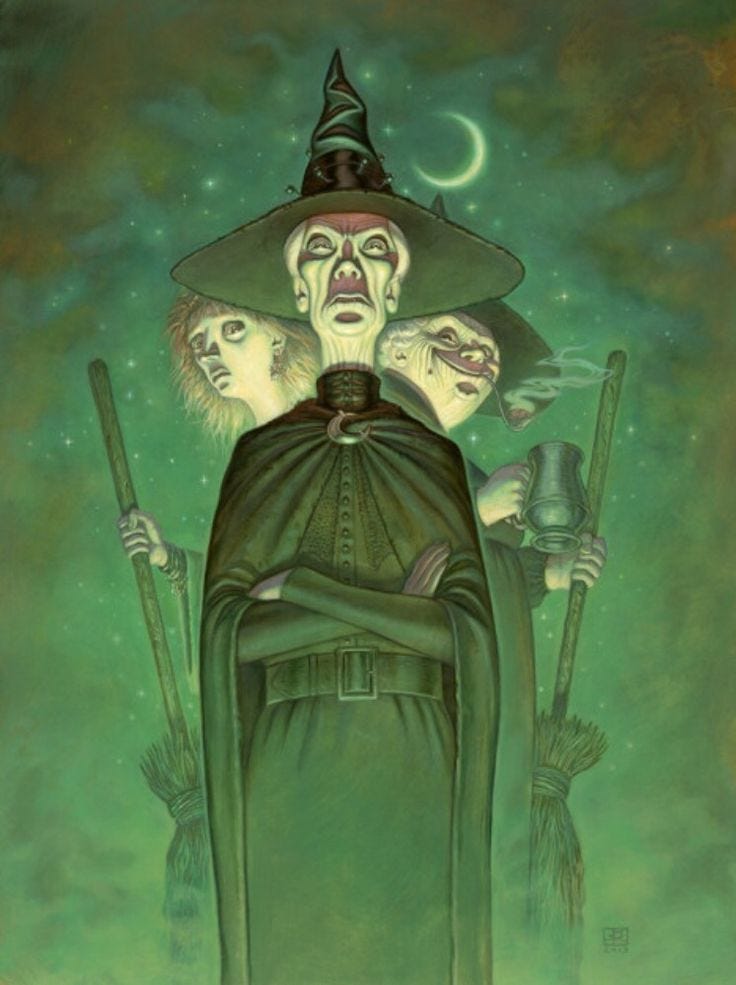

Three witches. A Fool. A murdered king. A usurper and his scheming wife. A mountainous, thickly forested kingdom. A ghost haunting the castle’s drafty corridors. A storm that provides convenient pathetic fallacy.

Is this all sounding familiar? But wait, there’s more! A company of traveling players. A brilliant Dwarf playwright who is literally assaulted by inspiration at all hours. A foundling child, heir to the throne, rescued by the witches and raised by the theatre troupe. A kingdom’s crown, lost but possibly languishing in the costume cart. Lots of plays—comedies, tragedies, a bit with a dog—most of which are vaguely reminiscent of something you might have seen or read. A possible love subplot between a witch and a fool.

Power. Political power of the monarchical variety. Magical power of the witchy variety. The power of family. The power of story and the spoken word to change hearts and change the world.

Or, more prosaically: King Verence of Lancre, a decent enough king—pretty good, knows the assignment—is murdered by his cousin Duke Felmet at the behest of Felmet’s ambitious wife. Before the self-styled power couple can clean up their loose ends, a loyal servant escapes with the King’s infant heir and the ancestral crown of Lancre. In his last act, dying from a crossbow bolt between the shoulder blades, he hands the child to the three witches. Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, and Magrat Garlick give the baby to a husband and wife who run a traveling band of players, who promise to raise him as their own. The crown finds its way into a box among the props.

Time passes. Felmet cannot be comfortable on his new throne, especially not with that annoying blood on his hands that just won’t wash off, no matter how many times he scrubs with a steel file. He begins to suspect that the witches have cursed him. Are cursing him. And oversalting his food. The witches, meanwhile, while confident that the heir to the throne will return to reclaim his rightful place, grow concerned because the land itself is responding badly to having an illegitimate king. Well, actually, it doesn’t care so much about illegitimacy—it’s the fact that the king hates his kingdom that’s causing issues. The witches decide to speed things up by magically freezing Lancre in time for fifteen years to let the oblivious heir reach throne-appropriate age.

The heir in question, meanwhile, accidentally named Tomjohn by his adopted parents, grows into a fantastically talented actor. Hwel the Dwarf, the company’s prodigious playwright, marvels at how the words he writes are given life by Tomjohn’s performances.

And then Felmet has a plan: the play’s the thing, to cement the narrative of his rightful ascent and vilify the witches, and sends his trusty Fool—who, weirdly, bears a striking resemblance to Tomjohn—to hire the traveling players to come to Lancre and perform a story to his specifications.

What could possibly go wrong?

1. All the world’s a stage, a poor player signifying the play’s the thing

Wyrd Sisters (1988) is the sixth Discworld novel and the one I most frequently recommend as a good starting point. I was curious whether, on rereading it, I would change my mind on that point. Turns out it’s just the opposite: my appreciation for this first appearance of the three witches has only deepened. There’s a number of reasons for this, which I’ll try to tease out as I go. One big one, however, is that Sir Terry’s use of a Shakespearean framework, for all its little in-jokes and easter eggs and allusions, doesn’t merely hang the story on the edifice of Macbeth. The Scottish Play is its starting point, literally: we begin in precisely the same place, with a trio of witches around a cauldron as lightning stabs the sky. The murder of a king, the blood that won’t wash off, a ghost as a guilty conscience, a spectral dagger … but there’s also what I suppose we might call a meta-Shakespearean dimension to the story, as the traveling company of players and their in-house Shakespeare analogue Hwel provide a constant reflection on the principle that All The World’s A Stage.

Meta-Shakespeare arguably comprises its own subgenre, ranging from such plays as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard and Goodnight Desdemona, Good Morning Juliet by Ann-Marie MacDonald to films like Shakespeare in Love (1998) and All is True (2018), to novels like John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius (2000) and The Daughter of Time (1951) by Josephine Tey. And of course, Wyrd Sisters.

A bit later in this essay I get into questions of the overlap between mythology, archetype, and cliché, and the ways in those are all just examples of overdetermined language and story. Shakespeare comprises his own mythology; a first-time reader of Hamlet might be surprised at the critical mass of well-worn clichés its characters spout.1 In our first video for The Magical Humanist, I likened the question of whether J.R.R. Tolkien invented fantasy to whether William Shakespeare “invented” Romeo and Juliet. TL;DR: no. Like everything he wrote, Shakespeare cribbed Romeo and Juliet from extant sources, but we now indelibly associate the story and characters with him.

Hence, when we get meta with Shakespeare, we’re effectively deconstructing and/or interrogating a form of mythology that is rooted, as is genre more generally, in expectations born of repetition. We don’t go see Romeo and Juliet in the hopes that maybe this time Romeo will receive the Friar’s letter about Juliet faking her death; we don’t wonder if, in this production, Macbeth will dismiss the witches’ prophecy and return to Glamis with divorce papers in hand. “Audiences know what to expect,” says the Player in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, “and that is all that they are prepared to believe in.”

That sort of expectation holds its own magic, which is what Sir Terry engages with in Wyrd Sisters. Much of the larger project of Discworld is to one degree or another preoccupied with taking the piss of such expectations: challenging the conventions of genre and by extension the sense of inevitability baked into mythologies ancient and modern. Macbeth is in this respect the perfect vehicle as it offers not just a set of overdetermined Shakespearean conventions, but it is a play specifically about fate.

Also, witches.

I don’t often have the chance to nerd out about Shakespeare, so I beg your indulgence. Though my own scholarship is contemporary, focusing mostly on post-WWII American literature, film, and popular culture, as well as SFF and various other brands of speculative fiction, there was a time when I considered being a Shakespearean. A bad experience in writing what ended up being an ill-considered and overly long paper on Julius Caesar for my masters degree dissuaded me; but I still gravitated to Shakespeare in the theatre and always leapt at the chance to act in different productions. I never had major roles, mainly because I’m not a very good actor. I only realized this sad fact when I started directing plays—which, as it turned out, I am quite good at, but from that perspective I realized immediately what my actorly shortcomings were.

I directed two Shakespeares during my PhD: Richard III, which still counts as one of my life’s proudest and most rewarding experiences; and Macbeth, about 90% of which was a proud and rewarding experience.2

And I’ve always loved teaching the occasional Shakespeare when I’ve had the chance. For these reasons, Sir Terry’s Shakespearean treatments (Lords and Ladies [#14], also a witches novel, is the other one) are kind of a sweet spot for me: fantasy? Shakespeare? sharp critical commentary by way of sharp critical comedy? Sign me up.3

Macbeth was the first Shakespeare I read in which I truly got it for the first time. I have to imagine that the other plays I’d done had familiarized me enough with Shakespeare’s language to get me to a place where I was ready—loosened the jar enough, you could say. That coupled with the fact that the Scottish Play is one of the leaner and more fast-paced stories meant I read it in one sitting. I was enthralled. Not only was it a great potboiler, but it had that whole supernatural dimension to it.

Sir Terry doesn’t limit himself to Macbeth: the frequent references to Hwel’s back-catalogue and the various productions the company stages function like a grab-bag of allusive easter eggs pulled from the First Folio. Nor is Hwel solely a Shakespearean dwarf, as at one point we see him struggling to figure out how to manage a falling chandelier as he drafts a play about a deformed hero in a half-mask. As the company travels to Lancre for their performance and Hwel feverishly rewrites the Macbeth analogue commissioned by Felmet, Tomjohn reads a few of the discarded pages and keeps “one of the strangest” (255):

1ST WITCH: He’s late.

(Pause)

2ND WITCH: He said he would come.

(Pause)

3RD WITCH: He said he would come but he hasn’t. This is my last newt. I saved it for him. And he hasn’t come.

(Pause)

(In truth, I would pay good money to see a Godot/Macbeth mash-up in which the witches merely mope about the cauldron and speak in cryptic fragments for two hours and Macbeth never appears.)

When the troupe finally makes it to Lancre and the play is performed, Granny Weatherwax experiences an unaccustomed discomfort in the presence of magic that is beyond her grasp:

The theatre worried her. It had a magic of its own, one that didn’t belong to her, one that wasn’t in her control. It changed the world, and said things that were otherwise than they were. And it was worse than that. It was magic that didn’t belong to magical people. It was commanded by ordinary people, who didn’t know the rules. They altered the world because it sounded better. (276)

Death himself, who is loitering around backstage for reasons that become apparent soon enough, has a similar thought as he looks at the costume racks and prop tables: “There was something here, he thought, that nearly belonged to the gods. Humans had built a world inside the world, which reflected it in pretty much the same way as a drop of water reflects the landscape” (297). Granny and the others watch as the three witches in the play are vilified and depicted as evil: “This is Art holding a Mirror up to Life,” Granny thinks, “That’s why everything is exactly the wrong way round” (283).

There’s a lot to unpack in these sequences, not least of which is the fact that Shakespeare included the witches in Macbeth in part for the benefit of the recently crowned James I, who had written a book about witchcraft. The reference to art as a mirror of nature quotes Hamlet (III.ii: 23-24)—though Granny’s (and Death’s) observation about the mirror’s distorting nature rather than its transparent faithfulness is more aligned with Oscar Wilde’s disdain for people who “quote that hackneyed passage about Art holding the mirror up to Nature,” who don’t grasp “that this unfortunate aphorism is deliberately said by Hamlet in order to convince the bystanders of his absolute insanity in all art-matters” (30)

The magic of theatre is the magic of story, but also of illusion: anybody who has been involved in theatre or who has seen plays is aware of the often bizarre alchemy that occurs in that space. Whether the costumes and sets are scrupulously realistic or merely hinted at, whether it’s a lavish professional production or a shoestring student show, it can attain a magic that, as death observes, “nearly belong[s] to the gods.”

2. The charm’s wound up

If you were looking for a scene in Discworld that epitomizes Sir Terry’s particular style and sensibility, you could do worse than the opening of Wyrd Sisters:

The wind howled. Lightning stabbed at the earth erratically, like an inefficient assassin. Thunder rolled back and forth across the dark, rain-lashed hills.

The night was as black as the inside of a cat. It was the kind of night, you could believe, on which gods moved men as though they were pawns on the chessboard of fate. In the middle of this elemental storm a fire gleamed among the dripping furze bushes like the madness in a weasel's eye. It illuminated three hunched figures. As the cauldron bubbled an eldritch voice shrieked: “When shall we three meet again?”

There was a pause.

Finally another voice said, in far more ordinary tones: “Well, I can do next Tuesday.” (5)

This is our introduction to the three witches. Granny Weatherwax we’ve already met in Equal Rites (#3); here with her are Nanny Ogg and Magrat Garlick. Nanny Ogg appears as the antithesis of Granny’s haughty, austere severity: ribald and cheerfully uncouth, she loves a drink, sings a wide selection of bawdy and indeed borderline obscene songs,4 and lives in the center of town at the center of a huge extended family in flagrant disregard of the convention that witches should live alone and apart. Magrat, the youngest of the trio, is a newly minted witch; she is nervous about her place but keen to introduce what we recognize as a certain New Age spiritual sensibility. For all that, Magrat has game: she’s a pretty good witch, though she self-sabotages more often than not through her own sense of insecurity.

(And I’ll say this once: should a witches film ever be made, the perfect casting is Maggie Smith as Granny Weatherwax, Miriam Margolyes as Nanny Ogg, and Phoebe Waller-Bridge as Magrat Garlick.

Come at me. This is a hill I will die on.)

As with the previous Discworld novels5 (and many to come), Wyrd Sisters is preoccupied with magic: its nature and use, its relationship to power, and its function as power. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Wyrd Sisters picks up a handful of threads from Equal Rites’ consideration of male vs. female, wizard vs. witch magic—and Sourcery, as we recently revisited, is a novel preoccupied with wizards.

Equal Rites introduced us to the witch as village sage, healer, midwife, and general counsellor—capable of magic but more inclined, in Granny Weatherwax’s example, to practice “headology.” Much to her apprentice’s frustration, headology is as much about not doing magic as anything, relying on knowledge of people and doing the most by meddling the least. That principle of not meddling is central to Granny’s ethos in Wyrd Sisters: though she and her fellow witches are well aware of Felmet’s regicide and the illegitimacy of his rule, to say nothing of knowing the rightful king is alive and well, Granny insists it behoves them to let things take their course. It is not for the witches to meddle in the affairs of state, especially not with magic. “Magic is to be ruled,” Granny says, “not for ruling” (156).

Well … it is not for them to meddle, until it is. Granny eventually reverses her stance, when it becomes clear that the kingdom itself demands it. Felmet’s usurpation offends the natural order, though not for the same reasons one finds in Macbeth or other such instances in Shakespeare.

The natural world revolting at human transgression, especially regicide, is a familiar conceit in Shakespeare. The conspiracy to assassinate Julius Caesar6 prompts such a perturbation of the heavens that even the usually sardonic Casca is terrified: “Are you not moved,” he asks Cicero, “when all the sway of earth / Shakes like a thing unfirm?” (I.iii: 3-4) So terrible is the “tempest dropping fire” that he declares “Either there is a civil strife in heaven, / Or else the world, too saucy with the gods, / Incenses them to send destruction” (I.iii: 11-13). King Lear famously rages against a storm brought both by his daughters’ betrayal of him and his own rejection of his faithful daughter Cordelia. And of course, the morning after Duncan’s murder at Macbeth’s hands, the younger lord Lennox describes the storm of previous before, whose violence edged into the uncanny:

The night has been unruly: where we lay,

Our chimneys were blown down; and, as they say,

Lamentings heard i' the air; strange screams of death,

And prophesying with accents terrible

Of dire combustion and confused events

New hatch'd to the woeful time: the obscure bird

Clamour'd the livelong night: some say, the earth

Was feverous and did shake. (II.iii: 50-57)

Shakespeare had one foot in the medieval and one in modernity. His plays, especially his history plays, are profoundly nuanced considerations of power and politics,7 while still being invested in the supernatural dimension of divine right. Regicide is the most unnatural of crimes, as is comprises the murder of God’s anointed—hence the revolt of nature.8

In Wyrd Sisters, Granny Weatherwax senses that something is off. The kingdom—the land itself—is unhappy. Not because it lacks a rightful king, but because the king who took the throne hates the land. Felmet murdered King Verence, but this in itself doesn’t perturb Granny; that’s just the sort of things kings do, it’s practically part of the job description. The problem with Felmet, as far as Lancre is concerned, is the contempt with which he regards the narrow strip of mountainous, forested land over which he reigns. As Granny puts it as she enumerates the reasons why now is the time to meddle, “One, kings go round killing each other because it’s all part of destiny and such and doesn’t count as murder, and two, they killed for the kingdom. That’s the important bit. But this new man just wants the power. He hates the kingdom” (120).

There’s a productive tension baked into Discworld, between the generic conventions of fantasy—the medieval sensibility of an extrinsic order such as manifested in fate and prophecy and the trope of the “true” king or Chosen One—and Sir Terry’s secular humanist, democratic sensibilities. Wyrd Sisters is exemplary of this tension and the way he’s starting to work through it. He hangs the novel’s premise in part on Macbeth, but doesn’t leave the play’s understanding of divine right intact. Divine right is an extrinsic principle, which is to say, it’s imposed from without by God or gods; by contrast, Lancre’s complaint comes literally from the ground up—grass roots, as it were, if there is grass to be found among the forests and crags. But not solely from the land: “A kingdom is made up of all sorts of things,” says Granny.

Ideas. Loyalties. Memories. It all sort of exists together. And then all these things create some kind of life. Not a body kind of life, more like a living idea. Made up of everything that’s alive and what they’re thinking. And what the people before them thought. (119-120)

What Granny Weatherwax here describes is an understanding of nation as idea rather than an innate thing. The king is not divinely connected to the land, but is a part of this larger interdependent network of ideas, loyalties, and memories identified by Granny; hence, the lineage of the monarch is less important than the monarch’s investment in the kingdom. In future witches novels, Lancre becomes refined into a sort of de facto democratic society over which the king reigns by the people’s sufferance largely because the people assume a king is needed. This sensibility starts to emerge in Wyrd Sisters, and culminates in the fact that the “rightful” king, Tomjohn, whom even the witches assume with claim the crown, rejects this putative destiny. Instead, the Fool in the end ascends to the throne—who, Granny declares to the people of Lancre, is the late king’s son by another woman. But as she reveals later to Magrat and Nanny Ogg, both the Fool (crowned Verence II) and Tomjohn, are actually the children of the former fool with the late queen.

So much for destiny.

3. Wyrd Fiction

But, speaking of destiny …

In some ways, Wyrd Sisters is to Macbeth as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead9 is to Hamlet. Except not really. The common element they share is in shifting the perspective of a familiar Shakespearean play to minor or peripheral characters. We never really ask ourselves about what the witches do when they’re not waylaying random Scottish lords with cryptic prophecies. Are they friends, or just work associates? Is this their primary profession, or just a hobby? Do they repair to the pub after their little performances to give each other notes?

In Macbeth the witches are principally plot devices, as indicated by their identification as the “weird sisters,” which signals that they’re agents of fate. Significantly, they are only called witches in the play’s paratextual designations as “First Witch,” “Second Witch,” “Third Witch”—otherwise they are the “weird sisters” or “weird women.” As I’ve discussed in a previous essay,10 our contemporary colloquial understanding of “weird” as odd, strange, or unusual only becomes commonplace in the 19th century. Prior to that it was associated with the supernatural, specifically in reference to fate and destiny. Its earliest use was not adjective but noun, literally meaning “fate.”11 The spelling wyrd is the Old English, which in Shakespeare’s First Folio (our sole source for Macbeth) is variously spelled weyard or weyward. The meaning, however, remains the same: the witches are prophetic agents of the supernatural … but to what end? They are obnoxiously vague and cryptic about their intentions, if not their actual prophecies.

If you’ve read Macbeth for an English class in high school or university, you’ve almost certainly addressed one of the questions perennially asked about the witches: are they straight-up oracles of destiny, or do their prophecies actively shape events? To put it another way: would Macbeth and his Lady have embarked on their murderous ascent to the throne if not for the promise embedded in the weird sisters’ prophecy? Would he have still become king had he done nothing?

We can’t answer these questions, of course, because we have no insight into the witches’ motives—no scene prefacing the play in which they hatch a plan to take revenge on both King Duncan and Macbeth (for reasons) and paving the way for that nice boy Malcolm to become king. We can be just like that bloke, wossname, Iago. No: the question of fate vs. free will is necessarily unanswerable, and the witches play the overdetermined archetypal role of both the three Fates and the Triple Goddess. Sir Terry leans into the latter by explicitly shaping Granny, Nanny, and Magrat as Crone, Mother, and Maiden respectively.12

As I’ve said before in this series, and will certainly say again, many of the characters and circumstances in Discworld begin in cliché: the fearsome witch in the tall hat, the haughty bearded wizard, the excessively muscled loincloth-clad barbarian, the sentient sword of destiny; Death himself is a cowled skeleton with a scythe who rides a pale horse; the list of examples could go on at some length, but the point is that “cliché” shares territory with such other terms as “overdetermined” and “archetype.” The term in semiotics is “overcoded,” which refers to the way in which frequent use of a word or concept leads to its meaning being intuitively understood—and as a result, largely uninterrogated and taken as given.13

Fate and destiny—the unanswered but central question of Macbeth—are in Sir Terry’s hands not an extrinsic organizing principle, but the sum of contingent forces that come to resemble something like inevitability. Which may seem a distinction without a difference (fate and destiny are, by definition, inevitable), but they are not the same thing. Clichés and archetypes alike are the product of repetition; stories told over and over in the same way—genre, in other words—arrive ultimately at a set of expectations that feel inevitable. Or to put it another way: narrative left unchecked becomes destiny.14

Fate in this understanding is itself a product of overdetermination.

The witches in Macbeth don’t need inner lives because, as I already noted, they’re plot devices who derive symbolic power from myth and legend. They are, for all intents and purposes, archetypes.15 Granny, Nanny, and Magrat are something at once greater and lesser than archetypal. Lesser because they’re demystified, rendered as fallible human characters; greater for precisely the same reason. They are not agents of fate but live inside it. With Wyrd Sisters, it’s as if Sir Terry has popped the hood to give us a glimpse of the workings within.

REFERENCES

Pratchett, Terry. Witches Abroad. Corgi, 1991.

---. Wyrd Sisters. Corgi, 1988.

Shakspeare, William. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. https://shakespeare.mit.edu/

Snyder, Timothy. The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. Random House, 2018.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Decay of Lying.” Intentions. Brentano’s, 1905. 1-56.

NOTES

As my previous posts were on 28 Years Later, I can’t help but point out Dr. Kelson’s little Hamlet shout-out. Holding the newly scoured skull of the unfortunate Swedish soldier who was decapitated in grotesque fashion, Kelson murmurs wryly, “Alas, poor Erik.” The moment is particularly funny for being spoken by Ralph Fiennes, who is not only one of the great Shakespearean actors of his generation, but was one of the great Hamlets.

The curse is real. That’s all I’ll say about that.

Keeping with the post-apocalyptic vibe of my last two posts, one of my favourite novels to teach is Station Eleven (2014) by Emily St. John Mandel. It begins at a performance of King Lear at the Elgin Theatre in Toronto in which the actor playing Lear dies of a heart attack on stage. That night is also when a virulent and lethal flu strain hits North America as it wipes out 99% of the world’s population. Twenty years later, one of the child actors who’d been onstage that night is now an actor with the Traveling Symphony, a troupe of musicians and actors who do a circuit of the settlements around the Great Lakes region of the U.S., performing Shakespeare and classical music. Unlike many post-apocalyptic narratives, which focus primarily on the how of survival, Station Eleven addresses the why—why survive? what makes life worth living? what nourishes the soul? When I finally watched the HBO miniseries adapting the novel, I wrote at some length about it over on Medium. It’s really only a matter of time before I revisit the novel here, probably the next time I teach it.

The two we most often hear snippets of are “The Hedgehog Can Never Be Buggered At All” and “The Wizard’s Staff has a Knob on the End.” Terry Pratchett fans being the breed they are, both songs have been written in lengthy entirety and put to music. “Hedgehog” is here, and “Wizard” is here. Enjoy, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

In varying degrees of focus and seriousness, of course.

Technically not a king, and Rome at the time of his assassination was still a republic. Hence the rationale for his assassination—the fear that he was about to crown himself. But Caesar was a figure of great fascination to Elizabethan audiences for precisely the reason that, to their mind, monarchy was the obvious and proper form of government, and so the actions of the conspirators were at best wrong-headed. In this logic, Caesar should have been king, and so the conspirators’ plot has much the same effect as Duncan’s murder.

At some point down the line I plan on writing something substantial on A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones, specifically in terms of the contradiction I see at the center of George R.R. Martin’s world-building. On one hand, he offers a classic Manichaean fantasy framework—Light v. Dark, prophecy, Chosen One, etc. On the other, what sets ASOIAF apart (and what made GoT a good fit on HBO alongside The Sopranos and The Wire) is the granular power dynamics governing his world, in which “divine right” belongs to whoever can claim the Iron Throne by whatever means are available. I bring this up here because the “game” of thrones precipitating the action was loosely based on England’s Wars of the Roses, which was depicted by Shakespeare in Henry VI parts 1-3, and culminating in Richard III. GRRM himself points to the consonance between the historical warring houses of York and Lancaster and Westeros’s Starks and Lannisters.

Resisting the urge to go down this particular rabbit hole as it occurs to me that Shakespeare reserves the most supernatural and mythic characterization of divine right for his tragedies, but generally eschews it in the histories.

The second play I directed! Also one of my proudest moments. My dissertation’s second reader, who is one of my favourite people in the world, came to the opening night performance. At the pub afterward she bought me a beer and handed me a card she’d written in the moments after curtain call, praising the production and ending with the admonition “AND NOW KINDLY WRITE YOUR FUCKING THESIS ❤️.” Because, yes, the four plays I directed during my PhD were elaborate procrastination techniques. About which, I should say, I have zero regrets. (I will revisit the topic of beneficial digression at some point in the future when I write an essay on the value of lengthy footnotes, something the Discworld novels employ to great effect).

“The Trumpian Weird.” If you haven’t read it you should check it out! It remains one of my favourite essays on The Magical Humanist so far, and I really get into the weeds on the meaning and etymology of “weird.” If that’s your sort of thing. Weirdo.

One of the references in the Oxford English Dictionary quotes Beowulf: the titular character says "gaéð á wyrd swá hío scel,” which translates to “Fate shall go as she will.”

A handful of productions of Macbeth I’ve seen have gone with the Triple Goddess casting; some (like the not-great Polanski movie) are faithful to the text’s description of all three of them as hideous hags; but most frequent in my experience is the tendency toward what might charitably be called Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Witches.

I talk about this at some greater length in the second instalment of my series on the Relative Weird.

A couple of points to make here: first, this is a theme to which Sir Terry returns in a big way in the next witches novel, Witches Abroad (#12). A teaser: “It is now impossible for the third and youngest son of any king, if he should embark on a quest which has so far claimed his older brothers, not to succeed” (13). Witches Abroad is my standard go-to Pratchett to teach whenever I have the opportunity to teach a fantasy class, specifically because it is all about “the theory of narrative causality” as Sir Terry dubs this storytelling/genre tendency. It’s been interesting on rereading Wyrd Sisters—which I haven’t done since teaching Witches Abroad a variety of times—to see these themes getting a test drive here.

Second, I can’t think about these issues without also linking them to the deleterious effects of political mythologizing. Historian Timothy Snyder, who has accrued a certain celebrity these past few years with his short book On Tyranny (2017), identifies part of our current malaise as proceeding from what he calls “the politics of inevitability.” In The Road to Unfreedom (2018), he identifies this as “a sense that the future is just more of the present, that the laws of progress are known, that there are no alternatives, and therefore nothing really to be done” (7). The politics of inevitability arguably informs a critical mass of our apocalyptic ideation in popular culture, with large-scale collapse and destruction variously figured as unavoidable or the only possible way to bring about change. The observation that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism is a sentiment that has been expressed by a ranger of thinkers from Fredric Jameson to Slavoj Žižek. (This is also a subject I touch on in my previous two essays on 28 Years Later).

I add the qualifier “for all intents and purposes” because I don’t really want to get into the weeds on what qualifies as an “archetype”—which means different things (or varying degrees of the same thing) depending on whether you’re hewing to the strict definition as laid out by Carl Gustav Jung, applying it in the broader literary sense such as advanced by Northrop Frye in Anatomy of Criticism (1957), or in the loosest colloquial sense. My own usage here falls somewhere between the latter two.

Oh, I’d never thought of Phoebe Waller-Bridge as Magrat, that’s brilliant! But surely Ben Elton’s sitcom ‘Upstart Crow’ deserves mention among the meta-Shakespeares?

Great stuff as ever. I like that it’s your usual recommendation for an intro to Discworld. Quite by chance, it was mine. Stop me if you’ve heard this story before (I did a Post about it a while back). Years ago I was working as a porter in a University library and while collecting books one morning came across a copy (hardback with the original Josh Kirby cover, as per the first image in your post). I put it in the lost property box and when it was unclaimed at the end of the term I snaffled it. I can’t remember the exact date but certainly not many years after first publication.

I was hooked and have been ever since.