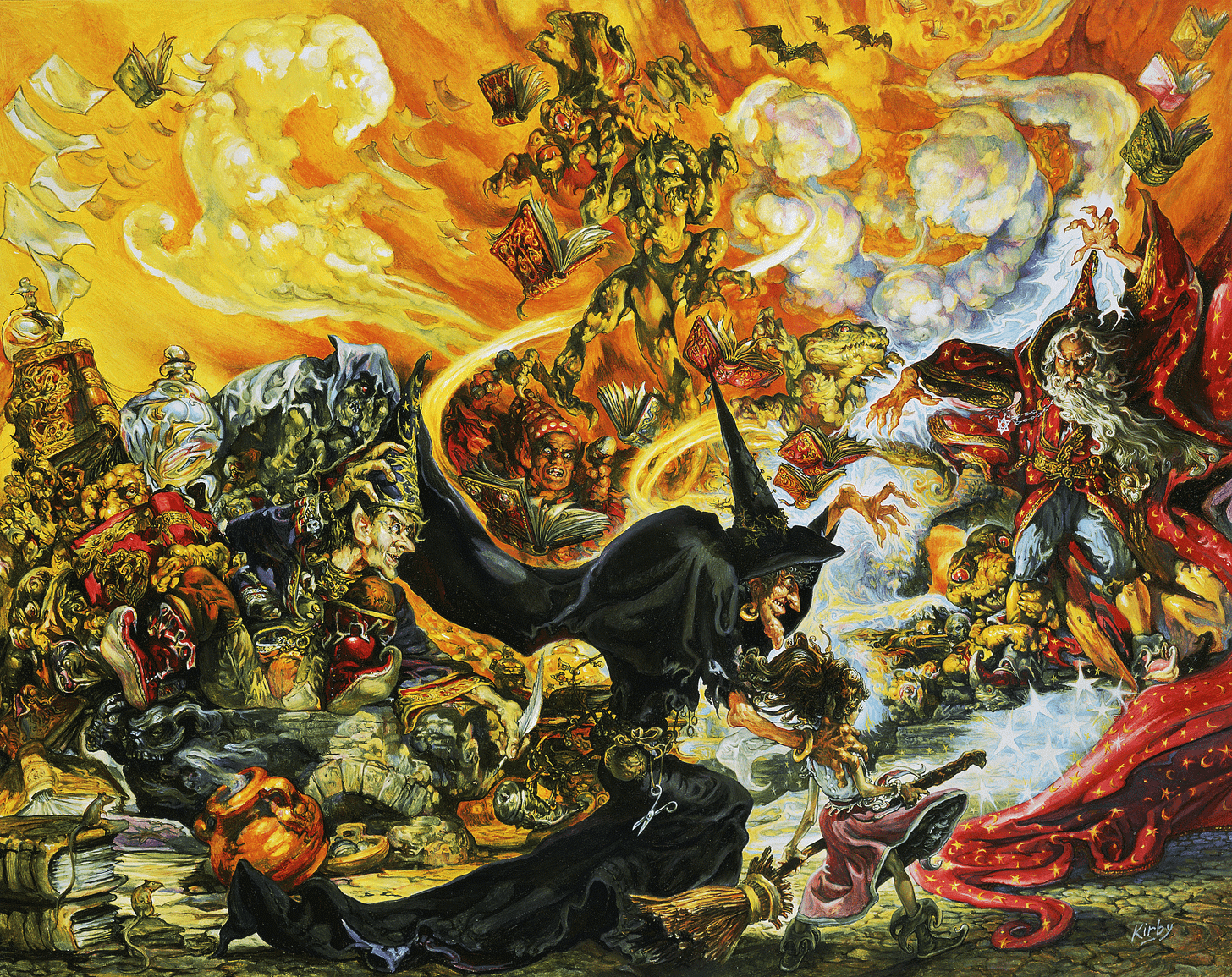

Discworld Reread #2: Equal Rites

Witches, wizards, and the knottiness of sex.

This summer I have set myself the happy task of rereading all forty-one of Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels and writing about it as I go. For me, this exercise serves a larger purpose: I have long wanted to engage in a long-form study of Sir Terry’s fiction and the social and political philosophy that he ultimately articulates. But I’ve always been hampered by the simple logistical fact that, if I’m really serious about it, I need to systematically reread all his work and get my thoughts down with something resembling coherence. So after several years of nibbling around the edges, I’m taking the plunge, and using my shiny new Substack as motivation. Please join me for the adventure!

During a portentous thunderstorm, a wizard makes his way through the darkness to a small village with the unlikely name of Bad Ass. There he seeks out a newborn child—the eighth son of an eighth son, which heralds the entry of a wizard into the world. With his last breath he gives his staff to the baby, passing on his wizarding legacy.

But wait! The infant is not, as the wizard assumed, a male child. But the deed has been done, which will upend the longstanding and ironclad custom: men are wizards, women are witches, and never the twain do meet. Except that now … well, the baby’s got the staff! And the staff seems to have taken to the baby. It is a pickle.

Fortunately for the child, who is named Eskarina—“Esk” for short—she has the ideal mentor living in the village. Granny Weatherwax takes Esk under her wing to teach her the ways of witchery and magic, but when it becomes obvious that the circumstances of Esk’s birth are manifesting in ways troubling and unfamiliar to Granny, the decision is made—the two of them will travel from the village high in the Ramtop Mountains to the sprawling city of Ankh-Morpork and Unseen University, the center of (male) magical lore.

In Equal Rites (1987), we meet the character who is, to my mind, Sir Terry’s greatest achievement. I suppose everybody has their favourites, and there are definitely a good number of characters crowding the top tier. But for me, Esmerelda “Granny” Weatherwax is the apex.

1. Unformed Clay

Much like The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, Equal Rites is set in a Discworld that is still under construction—the shape of it identifiable in the unformed clay, which will eventually take more precise form with each sculpting session. One such refinement we already see at work is the way in which this novel’s satire is more substantive: not just taking the piss of fantasy’s tired and formulaic conventions, but pointing to the ways in which some of those conventions are reflective of broader social considerations.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but Equal Rites is very much a feminist novel. As the title’s pun might suggest … and as the opening paragraphs make clear, in case you weren’t paying attention:

This is a story about magic and where it goes and perhaps more importantly where it comes from and why, although it doesn’t pretend to answer all or any of these questions.

It may, however, help to explain why Gandalf never got married and why Merlin was a man. Because this is also a story about sex, although probably not in the athletic, tumbling, count-the-legs-and-divide-by-two sense unless the characters get totally beyond the author’s control. They might.

However, it is primarily a story about a world. Here it comes now. Watch closely, the special effects are quite expensive. (11)

A novel about magic. And sex, though probably not in the rumpy-bumpy sense of the term—which means sex in the sense of gender, which further means that, should it come under the scrutiny of the current U.S. regime, it might find itself disappeared, because D.E.I.1

But more on that as we go.

I said in my initial post that in each of these instalments I’ll take note of firsts—the first time we encounter a recurring character, place, theme, or convention. But there’s not actually a lot here! The major first is of course Granny Weatherwax herself, and I’ll devote a lot of attention to her in a moment. The second half or so of the novel takes place in Ankh-Morpork, which we’ve already seen, and Unseen University, which also featured prominently in The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic. None of the wizards who appear will reappear in later novels (I don’t think).

Interestingly, Eskarina does not reappear; neither, unfortunately, does Sir Terry’s investigation of the gendering of magic.

[EDIT: I’ve already been informed by two readers that Esk does return! I don’t want to know which book, so don’t spoil it—I want to be surprised.]

Aside from Granny Weatherwax herself, the most significant lump of unformed clay in Equal Rites is the place where we begin—a small village in the Ramtop Mountains. In Wyrd Sisters, this part of the Discworld is identified as the Kingdom of Lancre, which features prominently in numerous novels to follow. Here, in the hamlet of Bad Ass, we see the basics that will be present in the witches’ novels: small, tight-knit communities, in which the blacksmith’s forge is central as a meeting place and general focus of sociality; the witch (and later, witches) plays the role of midwife, healer, and moral arbiter. Starting with Wyrd Sisters, the novels tease out a comic but subtle political framework where patrilineal monarchy sits at an intersection with parochial democratic sensibilities.

We see these elements starting to be sketched out in Equal Rites, though the societal circle in Bad Ass is kept quite small—just Granny and Esk’s family at first—such that when Granny and Esk first arrive in the neighbouring town of Ohulan Cutash, it feels like a teeming metropolis by comparison.

The other big lump of unformed clay is the nature of magic itself, which is best explored through a consideration of …

2. Granny Weatherwax

When I read Equal Rites for the first time, it was jarring to encounter Granny as a lone witch. From Wyrd Sisters (#6) on, she is the top point of a witches’ triad that includes the cheerfully profane Nanny Ogg, and the young and earnest Magrat Garlick. They comprise the witches of the “Witches” cluster of Discworld novels.2 Like many of Sir Terry’s creations, the three witches are a cliché—a variation on the triple goddess archetype, and the mother, maiden, crone troika—that the novels proceed to defamiliarize in hilarious and critically insightful ways.

But we’ll get to that with Wyrd Sisters.

For now, it’s worth noting that encountering Granny Weatherwax as a solo agent, after having first read all the other witches novels, is ever so slightly disconcerting … almost to the point of being uncanny. Unlike Rincewind in The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, who remains effectively unchanged throughout his iterative appearances, the Granny Weatherwax of Equal Rites is very much a first draft. Even so, she is very identifiably Granny Weatherwax:3 tall, thin, clad in black with a very impressive hat that functions as a badge of office, witch-appropriate warts, heavy boots that rarely leave her feet, a suspicious parochialism, and a stern, forbidding demeanour4 that only partly masks a compassion for her fellow mortals as deep as the sea.

This compassion, which manifests in a profound empathy, marks all of Sir Terry’s protagonists to a greater or lesser extent, but Granny is to my mind the exemplar. She will at various points articulate the foundational tenet of Sir Terry’s humanism: that the root of evil lies in seeing people as things. We’re in the early stages of Granny’s evolution, but the basic elements of that philosophy are present—perhaps most significantly in how she understands magic and attempts to teach it to Esk.

Magic in Discworld becomes somewhat attenuated after the first few novels: it is less something its practitioners do and more a general law of nature. In these early entries, magic is about as spectacular as it gets, arguably culminating in the “sourcerer” Ipslore in Sourcery; but from that point, Sir Terry becomes less interested in displays of magical prowess on the part of his witches and wizards5 and more interested in what Granny Weatherwax calls “headology.”

In Granny’s early tutelage of Esk, the girl becomes impatient with the lessons, which “were quite practical. There was cleaning the kitchen table and Basic Herbalism. There was mucking out the goats and The Uses of Fungi. There was doing the washing and The Summoning of the Small Gods” (57). Frustrated, Esk protests, “But it’s not magic!” (58). “Most magic isn’t,” Granny responds. “It’s just knowing the right herbs, and learning to watch the weather, and finding out the ways of animals. And the ways of people, too.” Reading these exchanges in Equal Rites for the first time gave me a strong “wax on/wax off” vibe, but—because I was by then quite familiar with the character Granny Weatherwax becomes—it was deeply satisfying to read. When Esk later observes that Granny knows a lot of things, Granny replies, “Exactly correct. That’s one form of magic, of course” (59).

In fact, it’s headology. Which is not to be confused with psychology (though I suppose the Venn diagram would have some overlap). When Esk says, incredulous, “What, just knowing things?” Granny corrects her: “Knowing things that other people don’t know.” A great deal of magic, Granny makes clear, is about perception. People’s belief is as important as any other factor: “if you want it to work for sure then you let their mind make it work for them” (62), she instructs Esk. “That’s the biggest part of doct’rin,6 really. Most people’ll get over most things if they put their minds to it” (63).

One can debate the efficacy of the placebo effect or roll one’s eyes at the apparent new-agey woo-woo of “the power of positive thinking,” but I’d gently suggest that’s too literal a reading.7 A key element of Discworld’s magic is that thought and imagination, especially collective thought and imagination, has affect—which is to say, it brings the products of mind into physical being. In the opening pages of Equal Rites, when we’re introduced to the Discworld, the very existence of the cosmic turtle is cited as a predicate for this relationship between thought and reality: “It is Great A’Tuin, one of the rare astrochelonians from a universe where things are less as they are and more like people imagine them to be” (11-12).

With Equal Rites we’re still in the early stages of working through the natural laws and magical properties of Discworld, but the direction the novels go is discernible from what we see on the pages here.

Magic as a general property is what holds the Discworld together, given that a massive disc on the back of four ginormous elephants who themselves stand on the back of a cosmic turtle require something more than your basic Roundworld physics. It is a world in which, to quote a minor Irish poet, a thing must be believed to be seen: we haven’t yet arrived at the premise that Discworld gods exist as a function of peoples’ belief, but we see the first glimmers of that dynamic in Granny’s understanding of magic. As I noted in my post on the anniversary of Sir Terry’s death, “This contingent nature of the Discworld gods exemplifies how Sir Terry allegorizes the mechanisms of reality-building.” Which is to say: so much of our quotidian, concrete reality—money, law, national borders—is the product of collective, consensual fictions. Not least among these fictions is the figuration of humanity itself.

This is an understanding integral to Sir Terry’s fiction, and one I’ll be returning to repeatedly in this series. The magical humanism of Sir Terry is magical precisely because it is predicated in contingent and not absolute understandings of the human.8 Equal Rites gives us hints of this in how it parses sex and magic.

3. The Engendered Discworld

As Sir Terry promises (warns?) in his opening paragraphs, Equal Rites is “a story about sex.” Well, about magic and sex.9 Well, really, about the gendering of magic that has long given us venerable bearded wizards and cackling be-warted witches. The crisis precipitating the story is a moment of misgendering, when the wizard Drum Billet mistakenly puts his magical staff10 in the hands of a newborn he thought was a boy. Given that the wizard then promptly dies, he doesn’t realize his mistake; or rather, he doesn’t realize his mistake while on the mortal coil but then bemoans the error to Death.

“I was foolish,” said a voice in tones no mortal could hear. “I assumed the magic would know what it was doing”.

PERHAPS IT DOES.

“If only I could do something …”

THERE IS NO GOING BACK. THERE IS NO GOING BACK, said the deep, heavy voice like the closing of a crypt door.

The wisp of nothingness that was Drum Billet thought for a while.

“But she’s going to have a lot of problems!”

THAT’S WHAT LIFE IS ALL ABOUT. SO I’M TOLD. I WOULDN’T KNOW, OF COURSE. (19)

Death’s reply—that perhaps the magic did know what it was doing—introduces the suggestion that the “lore” dictating the maleness of wizards and femaleness of witches is not an absolute principle, but something contingent.

The possibility that the magic knew what it was doing suggests that magic itself isn’t necessarily gendered. But then, the people who adopt and practise it are. Men have their own magical predilections and women have theirs, as Granny articulates to Esk:

“I mean there’s no male witches, only silly men,” said Granny hotly. “if men were witches, they’d be wizards. It’s all down to—” she tapped her head “—headology. How your mind works. Men’s minds work different from ours, see. Their magic’s all numbers and angles and edges and what the stars are doing, as if that really mattered. It’s all power. It’s all—” Granny paused, and dredged up her favourite word to describe all she despised in wizardry, “— jommetry.” (84)

There’s a lot to unpack here, not least being that Granny, for all her wisdom, is herself subject to certain assumptions and conventions. This much is consistent throughout the novels: she is parochial, suspicious of anything foreign—which by her lights is anything more than a day’s walk from her cottage—and considers taking off one’s boots to sleep the height of impropriety. She is certainly antipathetic to anything newfangled, be it in theory or praxis. But as I noted above, the baseline of Granny Weatherwax’s self is empathy and compassion, which at times obliges her to adapt her thinking.

As we see in this moment, Granny is as invested in the gendered understanding of magic as the wizards we later encounter at Unseen University. For Granny, however, the difference isn’t simply a question of custom and tradition, or “lore” as the wizards call it. (Indeed, she gets quite stroppy later when various wizards react negatively to her presence in their male sanctums, glaring daggers at anybody uttering the word “lore.”) Rather, Granny sees the gendering of magic as based in fundamental differences between men and women, between the ways they think and how that structures their priorities and skillsets. But before we arrive at a variation on “wizards are from Mars, witches are from Venus” sort of essentialism, let’s remember the central conflict around which this story pivots: a young woman who, in spite of the weight of convention and tradition on one hand, and putative gender characteristics on the other, proves prodigiously and dangerously talented at a magic that seems determined to ignore such distinctions.

And however invested Granny Weatherwax is in the wizards/witches taxonomy, in the end that takes a back seat to the reality of Eskarina, the human in front of her.

4. The J.K. Rowling in the Room

Perhaps the most obvious contrast to be made—or at any rate the one that in the present moment begs to be made—is with the wizards and witches of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels. Perhaps most salient in this contrast is the way in which Rowling’s world-building effectively flattens difference. There is a certain blandness inherent in the carefully diverse, explicitly heteronormative,11 vaguely Christian-conforming world,12 exemplified by the fact that “wizard” and “witch” function as gendered nomenclature rather than indicating any actual difference between the two designations. Men and women move between societal roles with no gender-based impediments—ostensibly, a progressive vision of an egalitarian society, at least where gender is concerned.

Even without reading with the benefit of hindsight, however, gender in the Harry Potter novels appears as entirely frictionless.13 Boys and girls live in gender-specific dormitories, go through the sturm und drang of puberty with all the drama but none of the actual messiness, and generally get married quite young and have small families of few children.14 And if there’s little friction in gender, there’s none in the way magic manifests in individuals: “witch” and “wizard” mean about as much as “Mrs./Ms.” and “Mr.”

Perhaps appropriately for a novel declaring its preoccupation with sex and magic, Equal Rites is all about friction. (Though again, not the fun kind. Probably.) The conceit at the heart of the novel isn’t about the illusion of difference preventing women from being wizards, but the fact of difference giving rise to the different practices of magic, and also that these differences aren’t absolute. There’s a permeability, as realized in Esk’s magical talent, in the distinction Granny Weatherwax draws. What makes Granny Granny is seeing past her own assumptions and seeing Esk.

By contrast, J.K. Rowling pulls off the magic trick15 of eliding male and female difference while tacitly positing it as binary and absolute.

See? Hindsight.

I’ll stop short of suggesting that Equal Rites is a trans allegory, but it wouldn’t be difficult to tease out such a reading from the novel’s premises. At issue isn’t merely a question of equality of opportunity; though the “lore” to which the wizards gesture expresses a sort of proprietary exclusion based solely on custom, Granny Weatherwax’s distinction between male and female realms of magic expresses a more nuanced understanding of difference. But as I note above, however much she may initially police the boundaries between male and female magic, Granny is open to recognizing those boundaries as permeable, or even arbitrary.

This recognition of certain intrinsic differences between men and women without seeing them as absolutes is exemplary of the nuance underpinning Sir Terry’s fiction. Ultimately, that nuance proceeds from a basic recognition: human beings are messy creatures and have an annoying tendency to resist taxonomy. Two years ago I wrote a long essay on Medium16 titled “Sir Terry vs. the Gender Auditors” whose starting point was the (ultimately failed) attempt by the “gender critical”17 crowd to posthumously claim Sir Terry as a transphobic ally.

TL;DR: wut?

I won’t rehash my argument here, but I did note at the outset that it was telling that the most common reaction from Sir Terry’s fandom was precisely that note of consternation. There was anger, to be sure, but it was largely accompanied by a sort of incredulous laughter. The refrain circulating on social media in response—most prominently from Sir Terry’s daughter Rihanna—was “read the books!”

On returning to Equal Rites, I’m a wee bit perturbed that Sir Terry leaves Eskarina behind and, with her, this exploration of magic and gender. Which isn’t to say that the broader topic is one he shies away from: as noted above, when gender fundamentalists tried to claim him posthumously, it was a failed attempt because people who had actually read Discworld closely laughed them out of the room. Still, it feels like a missed opportunity.

On the other hand, we will eventually find our way to Eskarina Smith’s heir apparent. But we’ll have to wait: we’re twenty-seven novels away from the first appearance of Tiffany Aching.

REFERENCES

Pratchett, Terry. Equal Rites. Corgi, 1987.

NOTES

During the drafting of this post I kept noodling around with a joking subtitle along the lines of “I preferred Discworld before it got woke!” but couldn’t stick the landing.

For those who like to look forward to such things: Wyrd Sisters (#6), Witches Abroad (#12), Lords and Ladies (#14), Maskerade (#18), and Carpe Jugulum (#23).

One item I left off my discussion of The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic is the odd fact that the Archchancellor of Unseen University in those first two novels is named Galder Weatherwax. My memory for details being rather less than eidetic, I can’t recall if Granny ever mentions in passing that she had a wizard relation. I guess we’ll find out. One way or another, I suppose it’s safe to assume Sir Terry just liked the name, and didn’t want it to disappear along with Galder’s ignominious exit from The Light Fantastic.

In more unformed clay: Granny’s studied, stern aspect is still a work in progress. At least once or twice she is described as “grinning”—which is more disconcerting than seeing her sans her coven of three.

As I’ll discuss when I revisit novels dealing with the wizards, the evolution of Unseen University also features a comparable attenuation of magic. The near-catastrophic events of Sourcery (#5) lead to a reorganization of the university that has the dual effect of ameliorating the potential for excessive use of magic and stabilizing the faculty of wizards into a cast of characters who function as one of the best satires of academia I’ve encountered. In effect, Sir Terry neuters wizards’ hunger for power by giving them tenure.

I quite like the fact that while this is obviously a Grannyism for “doctoring,” it can also be read as “doctrine.” In this context, their meaning can be conflated.

Never mind that Granny is the antithesis of the New Age stereotype: this much is emphasized when, in the first stage of their trek to Unseen University, she and Esk run into an old friend of Granny’s. Hilta Goatherder runs a magical tchotchke shop in the town of Ohulan Cutash that is “a mass of velvet shadows” with an “herbal scent thick enough to bottle” (97). “I would have thought,” Granny says severely, “one could carry out a perfectly respectable business, Hilta, without resorting to parlour tricks” (121). We’ll also see a more pointed (yet sympathetic) satire on earth-mother Wicca with the introduction of Magrat Garlick in Wyrd Sisters, whose newfangled ideas about witching Granny finds deeply suspect.

The most obvious example of this is the way in which the designation “human” in the Discworld novels is not species-specific in the same way Tolkien employs “Men” as a category in his legendarium. Read enough Discworld and soon enough you come to realize that “human” is a broad and inclusive category that doesn’t differentiate between humans classic™, trolls, dwarfs, gnomes, or any of the other mortal beings from the broader fantasy legendarium that populate Discworld.

Which is not to be confused with the magic of sex. Plenty of other books on the fantasy shelves dealing with that theme these days.

We’ll stick a pin in all the Freudian jokes for the moment. Presumably I’ll have an occasion in a future post to quote from Nanny Ogg’s song “A Wizard’s Staff has a Knob at the End.”

Perhaps it’s uncharitable, but I have little truck with Rowling’s post-hoc claim that Dumbledore was gay the whole time. While that possibly informed the writing of the character, it was a bit of a cheat to make the claim while all was said and done and the vast popularity of the series made Rowling more or less inured to backlash.

Though religion of any sort is effectively absent from Rowling’s world-building, all the novels save the last one follow the rhythms of the Christian year—punctuated by Halloween, Christmas, and Easter. The fact that all three of these holidays are functionally hybrids of Christian and pagan traditions could be explored from a more mythopoetic perspective, but that has to rest in scholarship and fan fiction, because there’s no such inclination in the novels.

This is not a new or novel critique of the Harry Potter novels. Though I was an avid reader of the series, reading each as soon as it came out, this frictionlessness—which applies also to Rowling’s treatment of race and the general absence of belief systems—always felt, well, easy. I think I probably attributed it to a YA fiction tendency, i.e. a glossing of spikier issues for the sake of younger readers. I’ve since revised this understanding, realizing it said more about my ignorance of YA fiction than Rowling’s writing.

Small families with at least one obvious exception. This isn’t the place to get into it, but what’s up with magical people getting married right out of high school? The most uncharitable reading, which unfortunately J.K. Rowling seems determined to court these days, is that it articulates a very traditionalist heteronormativity in which young men and women lock themselves into monogamous hetero relationships and procreate before having a chance to get distracted by other ideas about sex and gender (the absence of universities for magical folks, which is an elision that always deeply bothered me about Rowling’s world-building, becomes rather more suggestive in the context).

See what I did there?

That post was my first attempt to find my way to a new space to write stuff that fell somewhere between scholarly articles and basic blog posts. I’ve been disenchanted with academic writing for some time and had become dissatisfied with my old blog as a platform. Medium (in its very name, no less) seemed a promising middle ground, and I ended up posting five essays over the space of a year. I’m actually quite proud of them, but Medium never really worked for me. Why it didn’t while Substack apparently does is possibly the subject of a future post. In the meantime, you should check out my writing there. I think it’s pretty good, especially my Barbie essay.

I will never not put “gender critical” in quotes. As I argue in the essay, we shouldn’t allow them to be able to claim the mantle of criticism, which at its best is thoughtful, nuanced, and intellectually productive. I advocate for “gender fundamentalist,” which is a much more accurate descriptor.

Oh, this is lovely – it’s great to see someone else using Substack for process writing for a larger project! I discovered the same thing, and have no idea why Substack works so well for me for a book project (that I plan to publish as a popular/general one rather than a peer-reviewed one) when I could never get into any of blog services (LiveJournal and Dreamwidth are sort of technically ‘blogs’ but never felt like it, and a lot of the people with blogs hated LJ back in the day).

I think I agree with about 93.7% of this post! And I know you’re working through the book sin order of publication which affects a lot of what you can say (though you have some nice foreshadowing with regard to Tiffany, and the Witches sub-series).

I cannot remember what order I read Pratchett’s novels in—I know I started with _Small Gods_ as recommended by a friend of mine (who did a fantastic presentation on the wizards vs. philosophers aspect of Pratchett’s world-building), and loved it. I think I then found some of the Rincewind ones (this would have been in the middle and later 1990s (last century!), and I think it took a few more years for Pratchett’s work to start being widely available in the U.S. I remember being somewhat ambivalent about EQ the first time I read it (and I did not have consider it a feminist novel—now, I would say, it depends on how one defines “feminist”!).

And of course during the 1990s, there was a lot of discourse on “feminist” meaning “a strong female character” (emphasis on the singular! and very misogynistic focus on physical strength) that led to some interesting discussion; I still remember one hilarious take-down of the idea that a S.F.C. makes the text automatically “feminist” that was an analysis of Lara Croft’s big pixels. Bechdel coined the “Bechdel-Wallace” test in regard to movies in 1985, but I think it took a few years to become more widely known, and even then it was widely (mis)understood (if my students at the time are representative) as “if it passes the test, it’s feminist,” as opposed to “minimum to avoid being totally sexist.”

I do think that EQ was the start of Pratchett exploring and critiquing essentialist ideas of gender in his novels, and that over time, his work became feminist, and one of the reasons I describe it that way is that he didn’t focus only on the differences between wizard [man]/witch [woman] but on the differences among and between women—that is, he did what Tolkien and many other (mostly but not entirely male) authors (in many genres, not just fantasy) failed to do, moving beyond the single/token/exceptional women to show women in groups and relationships of various kinds (not just family). And while the witches are a major part of that (culminating, as you say, in the Tiffany Aching series, though I think it started with Agnes/Perdita storyline), it’s not only the witches. They get the most focus, and get to be POV characters (sometimes the groups of women are observed through a man’s eyes—thinking of Vimes observing the group of women working with Lady Sibyl to rescue dragons). And Pratchett being Pratchett, there’s no woo-woo-utopian-sisterhood established (though Magrat does seem to want a New Age version of that at times, but of course that desire runs up against Granny and Nanny; but, and I forget which book makes it clear—maybe Lords and Ladies—even though Magrat’s theory of magic differs from the others, she is a witch, and that means her magic works). But despite some reluctance, the relationships happen (Angua and Cheery).

Now that I’m thinking about it, I can hardly wait for you to talk about Thief of Time and the issue of Auditors taking on corporeal forms (mumblemumblevalaandmaiamumble), and Myria Le Jean’s narrative arc, in the context of the sexist binary of male [mind]/female [body]!

*”Misogyny” vs. “sexism” I am working to integrate Kate Manne’s definitions and “logic of misogyny” (_Down Girl_ https://academic.oup.com/book/27451?login=false) into my thinking these days!

QUOTE:

“So sexist ideology will often consist in assumptions, beliefs, theories, stereotypes, and broader cultural narratives that represent men and women as importantly different in ways that, if true and known to be true, or at least likely, would make rational people more inclined to support and participate in patriarchal social arrangements. Sexist ideology will also encompass valorizing portrayals of patriarchal social arrangements as more desirable and less fraught, disappointing, or frustrating than they may be in reality. Whereas, as I’ve defined misogyny, it functions to police and enforce a patriarchal social order without necessarily going via the intermediary of people’s assumptions, beliefs, theories, values, and so on. Misogyny serves to enact or bring about patriarchal social relations in ways that may be direct, and more or less coercive. On this picture, sexist ideology will tend to discriminate between men and women, typically by alleging sex differences beyond what is known or could be known, and sometimes counter to our best current scientific evidence. Misogyny will typically differentiate between good women and bad ones, and punishes the latter. Overall, sexism and misogyny share a common purpose-- to maintain or restore a patriarchal social order. But sexism purports to merely be being reasonable; misogyny gets nasty and tries to force the issue. Sexism is hence to bad science as misogyny is to moralism. Sexism wears a lab coat; misogyny goes on witch hunts. (79)”

Pedantic point; Eskarina does reappear in one of the later Tiffany Aching books.