“[W]hile the Dewey system has its fine points, when you're setting out to look something up in the multidimensional folds of L-space what you really need is a ball of string.”

—Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards!

Back in my reread of Sourcery, I promised/threatened to do a deep dive into L-space when we got there. L-space, as we learn in Guards! Guards! is the warping of time and space that is caused by a critical mass of books in one place. This is a particularly acute phenomenon when the books are magical, but as we learn, all libraries (and indeed, all “poky second-hand bookshops” [230]) cause this effect, and all are thus connected in the resultant L-space.

It's impossible now, looking back over years of reading Discworld’s embarrassment of riches, to locate precisely when I went from considering the novels fun, engrossing reads to starting to think seriously about needing to do a scholarly deep dive into Sir Terry’s world-building project. When the books went from being engaging to impressing me with their philosophical depth, so cheekily disguised by their humour and frequent absurdity.

When precisely that happened, I cannot say, but I know for certain that the imagining of L-space was a profoundly significant factor.

For one thing, as a concept it pushes all my buttons: the mystical nature of libraries, the literalization of books’ capacity to shape space and time, and above all the fact that L-space comprises a labyrinth, one that deserves pride of place alongside the many labyrinths of literature, from ancient myth to those of Jorge Luis Borges, to our contemporary labyrinths of virtuality.1

That was my starting point here—a vaguely inchoate need to draw connections between L-space and all those other labyrinths and see where it led me. And as is appropriate to the topic, I meandered into some strange and wonderful places here.

1. The Magical Library

“We live for books. A sweet mission in this world dominated by disorder and decay.”

― Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Libraries are magical places. I don’t mean that figuratively; nor am I being sentimental (well, a little).

Libraries are magical because books are magical. I won’t embark here on a long discussion of magical books in fantasy and legend—spellbooks, grimoires, the Necronomicon—other than to note their ubiquity. Which shouldn’t be at all surprising, considering that magic as popularly conceived has always been closely intertwined with language, with the “magic words” of incantations that, when spoken, conjure the desired spell. This in itself should also not be surprising, considering how much of our quotidian, day-to-day life is performed through language—how much of what we do is often inextricable from what we say. If ordinary acts are effected through ordinary language, it makes sense to imagine the extraordinary will similarly be effected through extraordinary language. And that somewhere such extraordinary language is collected in a book, and that book can be found in a special library.

But then, as any avid reader knows, all books are potentially magical portals, so the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary is usually down to a given reader’s imagination. In Guards! Guards!, when we’re first introduced to L-space, Sir Terry makes this point clearly, observing that while people thought the Library at Unseen University was dangerous because of the magic books, “what made it really one of the most dangerous places there could ever be was the simple fact that it was a library” (225).

One of the organizing principles of magical humanism as I’ve conceived it is just how much of this thing we called “life” is imaginary—how much of what governs our reality comprises a set of agreed-upon fictions. Law and jurisprudence, nations and borders, currency and exchange value, social custom and conventions—the list goes on and on—all are conjured, to quote Shakespeare, “from airy nothing” and, once articulated through language, given “a local habitation and a name.”2

Is this magic? Perhaps not in the sense of Gandalf fighting the Balrog or Mickey Mouse animating a small army of mops and brooms, but I’d argue that the magic of witches and wizards and sorcerers (and sorcerers’ apprentices) as imagined in story is rooted in our most banal daily conjurations. Certain precincts of literary theory focus on performative utterances, i.e. statements that enact what they describe—apologies, for example, or promises, or when somebody says “I do” while standing before an altar. I won’t rehearse all that, other than to suggest that to some degree or another all language is performative in the way it shapes our realities. Before I’m accused of committing postmodernism, let me quote J.R.R. Tolkien’s thoughts on the matter. From his essay “On Fairy-Stories”:

[H]ow powerful, how stimulating to the very faculty that produced it, was the invention of the adjective: no spell or incantation in Faerie is more potent. And that is not surprising: such incantations might indeed be said to be only another view of adjectives, a part of speech in a mythical grammar. The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. (22)

If there’s a common thread running through both Tolkien and Sir Terry (and for what it’s worth, there are many, but bear with me here for the sake of argument), it’s this preoccupation with the transformative qualities of language and story and the capacity for narrative to shape reality.3 By extension, these repositories of language, discourse, story, and narrative comprise a labyrinth of worlds that are—to again quote Tolkien—both fair and perilous.

2. L-space

The three rules of the Librarians of Time and Space are: 1) Silence; 2) Books must be returned no later than the last date shown; 3) Do not interfere with the nature of causality.

—Guards! Guards!

As I noted in my post on Sourcery, the care with which Sir Terry crafts the Library of Unseen University, and the affection with which the Librarian is depicted, is reflective of his own attachment to the library as both physical and imaginative space. In his biography Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes, Rob Wilkins writes that as a child “Terry seems to have hung around Beaconsfield Library at the weekends in the same way other people might stand in a guitar shop on a Saturday afternoon—just to be there, in the vicinity of the thing you were passionate about, among your tribe” (46). Books for young Terry—as they were for my young self visiting the library, as they were and are for so many other passionate readers—were portals of discovery; those volumes bristling with other worlds, other lives, become in the Discworld literally alive, animated by the magic they contain. Part of the Librarian’s job is minding the more lively or obstreperous books, keeping them chained to their shelves, or, as we learn in Faust Eric (#9), keeping the racier tomes on actual ice. During a blistering heatwave in Ankh-Morpork, the Librarian keeps cool by hanging out above these latter ones:

[H]e’d rigged up a few ropes and rings in one of the sub-basements of the Unseen University library—the one where they kept the, um, erotic books. In vats of crushed ice. And he was dreamily dangling in the chilly vapour above them.

All books of magic have a life of their own. Some of the really energetic ones can’t simply be chained to the bookshelves; they have to be nailed shut or kept between steel plates. Or, in the case of the volumes on tantric sex magic for the serious connoisseur, kept under very cold water to stop from bursting into flames and scorching their severely plain covers. (5)

Magical books with a life of their own is an obvious allegory of real-world books’ volatility, and the fear they tend to inspire in people suspicious of their power (an observation made rather pointedly in Guards! Guards!, as I quote in the previous section).

L-space, we first learn in Guards! Guards!, occurs because “Books bend space and time” (230), such that a critical mass of books in one place creates a reality distortion field:

One reason the owners of those … little rambling, poky second-hand bookshops always seem slightly unearthly is that many of them really are, having strayed into this world after taking a wrong turning in their own bookshops in worlds where it is considered commendable business practice to wear carpet slippers all the time and open your shop only when you feel like it. You stray into L-space at your own peril. (230-231)

What’s more, “All libraries everywhere are connected in L-space” (231), meaning that the Librarian can traverse time and space by venturing deeper into the Library: “It seemed quite logical to the Librarian that, since there were aisles where the shelves were on the outside then there should be aisles in the space between the books themselves, created out of quantum ripples by the sheer weight of words” (230). The Librarian knows that, should he pull out a few books from a shelf and peer into the gap, “he would be peeking into different libraries under different skies.”

Libraries are all connected, as anybody first discovering the joy of inter-library loan will attest. More abstractly, libraries are connected by their common project of collecting, protecting, and sharing knowledge. This fact of their connection, of the permeability of their collections and the information gathered therein, may seem at odds with the tendency of physical libraries to often look or feel like redoubts, fortified spaces built up around their collections to protect the books within. When I did my master’s degree at the University of Toronto, the Robarts Library was somewhere I spent countless hours; approached from outside, it appears a formidable and vaguely castle-like building. Such indeed was the nature of many medieval libraries, which were often housed in monasteries—themselves fortified and built in inaccessible locations to discourage raiders. In a present moment when information is all-pervasive and inescapable, when books are cheap and plentiful (even without considering their digital versions), it can be an effort to grasp how rare and thus precious books were in the Middle Ages. The libraries guarded in fortified monasteries were like bank vaults hoarding civilizational treasure, and yet that information and knowledge still circulated, laboriously copied out in scriptoria and carried in the minds of scholars.

Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose (1980) pushes all these buttons, as it’s a murder mystery set in a medieval Italian monastery in 1327, which houses “the greatest library in Christendom” (491). The library is itself inaccessible to all but the librarian, however, as it is built as a labyrinth, which is only navigable by the librarian and his assistant. The not-at-all allusively named William of Baskerville arrives to take part in a theological debate but is asked to investigate the mysterious death of one of the monks. William frequently finds himself at odds with the librarian, the blind Jorge of Burgos—a monk whose attitude towards sharing the library’s books with his monastic brethren is, to put it mildly, pecunious.4 Monks submit a request; Jorge decides whether they are worthy of handling it. Anybody seeking to enter the library themselves risks getting lost.

The library in The Name of the Rose is thus something of an aberration—or even, perhaps, abomination, as it was specifically designed to prevent the circulation of knowledge. The villain is ultimately revealed to have murdered in order to keep secret the sole copy of a work of ancient philosophy the murderer deems too dangerous to let others see. The library’s construction as a maze is at once representative of the epistemological puzzle William of Baskerville attempts to solve, but also of containment and oblivion. Just as the classic labyrinth of myth is one in which those who enter are never meant to exit, so too is the library in The Name of the Rose a space not of circulation but where knowledge goes to die. At the end the murderer’s final act of nihilism is to set fire to the library.

The fact that both the library in The Name of the Rose and Sir Terry’s conception of L-space are labyrinths speaks to the multiplicity of that structure, both literally and metaphorically. And so I hope you’ll indulge me as we go …

3. Into the Labyrinth

“Welcome to the labyrinth, kid—only there ain't no puppets or bisexual rock stars down here.”

As I just alluded, one of the earliest, and certainly the most famous, appearances of the labyrinth in literature is the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Theseus is the son of the king of Athens, which is subject to King Minos of Crete. Every nine years as tribute Athens must send seven young men and seven young women, who will be sacrificed by being sent into the labyrinth under the palace at Knossos. The labyrinth was built by Daedalus, the master artificer, as a prison for the Minotaur. The seven and seven youths enter the labyrinth and wander, lost, until they are ultimately killed and eaten by the Minotaur.

Theseus, brave young man that he is, insists on taking the place of one of the tributes. While being feted along with his fellow Athenians the night before the sacrifice, Theseus locks eyes with Ariadne, King Minos’s daughter. Love at first sight, etc., and Ariadne surreptitiously gives Theseus a sword with which the kill the Minotaur and, more importantly, a spool of thread. She tells him to tie the thread to the labyrinth’s entrance so that he can find his way out again.

TL;DR, it all works out as planned.5 The thread Ariadne gives Theseus has become a mythic and symbolic touchstone, as has the labyrinth itself, though the latter is (as we shall see) rather more complex.

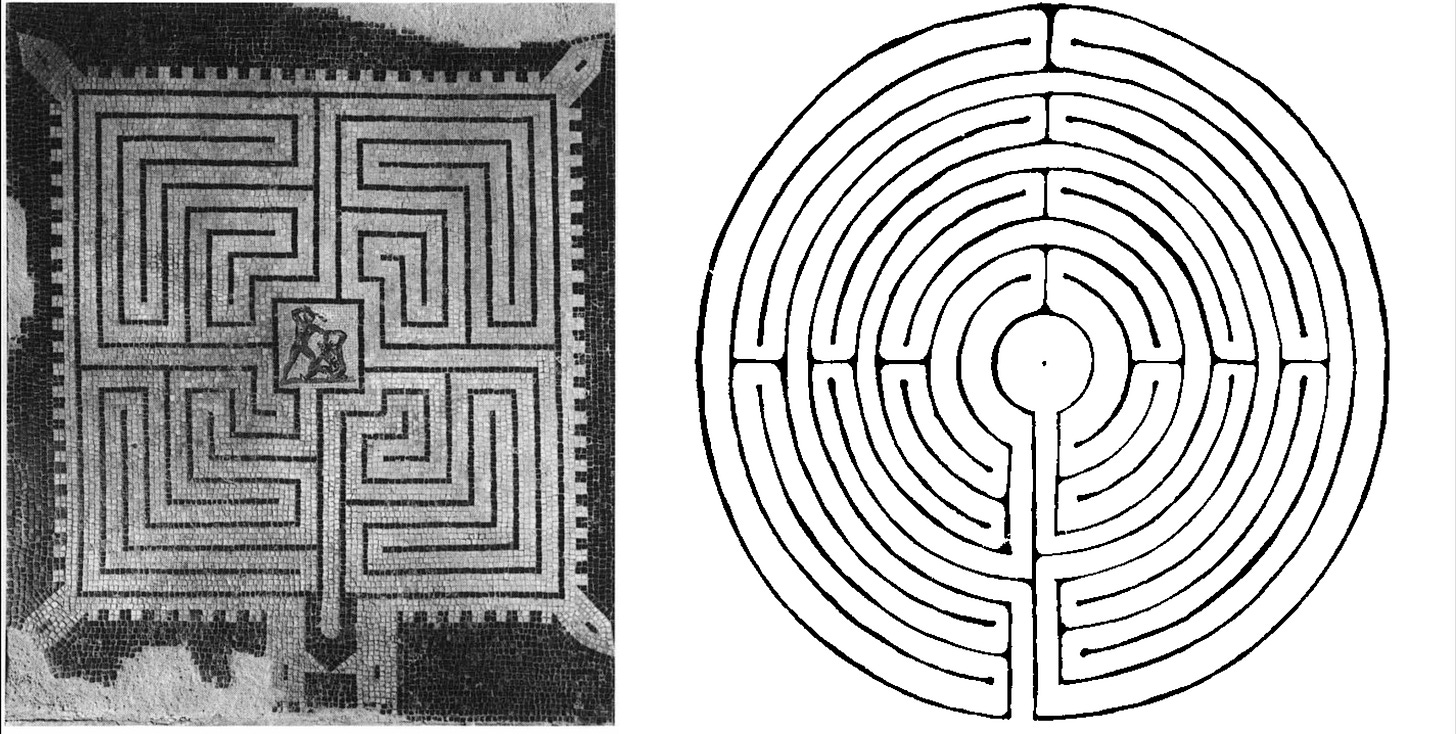

The fact that Theseus needs a thread to find his way back out of the labyrinth tells us that it is a maze, i.e. a series of corridors with many turns and forks and dead ends, designed to make those entering get lost—the kind of thing decorating the back of cereal boxes or kids’ placemats at some restaurants. It is, to use the technical term, “multicursal.” This however is at odds with depictions of the labyrinth in ancient Greek and Roman art. The “classical” labyrinth is, as Penelope Reed Doob notes in The Idea of the Labyrinth (1990), “unicursal”—a single path that winds back and forth on itself endlessly, arriving either at a central point or ultimately exiting elsewhere. Which would be tiresome and arduous to traverse, but impossible to get lost in so long as you always move forward.

Doob offers the example of a Roman mosaic from Cremona depicting Theseus slaying the Minotaur at the center of what looks like a complex maze, but which on closer examination reveals itself as one single path.

The Cremona mosaic, Doob notes, is hardly sui generis; indeed, as she observes, with vanishingly few exceptions, “all classical and medieval mazes share a remarkable characteristic: they are unicursal, with no forked paths or internal choices to be seen [her italics]” (40). This depiction of the labyrinth is puzzling, and not just because “to post-Renaissance minds a maze is either multicursal or not a maze at all” (41). The myth of Theseus itself is pretty unequivocal about the maziness of the Cretan labyrinth, “and the poetic tradition insists on [this].” And yet,

For centuries … not one visual artist seems to have drawn a labyrinth with false turnings or multiple paths even though some classical and medieval writers, and presumably some artists, knew perfectly well that there were two radically different models of the labyrinth: the multicursal labyrinth-as-building described in literature, that complex construction with many chambers and winding paths in which one can easily get lost, and the unicursal labyrinth-as-diagram in which a single twisting path laboriously meanders its way to the center and then back out. (41)

As Doob quite thoroughly explicates, very few commentators in either the classical or medieval eras take note of this discrepancy. The only two she finds who explicitly observe that the Cretan labyrinth is described differently than it is drawn are Pliny the Elder (CE 23-79) and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). Otherwise, it goes unremarked—which does not indicate indifference to this contradiction, Doob stipulates, but rather a different understanding of the labyrinth in which the unicursal and multicursal models taken together don’t comprise a contradiction but rather speak to subtler consonances.

These two paradigms of the labyrinth are symbolic in distinct ways. The unicursal labyrinth, with its winding but singular path, represents fate—the many twists and turns of one’s life leading inevitably to one place. The multicursal labyrinth by contrast is about the navigation of confusing choices and the resolution of riddles.6 The former is existential, the latter epistemological; part of Dobb’s argument, however, is that on the metaphorical level this is a distinction without a difference.7 The apparent indifference to these contradictory paradigms, she suggests, reflects a subtler understanding of the labyrinth, an understanding that doesn’t see a contradiction but rather that fate and choice coexist.

In Postscript to The Name of the Rose (1984), his commentary on his novel, Umberto Eco addresses these contrasting labyrinths by offering a third model that proves uncannily prescient for our present moment. As discussed above, the monastery’s library is a labyrinth of the multicursal variety, navigable only by the old blind monk Jorge of Burgos.

Ultimately, though he does discover the identity of the murderer, William fails in his mission. In classic murder mystery fashion, he uncovers and examines all the clues and evidence and painstakingly reconstructs the series of crimes—only to realize that he was entirely wrong, and his discovery of the guilty party was entirely accidental. In the novel’s final pages, as the Abbey burns in a fire started in the labyrinthine library, William laments to Adso,

I arrived at [the murderer]8 through an apocalyptic pattern that seemed to underlie all the crimes, and yet it was accidental. I arrived at [the murderer] seeking one criminal for all the crimes and we discovered that each crime was committed by a different person, or by no one. I arrived at [the murderer] pursuing the plan of a perverse and rational mind, and there was no plan, or, rather, [the murderer] himself was overcome by his own initial design and there began a sequence of causes, and concauses, and of causes contradicting one another, which proceeded on their own, creating relations that did not stem from any plan. Where is all my wisdom, then? I behaved stubbornly, pursuing a semblance of order, when I should have known well that there is no order in the universe. (482)

The labyrinth trodden by William and Adso—which is to say, the story in which they find themselves and not just the library—defies the two paradigms discussed here. A murder mystery, generically speaking, is a multicursal labyrinth: it is an epistemological quandary, and its pleasure lies in seeing how the detective navigates its many false turns and blind alleys. The revelation in the end, when Hercule Poirot gathers the suspects in the library and reconstructs the story, is like seeing the maze from above for the first time. At the same time, a murder mystery is also a unicursal labyrinth, insofar as the story’s narrative draws you to its narratively inevitable conclusion.9 The Name of the Rose was a favourite amongst scholars of postmodern fiction, as its resolution resists epistemological clarity. As Eco notes in Postcript, his basic story—the “whodunnit?”—isn’t a singular story, but is caught in a web of overlapping, intersecting stories. Eco states, “my basic story … ramifies into so many other stories, all stories of other conjectures, all linked with the structure of conjecture as such” (57).

A labyrinth, he continues, is an “abstract model of conjecturality,” terming our two paradigms the “classic” labyrinth versus the “mannerist” maze. But he then offers a third variety, which he identifies as “the net, or, rather, what [Gilles] Deleuze and [Felix] Guattari call ‘rhizome.’”10 The rhizome, he continues,

is so constructed that every path can be connected with every other one. It has no center, no periphery, no exit, because it is potentially infinite. The space of conjecture is rhizome space. The labyrinth of my library is a mannerist labyrinth, but the world in which William realizes he is living already has a rhizome structure: that is, it can be structured, but is never structured definitively. (57-58)

The most obvious analogue to this description is the internet: a massive morass of connections, specifically designed to be decentralized, which has no center and no periphery: wherever you find yourself is the center, and you have the capacity to connect to any other point instantaneously.11 And the internet is obviously a labyrinth in which it is as easy to get lost as the monastery’s library or Daedalus’s creation under Knossos. The fact that Eco wrote Postscript in 1983 makes this seem eerily prescient, but in fact he was walking well-trodden paths, both in terms of what had come before and what was contemporaneous. The Name of the Rose evokes numerous medieval figurations of what we today call virtual space as well as being a loving homage to the libraries and labyrinths of Jorge Luis Borges. It is also worth noting that while the internet was still over the horizon in 1983, it had already been imagined in science fiction—1983 was the year that saw the publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, the novel that set the standard for cyberpunk and popularized the concept of cyberspace.

As I’ll discuss momentarily, libraries of the present moment exist online as much as in physical spaces, but they’ve always also been spaces of virtual reality; they’ve always been labyrinths of the rhizomatic variety.

4. The Library as Labyrinth

Unseen University Library was a magical library, built on a very thin patch of space-time. There were books on distant shelves that hadn’t been written yet, books that never would be written. At least, not here. It had a circumference of a few hundred yards, but there was no known limit to its radius.

—The Last Continent (#22)

The Name of the Rose12 is a semiotic mystery, and a literary one insofar as it constitutes 500+ pages of Umberto Eco flexing his (considerable) intellectual muscles and paying homage to a host of his literary and scholarly influences. First and foremost among the novel’s many allusions (or at least the most obvious to a non-medievalist like myself) is the monastery’s librarian, the blind Jorge of Burgos—an obvious reference to the great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Borges was himself a librarian (he was named the director of Argentina’s National Public Library), and in the latter stages of his life his sight failed.

Borges was also a prolific writer of short fiction and essays on a range of themes and topics which, if you called them “eclectic” would be making a huge understatement. He frequently returned however to the twinned motifs of library and labyrinth. Most famous is his short story “The Library of Babel,” which opens with the sentence “The universe (which others call the library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries” (112). The story goes on in enumerative detail to describe the structure and layout of the library: the ventilation shaft in the middle of each chamber, one exit and entrance, four walls each with five bookshelves; each shelf’s thirty-two books of four hundred and ten pages, all identical in format.

The narrator, we gather, is one of the librarians who wander through these connected hexagonal chambers perusing the books in search of any text that is not a nonsensical jumble of letters. “I declare,” says our narrator, “that the Library is endless” (112-113), and that is the crux of the story: in the infinitude of this Library, which is “a sphere whose exact center is any hexagon and whose circumference is unattainable” [his italics] (113), and in which “there are no two identical books” (115), every single possible permutation of the alphabet is going to eventually appear, but will be so remote that the most any librarian has seen is a handful of comprehensible sentences. And yet the Library must contain:

all that is able to be expressed, in every language. All—the detailed history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalog of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogs, the proof of the falsity of those false catalogs, a proof of the falsity of the true catalog, the gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary upon that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book into every language, the interpolations of every book into all books, the treatise Bede could have written (but did not) on the mythology of the Saxon people, the lost books of Tacitus. (115)

Borges frequently played with paradox, especially the figuration of a finite space like a library or labyrinth containing the infinite. He opens his essay on Zeno’s paradox, “Avatars of the Tortoise,”13 with the observation, “There is a concept which corrupts and upsets all others. I refer not to Evil, whose limited realm is ethics; I refer to the infinite” (237).

In the context of everything I’ve been talking about here, it’s hard not to connect this corruptive quality of the infinite to the infinitude of a human mind, and its analogs in the trackless expanse of worlds to which a library grants access. In what is perhaps his most famous (or notorious) story, Borges imagines the totalizing creation of a fictional world by way of one of his other favourite motifs, the encyclopaedia. In “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” an eccentric millionaire seeks to challenge the notion of God by orchestrating the creation of an imaginary planet. Creating “a secret society of astronomers, biologists, engineers, metaphysicians, poets, chemists, algebrists, moralists, painters, geometers” (72), they collectively imagine and create a fictional planet, “with its architectures and its playing cards, the horror of its mythologies and the murmur of its tongues, its emperors and its seas, its minerals and its birds and fishes, its algebra and its fire, its theological and metaphysical controversies—all joined, articulated, coherent” (71-72). All these features of this planet—the titular Tlön—are enumerated and catalogued in a massive encyclopaedia, which wreaks havoc on the world when it is released.

Contact with the exhaustively imagined Tlön captivates humanity and causes reality to cave in: “The truth is, it wanted to cave in,” Borges’ narrator ruefully acknowledges, given our inclination to be spellbound by “any symmetry, any system with an appearance of order … How could the world not fall under the sway of Tlön, how could it not yield to the vast and minutely detailed evidence of an ordered planet?” (81) Captivated by “Tlön’s rigor,” he continues, “humanity has forgotten, and continues to forget, that it is the rigor of chess masters, not of angels.” This creation “may well be a labyrinth, but it is a labyrinth forged by men, a labyrinth destined to be deciphered by men.”

If the winding path of this essay’s particular labyrinth seems to have taken a dystopian turn, it’s worth recalling Sir Terry’s observation that what makes Unseen University’s Library a dangerous place isn’t its magic books, but the simple fact that it is a library. Borges’s dark fable in "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” as well as his concern for the corruptive influences of the infinite, find a lot of resonances in Discworld: story, narrative, and imagination are the stuff of Creation for Sir Terry, but he isn’t sentimental about it—this is, he often indicates, volatile and dangerous stuff. I haven’t yet had occasion to address Sir Terry’s only-slightly-tongue-in-cheek figuration of “the theory of narrative causality”—that will come with my (more likely more than one) post on Witches Abroad (#12)—but when I do, there’s a reasonably good chance we’ll be revisiting Borges and Tlön.

When I said at the outset that libraries are magical places, I meant magic both light and dark. As the Librarian of Unseen University knows, one enters L-space at one’s peril.

Coda: L-space Redux

“But we’re a university! We have to have a library!” said Ridcully. “It adds tone. What sort of people would we be if we didn’t go into the Library?”

“Students,” said the Senior Wrangler morosely.—The Last Continent

The Senior Wrangler’s comment is one that at once sadly resonates with me while also inspiring a modicum of guilt. I frequently craft assignments, especially for my first-year classes, that require students to go into the actual, physical library, on the closely held conviction that there is an intrinsic benefit to navigating the labyrinthine stacks and handling actual books. At the same time, I am all too cognizant of how infrequently I myself enter the library these days—how much of my research is done via online scholarly databases and the convenience of books now available in digital formats.14

The convenience, especially during these summer months when I work at home and am loath to use my campus office, much less go to the library, is seductive. It is all but frictionless. (I say this as someone who still stubbornly prefers physical books and refuses to get an e-reader, and whose personal library long ago overflowed the shelves of both my home and campus offices.) And while the convenience of a mostly-online library offers innumerable benefits, I can’t help but feel that something is lost in solely navigating the online labyrinth. What is missed is the tactility of the library itself: the smell of must and dust that is specific to books; the imposing edifice of tall shelves that remind you of how little you’ve read and how little you know; the serendipitous discovery of books and resources you were unaware of, but find because they are immediately proximate to the book you’re looking for; taking an armload of books to the nearest carrel, or perhaps just sitting down right there on the ancient carpet with the books stacked around you, eagerly rifling through their pages and making connections you had not previously imagined.

That right there? That’s the magic.

REFERENCES

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Library of Babel.” Collected Fictions. Trans Andrew Hurley. Penguin, 1998. 112-118.

---. “Avatars of the Tortoise.” Trans. James E. Irby. Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings. Eds. Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. Penguin, 1964. 237-241.

Doob, Penelope Reed. The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity Through the Middle Ages. Cornell UP, 1990.

Eco, Umberto. The Name of the Rose. Trans. William Weaver. Harcourt, 1983.

---. Postscript to The Name of the Rose. Trans William Weaver. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1984.

Pratchett, Terry. Guards! Guards! Corgi, 1989.

---. The Illustrated Eric. Illustrated by Josh Kirby. Gollancz, 1990.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-Stories.” Tree and Leaf. HarperCollins, 2001. 3-81.

NOTES

Full disclosure: I became obsessed with labyrinths from the moment I first read Borges as an undergraduate and wrote my honours thesis on the labyrinth as a trope in postmodernist fiction. Given that my supervisor was not somebody inclined to enforce brevity, I did an extremely deep dive and produced something much closer to an MA thesis—it ran to 80 pages (which were 1.5-spaced to give it the illusion of being more tightly written than it was), which really represents my first bit of genuine scholarship. Though I moved on to (many) other scholarly obsessions in the intervening thirty years (egad), I never pass up an opportunity to nerd out over labyrinths in my teaching. Or here.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Theseus’s speech in the final act. Marvelling at the story told by the lovers of their fairy-haunted night, he muses on how their fantastic tale is reminiscent of how “the lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are all of imagination compact” (5.1: 7-8). Of the poet, he says “as imagination bodies forth / The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen / Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing / A local habitation and a name” (5.1: 14-17). As it happens, this is the literal definition of poesis, which is the Greek term for the emergence of something that did not previously exist.

I originally wrote a few paragraphs here on Tolkien and “mythopoeia,” or myth-making, quoting the poem of that title he wrote to C.S. Lewis in response to Lewis’s provocative comment that myths were just “lies breathed through silver” (this was the early 1930s, and Lewis was still a militant atheist). The paragraphs were pretty good (in my opinion) but took me somewhat farther afield than I wanted. I cut them but have preserved them in a separate document for a point in the future when I inevitably return to this topic.

I had a moment of doubt in writing “pecunious,” remembering it meant miserly but unsure; so on looking it up, I found it’s one of those words than means two seemingly antithetical but actually related things. On one hand it means “Well provided with money; moneyed, wealthy” (OED), but also “miserly, ungenerous; (also) frugal, thrifty.” So this actually works well, given that as the proprietor of the “greatest library of Christendom,” Jorge oversees a collection more valuable than Smaug’s hoard, but is jealous of the books and parsimonious in sharing them.

Well, mostly. As is the way of Greek myths, we can’t have nice things. Theseus abandons Ariadne on an island on the way home to Athens (for reasons) and further forgets to fly white sails as a signal to his father than he’d succeeded. Seeing the black sails and thinking his son dead, the king throws himself off a cliff. As one does.

This element is emphasized in the film Labyrinth (1986), particularly in the scene where Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) has to resolve the classic logical conundrum of the Riddle of Two Doors.

It shouldn’t escape us, for example, that in the myth of Theseus, his confrontation with the Minotaur is inevitable no matter which kind of labyrinth he enters.

Though I’ve probably spoiled the mystery by the clues I’ve left, I’ll still leave out the name of the ultimate culprit.

And here is a moment in which I resist spiralling off into a related but digressive discussion of Sir Terry’s “theory of narrative causality.” As this essay is already too long, I’ll keep my powder dry until we get to Witches Abroad (#12).

Deleuze and Guattari expand on the metaphor of the rhizome (having introduced it in earlier works) in their book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1980). The rhizome is understood as a structure that allows connections between any of its constituent elements, a mode of thinking that resists hierarchical organization.

Depending, of course, on the quality of your connection.

I once saw Umberto Eco read from his new novel The Island of the Day Before (1994) in Toronto, and I’ll always remember the story the person introducing him told. When The Name of the Rose was initially published, the publisher planned on a small print run, expecting that this very long, very scholarly murder mystery set in the Middle Ages wouldn’t exactly set the world on fire. Eco was well enough regarded in academic circles (i.e. held in awe) that they decided to do an English translation and offered it to William Weaver. Weaver (who died in 2013 at the age of 90) was himself a well-respected translator; if you’ve read almost any Italian author of note in English, you’ll probably find Weaver’s name at the front. Weaver read The Name of the Rose, and immediately contacted the publisher, asking if he could be paid in a percentage of sales rather than the standard flat fee. The publisher thought he was getting a great deal, as the percentage of what he imagined the sales to be would have been a fraction of the regular fee.

Weaver built an addition on his house with his earnings. And he called it the “Eco Chamber.”

Again, resisting here a spiral into another Discworld connection—namely, the tortoises that appear in Pyramids (#7) and Small Gods (#13). Teppic and Ptraci’s first encounter with Ephebians occurs when they're nearly struck with arrows being shot at tortoises in the dunes outside the city as a philosopher attempts to demonstrate the literal truth of Zeno’s Paradox.

A case in point while writing this essay: for my Borges references I consulted my copy of his Collected Fictions and Selected Non-Fiction. But when tracking down his assertion of the infinite’s corruptive quality, I couldn’t initially recall which story or essay it appeared in. After a few online searches, I clarified that it was “Avatars of the Tortoise,” an essay that was inconveniently not selected for the non-fiction volume in my hand. A few more searches told me it was in the book Labyrinths, a worn copy of which I have in my campus office. Loath however to make to (admittedly short) trek to the university, I instead found a facsimile of the PDF online … which then joined the ever-growing folder on my computer desktop titled “Books in PDF.”

An absolute pleasure to read, thank you!

A nit: _Neuromancer_ was published in 1984, not 1983.

However, the Internet was certainly part of SF thought before then. There were many fictional representations, e.g. "True Names" (1981), _Web of Angels_ (1980), _The Shockwave Rider_ (1975) -- "A Logic Named Joe" (1946) is often cited as the first representation of general network access. There were also fans who experienced the net, as many of them had access to the ARPAnet (founded in 1969) or the early Usenet (established in 1980). Yes, this access was mostly restricted to computer people (although IIRC Usenet had a lot of college students not majoring in computers); however, a survey at the 1979 Disclave (a late lamented SF convention not noted for nerdiness), intended to show that the convention had all the talents needed for a habitat, found something like a quarter of the attendees worked with computers. (Ancient recollection -- the number might have been higher.

That's a wonderful anecdote about the translater of _The Name of the Rose_.