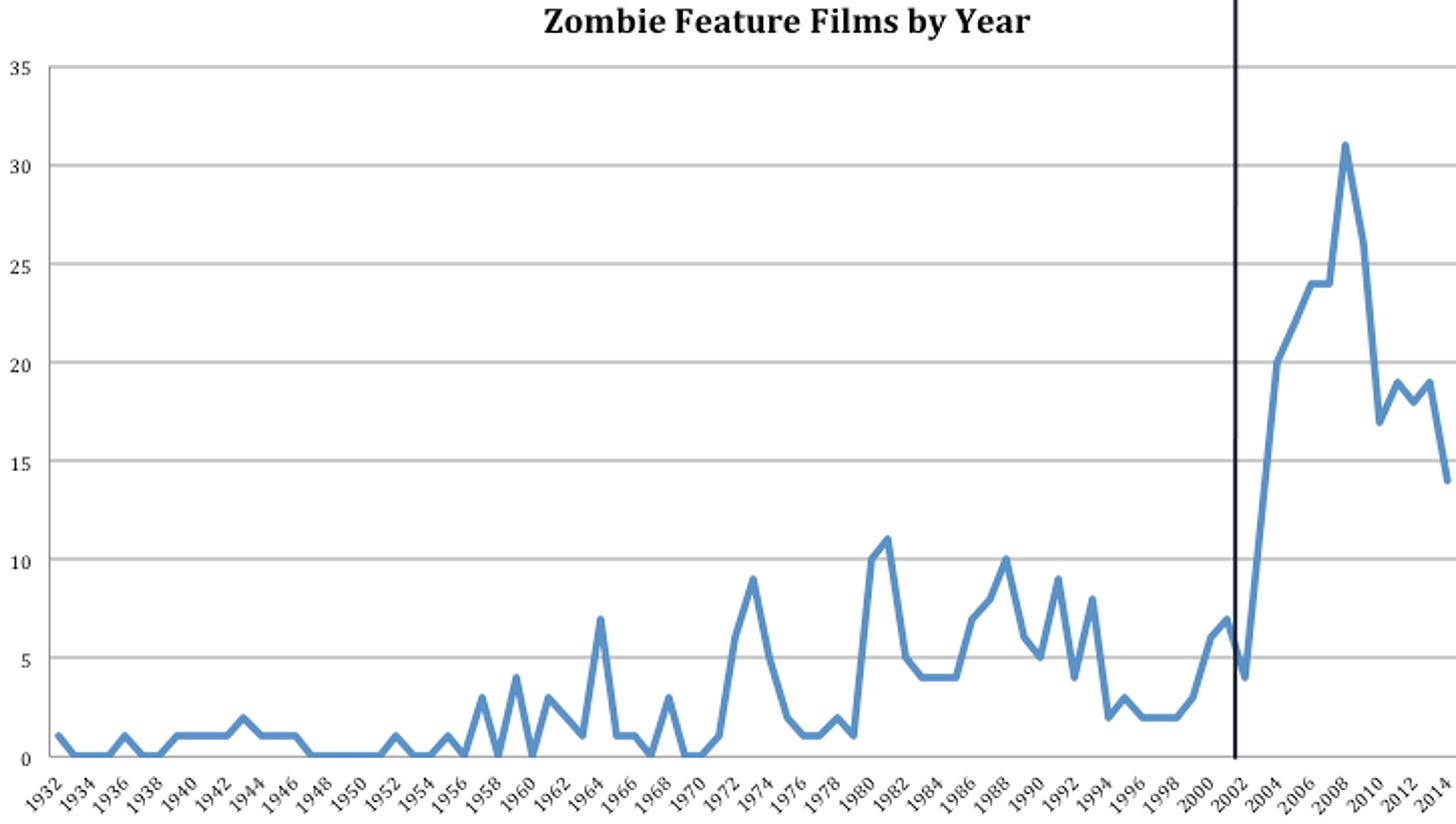

Though I am chary of confusing correlation with causation, there is no escaping the fact that the zombie apocalypse boom was at least chronologically a post-9/11 phenomenon. Ever since White Zombie (1932), zombies have been a consistent filmic presence, but never in large numbers. Even after Night of the Living Dead, there were only a handful of zombie films (often directed by George A. Romero himself) scattered across the three decades between 1968 and 2001. But then their numbers rise precipitously, peaking in 2009-2010 or so, but never returning to pre-9/11 numbers.

And that’s just in terms of feature-length cinema. It doesn’t consider television, fiction, and (perhaps most significantly) video games.

I don’t want to belabour what I see as a big plot hole, as from a thematic perspective it’s mostly beside the point. So, I’ll leave it out of the main text of this essay. But it will bug me if I don’t at least deal with it in a footnote, so …

As I deal with in the main text, Years posits an evolution of the infected—either a mutation of the virus and how it interacts with different hosts, or in adaptive behaviour of the infected, or both. That’s all good: but what seems to have happened is Alice that is the sole carrier of the virus, and when her husband Don kisses her and gets infected, he then starts the outbreak all over again. Presumably, the virus’s incubation in Alice has caused it to evolve, and indeed Don shows more focus and seems to retain vestigial memory as he hunts his children. So the seeds of the infecteds’ evolution in Years are planted here. So far so good.

But … if the massive hordes of infected from Days—a significant portion of the U.K.’s population, one assumes—have all died off, all we have at the end of Weeks is the relatively small number of infected from the Isle of Dogs compound, many of whom are killed when the military firebombed the place. But then three decades later the infected are numerous enough that far to the north of London the mainland is dangerous. We see of course that the infected now breed … but how do they survive out of infancy? It seems a bit of a stretch.

Which when you think about it is a dire possibility for the people of Holy Island, as Spike leaves baby Isla with them—a time bomb dropped in their midst that will go off the moment her blood or other bodily fluids are absorbed into a cut or scratch on a well-meaning wet nurse.

This is territory more thoroughly explored by one of our graduate students. Megan Boothby is a PhD student just coming into her comprehensive exams, who did a creative thesis MA exploring post- and transhumanist identities in a postapocalyptic Newfoundland. The novel that emerged from this project—working title Entanglements—is scheduled to be published by Penguin Canada in 2027. I always have Megan come into my Weird fiction classes to wax poetic about fungal futurities and cephalopod intelligence. When I dip my toe into these topics I feel like a dilettante by comparison.

The germ of an essay I started sketching back in March proceeded from one of those moments of serendipity that often happen to me when teaching—when a text or a lecture tangent in one class ends up resonating powerfully with the current subject matter in another. This often happens when the classes are dramatically dissimilar (in Fall 2023 I taught American Poetry and Critical Approaches to Popular Culture; you wouldn’t think these serendipitous moments would happen with two such classes, but they happened all the time). Late this past semester I was teaching Angels in America in my second-year course “U.S. Literature After 1945,” while in my fourth year “American Weird” we were doing The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin. The latter is a Lovecraftian novel set in New York City that is about the city coming to life as its own entity; really, it’s a specific inversion of Lovecraft’s racism generally and his antipathy to NYC generally, as it celebrates the diversity and fluidity of the city’s denizens.

The classes were back-to-back, with U.S. Lit after 1945 first. One day I focused on the scene in which Belize—Black, queer, nurse, former drag queen—describes the afterlife to Roy Cohn, the closeted legal monster who had been Joseph McCarthy’s right-hand man and later mentor to a young Donald J. Trump. He is in the final stages in his fight with AIDS. He asks Belize to describe the afterlife. Belize obliges him with what is possibly one of my favourite speeches in theatre:

Big city. Overgrown with weeds, but flowering weeds. On every corner a wrecking crew and something new and crooked going up catty corner to that. Windows missing in every edifice like broken teeth, fierce gusts of gritty wind, and a gray high sky full of ravens … Piles of trash, but lapidary like rubies and obsidian, and diamond-colored cowspit streamers in the wind. And voting booths … And everyone in Balencia gowns with red corsages, and big dance palaces full of music and lights and racial impurity and gender confusion. And all the deities are creole, mulatto, brown as the mouths of rivers. Race, taste and history finally overcome. And you ain't there. (209-210)

Roy, unimpressed, asks him what Heaven looks like. “That was Heaven, Roy.”

Though it sounds much better as spoken by the incomparable Jeffrey Wright, opposite Al Pacino as Roy Cohn in the HBO miniseries (2003):

Anyway. I’ll write that essay eventually. But this hopefully gives you a sense of my starting point.

Zombie aficionados will of course point out that Romero introduces zombie individuation in Day of the Dead (1985) with “Bub,” a zombie on whom medical experiments seem to effect a docility and revive memories of his former self; and in Land of the Dead (2005), some zombies start showing rudimentary intelligence, especially “Big Daddy,” who comes to function as a de facto leader of the undead in their climactic assault on the survivors’ walled city. In this respect, Romero was actually ahead of the curve.

The Wikipedia entry for “Zombie Video Games” lists around 150 titles released since 1982, half of which came out between 2005-2013. To be clear, many of these games only incidentally qualify: though Minecraft features zombies, I’d hardly classify it as a “zombie game.” These incidental inclusions do however highlight how zombies have infiltrated popular culture beyond the usual remit of zombie apocalypse.

“Give birth” is euphemistic: as Dr. Caldwell (Glenn Close) explains to Melanie (Sennia Nanua), one of these such infected children, she and others like her don’t wait for natural childbirth but consume the mother from the inside.