Discworld Reread #1: The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic

Satirizing the fantasy of the early 80s

One of my projects this spring and summer is rereading all of Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels—in order of publication! This is something I’ve been wanting to do for some time, as a necessary component of engaging in some longer-form writing on Discworld and my own understanding of the political and social philosophy Sir Terry iteratively developed over the forty-one novels of the series. As I go, I’ll be posting some of my thoughts and observations.

They won’t all be this long, I promise! This one does some necessary table-setting, but I also found some thoughts I wanted to dig into. That will happen on occasion, but sometimes (I have to assume) I’ll just offer a recap, impressions, and a list of favourite things.

In The Colour of Magic (1983) and The Light Fantastic (1986), we meet Rincewind the failed wizard, who will go on throughout the Discworld novels to have a series of spectacular adventures he devoutly does not wish to have. In these first two novels Rincewind is given charge of Twoflower, an insurance agent from the Agatean Empire and the Disc’s first tourist: a cheerful, guileless, earnest fellow determined to see all of the sights the wide Disc has to offer. But as Rincewind tries (and fails) to impress upon Twoflower, “the sights” have a bad tendency to be situations that could kill you and are best avoided.

Needless to say, hijinks ensue and take the recognizable form of a picaresque fantasy adventure replete with dragons, wizards (actual wizards, not the Rincewind kind), bare-chested barbarians of both the himbo and femme fatale varietals, Lovecraftian Old Gods, regular mythic gods, dwarfs, trolls, dryads, pirates, a gingerbread cottage, and of course a sentient travellers trunk with several dozen tiny legs.

As Rincewind would likely say, it’s not the destination—it’s the people who try to murder you along the way.

1. Some Thoughts on Starting Here

Before I get into the novels proper, I feel it behoves me to address the perennial Discworld question: where to begin? I am starting at the beginning here and going in sequence for two reasons: (1) I want to be systematic and not haphazard about this, and (2) I want to watch Discworld develop and grow as I go.

But then, this is not the ideal way to approach Discworld if you’re just starting.

There are forty-one novels in total, but even though we refer to the Discworld series, it’s really not. Not a series, I mean … not in the sense of being serial, at any rate, wherein each instalment picks up where the last left off, and to have a grasp on the overarching story you must begin at the beginning and read in sequence.

That is not how Discworld works. As I’ve noted in this space previously, when asked by newbies what Discworld novel to start with, the lion’s share of Sir Terry devotees emphatically recommend against starting at the beginning. All the novels are effectively standalones; though various stories develop over groups of novels, these are less narrative arcs than thematic clusters centred on places and characters. Ask a seasoned Discworlder for advice and you’re likely to receive a chart outlining the clusters:

And we all have our favourite starting points. I fortuitously fell into Discworld with a handful of ideal starters. My first was Small Gods (#13), followed fairly quickly by Night Watch (#28), Wyrd Sisters (#6), and The Fifth Elephant (#24).1 My standard advice is that anything in the mid-range of the publication chronology—especially anything from the 1990s—is a safe bet. As my first quartet of novels indicates, I read my way through fairly chaotically, ranging back and forth almost at random (usually guided by what was on the bookstore shelf when I was in the mood for a new Discworld read). You lose nothing reading in this manner. Or I didn’t, at any rate.

Why, then, do most of us devoted Discworlders warn newcomers off The Colour of Magic (#1)? Well, I can only speak for myself—but I suspect I’m not alone in finding the first few Discworld novels … well, a little crude. Not crudely written (the prose is characteristically sharp), nor crude in terms of subject matter. But … well, perhaps unformed is the better word. It’s like looking at early attempts by a master sculptor, where you can see the shape of what’s to come, and you can see the artistry, but everything is still rough around the edges. Were you to pick up The Colour of Magic or The Light Fantastic with no expectations, it’s a pretty decent chance you’d enjoy them and find them funny—hilarious, even—sendups of fantasy. But if you come to these early novels with all the expectations that attach to everything you’ve heard about Discworld from people like me? There’s a better-than-even chance your response would be meh.2

That’s because Discworld comes into increasingly sharper focus as the novels proceed. The Discworld series is not serial, but it does grow and evolve—both in terms of our increasingly nuanced understanding of the world, and in terms of its characters’ development and maturation. Each story at once builds out and refines the world—its logic, its geography, its laws both natural and human-created, its peoples, and above all its characters and the societies they make. This last element is crucial and, as I will argue as this reread series progresses, what ultimately makes Discworld something more than riotously funny and engrossing fiction. As the novels progress, they come to collectively articulate a nuanced and profound social and political philosophy.

Sir Terry took inspiration from Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, thinking to do with fantasy what Adams did with SF. As I’ll discuss momentarily, The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic fondly but sharply take the piss of fantasy. In the early 1980s the genre had become somewhat sclerotic, leaning more into its pulpy origins, aping Tolkien’s verbiage but settling into rote derivations of generic conventions. The Colour of Magic’s whole schtick is parodying these conventions. So too is The Light Fantastic … but to a very slightly lesser degree. With Equal Rites (#3) we start to see Sir Terry leaving the straight-up satire and putting some meat on the bone.

(But I’ll have more to say about Equal Rites in my next Discworld reread post).

2. Unformed Clay

I first read The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic late in my journey through Discworld, specifically because I had been warned to hold off until I had a critical mass of the novels under my belt. I immediately saw the wisdom of that advice, as I was underwhelmed. Upon rereading them, I’ve revised that initial evaluation a bit—but I’ll get to that below.

This is only the second time I’ve read these first novels. Some Discworld books I’ve returned to many, many times—in some cases it’s because I’ve taught them (Witches Abroad, Small Gods), but often because they are comfort reads that I return to when the world is too much with me (most notably, The Fifth Elephant, Hogfather, The Truth … and also Small Gods and Witches Abroad). I read The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic in part for the sake of completing the set, as it were. And because, whatever else they are, they were once upon a time that increasingly precious commodity: unread Discworld novels.

So, before I dive into my Thoughts, a few thoughts. As I advance through this reread, I’ll take note of Firsts: the first time we encounter a recurring character, theme, place, setpiece, etc. As I’ve said before, Discworld is an iterative world—by which I mean, each novel offers a new spin on a set of established conventions that fleshes the world out, refines it, introduces new elements, and serves to further articulate what becomes the emerging, overarching philosophy of Discworld. So it’s interesting to see how these early novels assay into as-yet uncharted territory.

The Disc: The most obvious first encounter here is with the Discworld itself in all its absurdist glory, the ten-thousand-mile-wide disc resting on the backs of four ginormous elephants (Tubul, Jerakeen, Berilia and Great T'Phon), who themselves stand on the back of Great A’Tuin, the cosmic turtle.

Rincewind: This is also our first encounter with one of the Discworld’s most beloved recurring characters, who features in eight novels.3 He is the epitome of the reluctant hero: having effectively flunked out of Unseen University, he nevertheless wears a wizard’s garb, and just to make sure he’s not mistaken, he has “Wizzard” picked out in letters on his pointy hat. We learn in The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic that the reason for his failure as a wizard was that one of the eight spells in The Octavo—the most powerful book of magic on the Disc—lodged in his head when he was a student, to the exclusion of anything else magical. At the end of The Light Fantastic he is able to get rid of the spell and the suggestion is made that he’ll return to his studies … but mercifully, that doesn’t seem to happen and he returns as his normal hapless self.

Death: Death is such a staple of the Discworld novels that I probably don’t need to say much here, other than that he takes a particular interest in Rincewind—who has apparently eluded his final destination a few times before we meet him, and the Grim Reaper is getting impatient.

The Luggage: Easily one of Sir Terry’s most popular creations: Twoflower arrives with a travellers chest built of sapient pearwood, and exceptionally valuable magical material. The Luggage has seemingly endless magical properties, not least of which are its vast internal capacity, its indestructability, its sentience, and the dozens of tiny legs it sprouts. At the end of The Light Fantastic, Twoflower gifts the Luggage to Rincewind, and it follows him through all of his subsequent adventures. While Sir Terry attributes the origin of the Luggage to seeing “a very large American lady towing a huge tartan suitcase very fast on little rattly wheels which caught in the pavement cracks and generally gave it a life of its own” (Sourcery dedication), it has also been pointed out that the Luggage bears more than a passing resemblance to Mimics in D&D—shapechanging monsters that frequently take the form of treasure chests in order to lure in unwary adventurers.4

Ankh-Morpork: The greatest—or at least the loudest, stinkiest, most populous—city on the Disc. Bisected by the serpentine, sludgy, and probably toxic River Ankh, it bears closest resemblance to London, if we can imagine contemporary London’s ethnic and racial diversity conflated with Dickensian London’s squalor. As Sir Terry iteratively builds out the Discworld, he returns quite frequently to Ankh-Morpork (especially in the Watch novels), and the city becomes a character unto itself. We only get the slightest hints of what’s to come, mostly in the form of the city’s most dangerous and venal inhabitants. Eventually, however, I will have a lot to say about the way Ankh-Morpork becomes a vehicle for Sir Terry’s philosophical pragmatism, especially as embodied by the city’s leader:

The Patrician: Eventually we meet Sir Terry’s idealized Machiavel, Havelock Vetinari, the austere and brilliant city Patrician whose principal mode of governance is to balance all of the city’s myriad self-interested groups and individuals against each other in such a way that Ankh-Morpork effectively governs itself. The Patrician we meet in The Colour of Magic ain’t Vetinari—whether he’s just an early draft of the later character or a leader who precedes Vetinari is not a detail I currently recall, but we do see the broad strokes of his ruthless mastery of intelligence. However, anybody reading the later novels who becomes familiar with Vetinari’s ascetic character will recoil to read here that “The Patrician cradled his chins in his beringed hand …” (41).

Cohen the Barbarian: I’ll have more to say about him below.

Unseen University: The Disc’s premiere school for magic. As the novels proceed, UU will become (to my mind at least) the funniest and shrewdest satire on academic life in a world lousy with satirical campus novels. Speaking as a professor of twenty years, it’s a rare departmental meeting where I don’t hear echoes of Sir Terry’s wizards in my and my colleagues’ idiosyncrasies. It’s odd to feel both seen and attacked. We only get a few hints here of the personalities that will become more developed, but the shape is there in the unformed clay.

The Librarian: Ook! Eventually, Sir Terry will settle into a stable cast of characters at Unseen University, but here at the outset the magical academicals are unfamiliar to anybody who’s read widely in the middle-range of Discworld prior to finding their way to the origins. With one exception: the Librarian, the wizard who had been turned into an orangutan and resisted all his colleagues attempts to turn him back. I had quite forgotten that we have a blink-and-you-miss-it origin story for the Librarian in the early pages of The Light Fantastic. When the Octavo, the original book of magic at the center of the novel’s story sends a blast of fire up through the ceilings of successive floors of the university, the Librarian is caught in the explosion: “several of the wizards later swore that the small sad orang outang sitting in the middle of it all looked very much like the head librarian.” Of course, as the novels proceed, the Librarian gets much less sad and much larger. But we’ll save that for future posts.

Magical Technology: One of the recurring features of the Discworld novels is the replication of Roundworld (i.e. our world) technology, but effected by way of magic. In The Colour of Magic, Twoflower—the Disc’s first tourist—comes equipped with a camera of a sort we’ll see again in future novels. The iconograph (as it’s called) is a square black cube containing an imp who paints whatever image appears through the lens. The imp also occasionally pokes his head out the side of the box in order to smoke a cigarette or make snarky comments. The iconograph also comes with an attachment for when it’s dark—a glass box of salamanders who explode in light when startled.

As this series proceeds, I’ll start including categories like “best footnote” or “favourite quotations.” As this post promises to be longer than most, I’ll refrain from further listicles. I will note however that, while until now I’d only read The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic once previously, there is one passage from the latter that I’ve often quoted in my first-year classes when discussing the distinction between literal and figurative language. It’s a lengthy passage, so I won’t quote it in its entirety. I’ll suffice with: the former Patrician of Ankh who passed a law prohibiting figurative language “was eventually killed by a disgruntled poet during an experiment conducted on the palace grounds to prove the disputed accuracy of the proverb ‘The pen is mightier than the sword,’ and in his memory it was amended to include the phrase ‘only if the sword is very small and the pen is very sharp’” (19).

Sadly, whenever I quote this passage, my students don’t really laugh but look sidelong at each other in confusion.

3. The 80s Fantasy of It All

Returning to them for the first time in … conservatively? Over ten years, at least … is instructive. For one thing, they’re both better than I remember, probably because my expectations are different. The most interesting thing to me is seeing Sir Terry working stuff out—they’re both obviously first drafts of what becomes the Discworld project—but also to consider more carefully the kind of parody at work. I’ve long said that Discworld starts as a straight-up pisstake, a sort of Hitchhikers Guide to Sclerotic Fantasy. But on returning to The Colour of Magic in particular, what’s interesting is seeing what kind of fantasy is having the piss taken.

Because, really, it’s about what fantasy looked like in 1983.

Fantasy as a genre is far more complex than a casual perusal of cover art5 or titles6 at your local bookstore might suggest: it has a complex genealogy, one major branch of which emerges from ancient mythology, legend and folklore, and fairy tales. If it has one central shaping influence, it’s medieval romance (which is itself indebted to the aforementioned story traditions)—especially as translated through the narrative nexus of J.R.R. Tolkien’s writing and myth-making.7

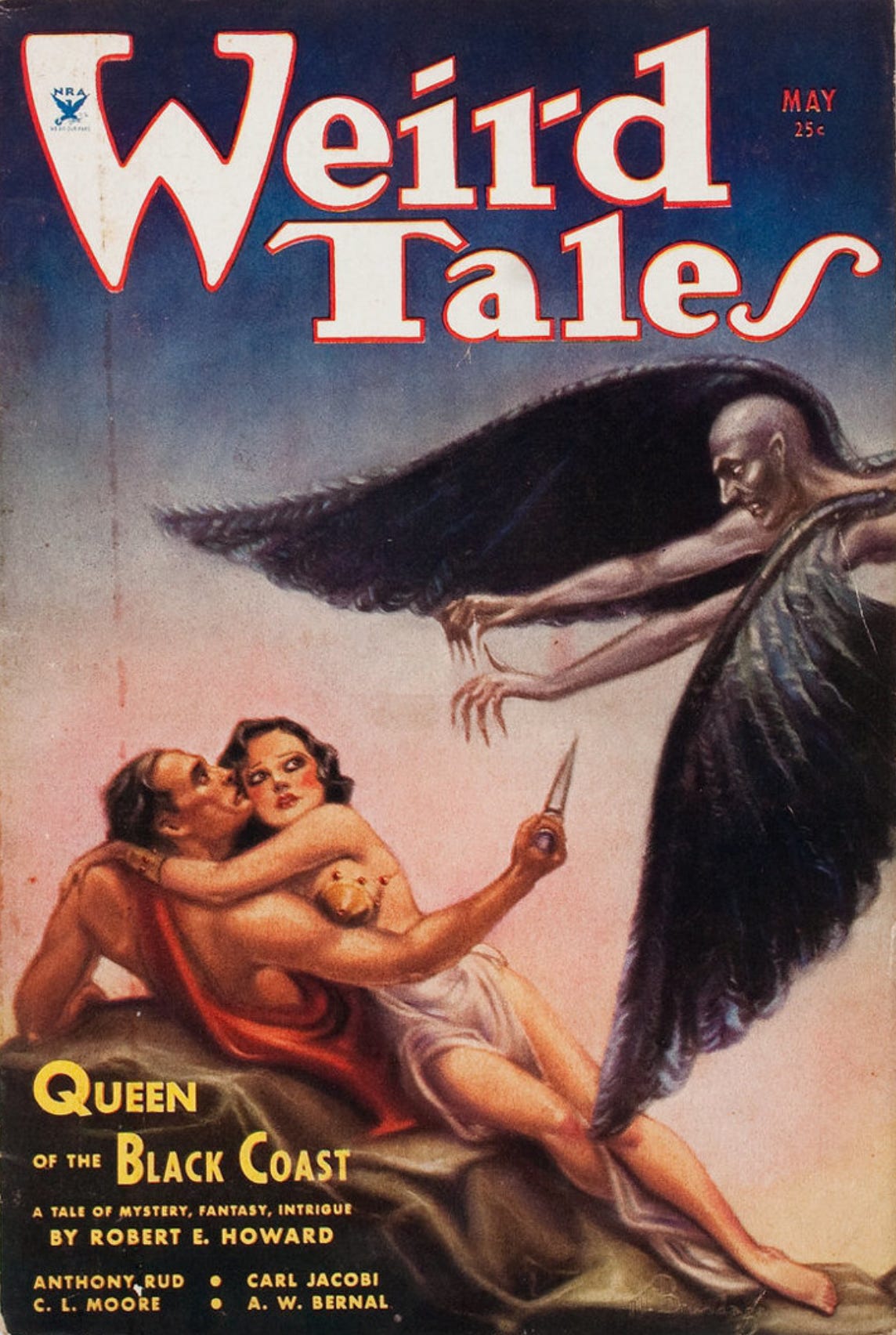

All of which is by way of saying: that’s (mostly) not the fantasy Sir Terry parodies in these first two novels. The other prominent branch in fantasy’s genealogy emerges from the pulp magazines of the 1920s and 30s. To oversimplify for the sake of, well, simplicity, this strain is essentially a conflation of Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft, with the former’s lurid neo-medieval settings and adventures featuring such heroes as Kull the Conqueror and Conan the Barbarian and their encounters with a panoply of wizards, warlocks, damsels, and savage peoples; and the latter’s occult and monstrous weird.

The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic are more preoccupied with this more lurid, sensationalist kind of fantasy most obviously epitomized by such early 1980s films as Conan the Barbarian (1982), The Beastmaster (1982), Fire and Ice (1983), and Red Sonja (1985).8 The narratives of these films replicate the diegetic logic of medieval romance and fairy-tales, combined with a sort of softcore/hallucinogenic sensibility and aesthetic. They feature bare-chested, muscular adventurers and their female equivalents in chain mail bikinis, along with lascivious witches, sylphlike princesses in need of rescue, and a host of monsters of both the human and non-human variety in need of vanquishing. These heroes sally forth through wild and unmapped land in which they can and do encounter any and all varieties of danger and adventure … which is not unlike your average medieval romance or Arthurian quest, but with a lot more oiled and/or sweaty skin on display.

There’s a whole other essay to be written here on the evolution of fantasy along the parallel tracks of lurid pulp fiction and staid Oxfordian medievalism—with, to be sure, a great deal of track-jumping along the way, not least of which is exemplified in the prog rock / heavy metal love of Tolkien and its overlap with the development of Dungeons & Dragons (which was first published in 1974) and the influence of all of the above on the aforementioned films—but that’s for a future post. For now, it suffices to note that a critical mass of post-Tolkien fantasy had calcified into a formulaic, sclerotic rut. Much of the published fiction was profoundly derivative of Tolkien, aping his verbiage but not his intellect or vision.9 And the films such as mentioned above tended to resemble the cover art of Weird Tales come to life.

Taken together, The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic comprise a cohesive narrative, with the latter novel tying together most of the narrative threads introduced by the former. The Colour of Magic isn’t itself a single story, but four connected novellas.10 In the first (“The Colour of Magic”), Rincewind encounters Twoflower and is charged by the Patrician with keeping him safe; but because Rincewind and Twoflower are both inadvertent chaos agents, they end up fleeing Ankh-Morpork when their misadventures lead to the city going up in flames. The fourth story (“Close to the Edge”), brings the companions to the rim of the Discworld, and they end up being launched over the edge in a rudimentary spaceship—which is where the novel ends and The Light Fantastic begins.

It is however in the second and third stories (“The Sending of Eight” and “The Lure of the Wyrm”) that we find the most pointed satires on the Weird Tales branch of fantasy’s family tree. In “The Sending of the Eight,” Twoflower ambles his touristy way—keen to see all the sights—up an old path in the woods into an ancient temple decorated with many engravings and bas-reliefs of a tentacular creature. What follows is an encounter with a Lovecraftian god named Bel-Shamharoth, into whose temple they’ve trespassed. When they accidentally wake the malevolent entity, it explodes through a hole in the floor as a mass of grasping tentacles and, finally, an unspeakable Eye.

This eldritch horror is dispensed with when Rincewind, having taken hold of Twoflower’s iconograph, sets off the salamanders in a “flash of light so white and so bright … Bel-Shamharoth screamed, a sound that started in the far ultrasonic and finished somewhere in Rincewind’s bowels” (135).11

Also venturing into the temple is Hrun the Barbarian. His endless search for treasure and adventure lead him to follow the Luggage up the forest path, and he ends up battling Bel-Shamharoth alongside Rincewind and Twoflower (though the latter two don’t do much in the way of “battling,” in truth). Hrun is a comic distillation of the sort of sword-wielding bodybuilder ubiquitous in fantasy cinema in the early 80s: “Observe Hrun, as he leaps cat-footed across a suspicious tunnel mouth. Even in this violet light his skin gleams coppery. There is much gold about his person, in the form of anklets and wristlets, but otherwise he is naked except for a leopardskin loincloth” (123).12

Hrun ends up joining Rincewind and Twoflower (though he’s somewhat ambivalent about it), as they journey into the territory of the Wyrmberg—a floating upside-down mountain that is home to a society of dragon riders.13 Long story short: they are taken captive, and Hrun is pressed into service by Liessa the Dragonlady in her quest to take the throne from her two brothers. In exchange for his help, she offers him marriage and all the wealth and power that would come from that. And there’s also Liessa’s personal charms, in which she epitomizes a certain type of warrior heroine that tended to appear alongside cinematic barbarians: “She was wearing the same sort of leather harness that the dragonriders had been wearing, but in her case it was much briefer. That, and the magnificent mane of chestnut-red hair that fell to her waist, was her only concession to what even on the discworld passed for decency” (176).

What’s so interesting to note on returning to these first Discworld novels is how quickly Sir Terry switches gears from straight-up parody to something sharper and, ultimately, funnier in his depiction of the fantasy barbarian. The Colour of Magic communicates a clear sense of just how tired and predictable certain fantasy tropes had become when Twoflower asks Hrun “What happens next?” At this point, having been separated from Rincewind, the two are locked in a cell in the Wyrmberg. This fact seems to bother Hrun not at all. He replies to Twoflower in a bored tone,

“I expect in a minute the door will be flung back and I’ll be dragged off to some sort of temple arena where I’ll fight maybe a couple of giant spiders and an eight-foot slave from the jungles of Klatch and then I’ll rescue some kind of princess from the altar and then kill off a few guards or whatever and then this girl will show me the secret passage out of the place and we’ll liberate a couple of horses and escape with the treasure.” Hrun leaned his head back on his hands and looked at the ceiling, whistling tunelessly. (174)

Twoflower is as nonplussed in this moment as an oblivious tourist gets. “All that?” he asks. “Usually,” Hrun shrugs.14

In The Light Fantastic, we see Sir Terry already starting to tinker with his parody. Hrun, having dispensed with Liessa’s brothers and dropped (literally) in her lap, is left to whatever connubial bliss his instincts will allow. But we’re not done with barbarians! Rincewind and Twoflower soon meet a legendary Discworld warrior, who is by this time somewhat long in the tooth. When Twoflower—against Rincewind’s better advice—attempts to rescue a maiden from ritual sacrifice by druids, he finds himself rescued from what would have otherwise been an ill-fated endeavour:

By the light of the torches he saw that it was a very old man, the skinny variety that generally gets called “spry,” with a totally bald head, a beard almost down to his knees, and a pair of matchstick legs on which varicose veins had traced the street map of quite a large city. Despite the snow he wore nothing more than a studded leather holdall and a pair of boots that could have easily accommodated a second pair of feet.

The two druids closest to him exchanged glances and hefted their sickles. There was a brief blur and they collapsed into tight balls of agony, making rattling noises. (99)

And in this moment we meet Cohen the Barbarian, “one of the Disc’s greatest legends” (97). Rincewind is somewhat nonplussed when he identifies himself: “Hang on, hang on … Cohen’s a great big chap, neck like a bull, got chest muscles like a sack of footballs. I mean, he’s the Disc’s greatest warrior, a legend in his own lifetime. I remember my grandad telling me he … my grandad …” Rincewind then “falter[s] under the gimlet gaze” as realization sinks in. “Thatsh right, boy,” Cohen responds, his words slurred because he has no teeth, “I’m a lifetime in my own legend” (104).

What’s worth noting here is how Sir Terry in these early novels takes the piss of the more risible fantasy conventions of the moment, but we can already see the ways in which he’s playing with them. Hrun is parody by exaggeration; Cohen is parody by defamiliarization, and is—in the spectacle of an arthritic eighty-seven year old man in a leather loincloth performing Conan-esque feats—at once funnier and a sharper critique of the absurdity of the tropes that have become de rigeur in the genre.

It will be a few novels before Discworld really hits its stride (my usual take on this point is that we get there with Wyrd Sisters, which is #6, but we’ll see if I still think that in a few posts’ time), but we can see the sculptor shaping the clay already—something that will become more evident with Equal Rites.

REFERENCES

Pratchett, Terry. The Colour of Magic. Corgi, 1983.

---. The Light Fantastic. Corgi, 1986.

Wilkins, Rob. Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes. Doubleday, 2022.

NOTES

All of which I read within the space of a little over a week, which is representative of two things: (1) how quickly I was absorbed into Sir Terry’s world, and (2) the fact that Discworld novels are basically like crack for fantasy readers of a certain mindset. Newbies, be warned: Discworld is addictive. Unlike most addictions however it is good for your health. Or your mental health, at any rate.

In his lovely biography of Sir Terry, Rob Wilkins notes of The Colour of Magic that “Terry would outgrow it, of course. He would write far better books, books with ‘discernible plots’ in them, and come to regard his first try-out for the series almost as if it were juvenilia … As Terry said in the speech he gave as Guest of Honour at the 2004 World Science Fiction Convention in Boston: ‘I find it now rather embarrassing that people beginning the Discworld series start with The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, which I don’t think are some of the best books to start with. This is the author saying this, folks. Do not start at the beginning of Discworld’” (194).

Besides The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, Rincewind appears in Sourcery (#5), Faust Eric (#9), Interesting Times (#17), The Last Continent (#22), The Last Hero (#27), and Unseen Academicals (#37).

As indeed the Luggage does to Hrun the Barbarian, after a fashion. When Twoflower has ambled up the forest path to the temple of Bel-Shamharoth, the Luggage apparently decides his owner requires some assistance of the heroic variety, which is why “earlier in the afternoon, [Hrun] had espied a chest at the side of the track while riding through this benighted forest. Its top was invitingly open, displaying much gold. But when he had leapt off his horse to approach it the chest had sprouted legs and had gone trotting off into the forest, stopping again a few hundred yards away” (122).

To be fair, cover art today is much better than what I remember. Once upon a time the critical mass of fantasy art tended to include at least one buxom warrior princess in a chain mail bikini or sylph-like sorceress in a diaphanous gown, usually fighting or embracing a barbarian or knight with Schwarzeneggerian musculature, often irrespective of what was actually contained in the story. There’s a whole essay to be written here on Paul Kidby’s Discworld cover art as its own hilarious pisstake on this particular convention.

The “The Something of Something(s)” title convention has always been overdone in the genre, quite possibly one of the legacies of The Lord of the Rings. There does seem to be a rather pervasive embellishment in recent fantasy, which a grad student in our program drily characterized as “A Noun of Nouns and Nouns.”

Among others. We can add to that list not just more self-consciously “high” fantasy offerings as Excalibur (1981) and Ladyhawke (1985), but also such children’s cartoons as He-Man and the Masters of the Universe (1983-1985), which rather disturbingly gave all its male characters Mr. Universe physiques and all the female characters centerfold bodies.

Yes, I’m painting with a broad brush. There are of course exceptions, and there are also examples of fantasy that, even though it’s doing nothing new, is nevertheless gripping and compelling.

It is in this respect unusual among the Discworld novels, which otherwise tend not to have paratextual subdivisions like chapters. Sir Terry was generally antipathetic to what he saw as artificial and arbitrary sectioning of narrative, preferring the story to happen as more of an organic flow. There were exceptions: Pyramids has section divisions, and Going Postal (#33) and Making Money (#36) adopt a sort of late-19th century affectation of offering a brief synopsis of chapters’ contents at the beginning. Perhaps most famously, Sir Terry grudgingly acceded to his editors’ demands that his YA Discworld novels be broken into digestible chapters—the better for parents to have an obvious pause in reading to their kids at bedtime.

Not unpredictably perhaps, the resulting image features a truly excellent closeup of Rincewind’s thumb.

In case we’re missing the obvious allusions to Conan, Hrun introduces himself as “Hrun the Chimerian,” obviously echoing “Conan the Cimmerian.”

The dragons in The Colour of Magic aren’t strictly speaking corporeal, but take on physical form based on the strength of a person’s imagination. It’s an interesting little quirk here, but it’s a sensibility that becomes more prominent as Discworld evolves.

Though this prediction is not borne out, Hrun still vanquishes Liessa’s coterie of guards: “He brought one are around expansively, and the wooden bunk was at the end of it. It cannoned into the bowmen and Hrun followed it joyously, felling one man with a blow and snatching the weapon from another. A moment later it was all over” (179). There is a pause, and when Liessa asks if he now plans to kill her, he says “What? Oh no. No, this is just, you know, kind of a habit. Just keeping in practice. So where are these brothers?”

Interesting observations, and I'll look forward to reading more as you progress.

I myself read all of the books in their order of publication, simply because I was already a bookseller (and stocked _The Dark Side of the Sun_ and _Strata_), and indeed had met Pterry at SF conventions, before _The Colour of Magic_ was published, so I simply bought each new book as it became available.

You may like to know (if you don't already) that years before he began publishing novels (ignoring his early juvenile _The Carpet People_, later rewritten) Pterry wrote dozens of short stories for children, under pseudonyms or anonymously, that were published in the regional UK newspapers he worked for, such as the _Bucks Free Press_. In recent years several volumes' worth of these have been identified and published. A number of the stories have elements that would later resurface in Discworld, and even more are set in various versions of the 'Blackbury' of his Johnny Maxwell and Truckers series.

I was just in a bookshop last week that actually had its wall of Pratchetts arranged according to that chart. I myself started Discworld with _The Last Hero_ (I'd had the _Truckers_ trilogy before that) but I often recommend _Going Postal_ on the grounds that it gives you a fresh start while he's at the peak of his ability.